World Stamps

Poland and Vatican City stamps feature the Black Madonna: Stamps of Eastern Europe

By Rick Miller

For Christians worldwide, Mary, a Jewish girl from the tribe of Judah who lived more than 2,000 years ago, stands near the center of Christian belief.

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke tell how, while yet a virgin, she conceived a child by the power of the Holy Ghost. Christians believe that child, Jesus, was the incarnate son of God and God incarnate, whose sacrificial death and Resurrection is the central tenet of Christianity.

Perhaps not surprisingly, views of Mary within the different branches of Christianity, vary widely. The veneration of Mary is strongest in Roman Catholicism, which offers the doctrines of the Immaculate Conception, Perpetual Virginity, and the Bodily Assumption of Mary.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

The Immaculate Conception is the doctrine that Mary, alone of all the human race, was conceived without the taint of original sin. The Bodily Assumption of Mary holds that she did not die, but was assumed bodily into heaven at the end of her life on earth.

In Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Christianity, Mary has the title Theotokos, meaning God-Bearer. Orthodox Christianity emphasizes the divine holiness of Mary and her role as a mediator of God’s grace.

Protestant Christians generally have a less mystical and less exalted view of Mary. While most accept her title as Mother of God, they cannot be said to venerate Mary in the same way as Roman Catholics and Orthodox Christians do.

While Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians offer prayer to and through the Virgin Mary, Protestants generally do not.

Over the centuries, Mary has been the subject of more Christian art than any other person, with the possible exception of Jesus.

Paintings, icons, and statues of Mary range from the catacombs of Rome to the art galleries of modern glittering cities. Most artists have tended to show Mary as looking very much like themselves. The Black Madonnas of Europe are an exception.

Some European Black Madonnas were created intentionally, but many have turned black over the centuries due to chemical reactions of the paint to environmental contaminants and smoke from votive candles.

For some, Black Madonnas symbolize a link with nature and a reference to the earth-mother goddesses of pagan religion. For others, they symbolize transformation, inspiration, and spiritual awakening of the believer. Some Black Madonnas are associated with miracles, and a few are the objects of Christian pilgrimage.

France boasts the most Black Madonnas, with 39 recognized by church authorities.

Recognized Black Madonnas in Eastern Europe include those at Bistrica, Croatia; Brno, Czech Republic; Prague, Czech Republic; Vitina-Letnica, Kosovo; Vilnius, Lithuania; Kalista, Macedonia; Ohrid, Macedonia; Kostroma, Russia; Apatin, Serbia; Koprivna, Slovenia; and Hoshiv, Ukraine.

Several Eastern European Black Madonnas have been commemorated on stamps.

Probably the most famous Black Madonna of Eastern Europe is Poland’s Black Madonna of Czestochowa, also known as the Black Madonna of Jasna Gora.

The icon is seen on the Poland 65-zloty stamp (Scott 2529) shown nearby. The stamp, printed by photogravure, is perforated gauge 11.

A two-stamp souvenir sheet of Scott 2529 is also noted and valued but not listed in the 2016 Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue. The stamp and souvenir sheet were issued Aug. 26, 1982, for the 600th anniversary of the arrival of the icon at Jasna Gora.

Also shown in the first illustration (right) is a Poland 1.10z Black Madonna of Jasna Gora stamp (Scott 3521), which was part of a three-stamp set issued May 9, 2000, for the 80th birthday of Pope John Paul II, who was canonized a saint by Pope Francis April 27, 2014. The engraved and lithographed stamp is perforated gauge 12¾. The stamp design is by famed Polish engraver Czeslaw Slania.

This Black Madonna icon is housed in the Jasna Gora monastery in Czestochowa, Poland. The origins of the icon are shrouded in mystery and legend.

Most scholars agree that it is Byzantine in origin and dates to the sixth to ninth centuries. It likely sojourned in Hungary and Ukraine for a time before being brought to its present location during the time of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Icons are more than just paintings to be appreciated for their artistic merits. The Orthodox Christian artists who compose them use visual symbology to convey religious and mystical concepts to the viewer. This was particularly important in pre-literate societies.

The Black Madonna of Jasna Gora shows the Virgin as Hodegetria (she who shows the way). In this familiar compositional arrangement, the Virgin uses her right hand to direct attention away from herself and toward the Christ Child, the source of salvation. Jesus holds a book of Gospels in his left hand and raises his right hand toward the viewer in blessing.

The icon was brought to the monastery by Prince Wladyslaw Opolczyk in 1384. In 1655, 70 monks and 180 noblemen in the Monastery of Jasna Gora withstood a 40-day siege by 4,000 Swedish soldiers during the Second Northern War.

The unlikely victory was a turning point in the war and was largely credited to the intervention of the Holy Virgin. This led King John II Casimir Vasa to proclaim the icon as the queen and protectoress of Poland.

On Sept. 8, 1717, Pope Clement XI issued a canonical coronation to the icon as queen and protectoress of Poland.

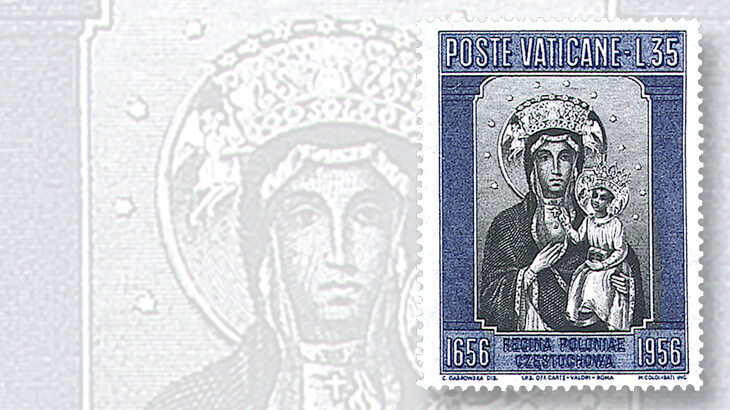

In 1956, Vatican City issued a set of three stamps commemorating the 300th anniversary of the icon’s canonical coronation (Scott 216-218). The engraved stamps are perforated gauge 14. The 35-lira stamp from the set is pictured nearby.

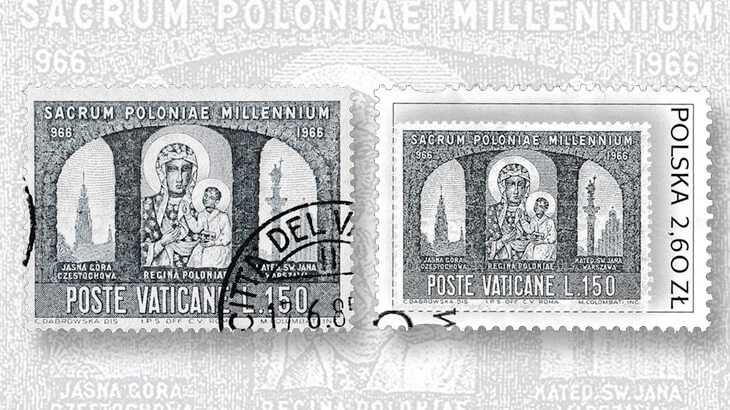

On May 3, 1966, Vatican City issued a set of six stamps (Scott 433-438) for the millennium of Polish Christianity.

The 150-lira stamp (Scott 437), shown at left in the third illustration, features the Black Madonna and the cloister and church of the Jasna Gora monastery. The engraved stamp is on paper watermarked with crossed keys and is perforated gauge 14 by gauge 13½.

This stamp was featured on a Polish stamp-on-stamp design issued Dec. 12, 2003, shown at right in the third picture. The Polish stamp was printed by lithography and is perforated gauge 11½ with horizontal syncopated perforations.

The stamps previously discussed show the icon without her crown (sheath). On June 18, 1992, Poland issued a 20,000z Black Madonna of Czestochowa souvenir sheet of one (Scott 3092), shown nearby, which depicts the icon wearing her crown.

The original crown was iron, but over the years it has been upgraded several times. The icon received additional canonical coronations from Pope Pius X on May 22, 1910, and from Pope John Paul II on Aug 26, 2005. Today the crown is of gold and silver and studded with jewels. When the crown is in place, only the faces and hands of Mary and Jesus in the icon are visible.

August 26 is the feast day of the icon. Although Jasna Gora is a Roman Catholic monastery, the Black Madonna has a strong following among Orthodox believers in both Ukraine and Belarus.

Jasna Gora is the most well-known and popular shrine in Poland, with a 140-mile pilgrimage held annually since 1711.

During World War II and the dark days of the long communist occupation after the war, many faithful Christians, including Karol Wojtyla, the future St. John Paul II, risked their lives and liberty to perform the pilgrimage clandestinely.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers