World Stamps

Canada’s Maple Leaf flag celebrates 50th anniversary

On Feb. 15 — 50 years to the day after it first ran up the flagpole on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada — the red Maple Leaf flag was honored by Canada Post with a new domestic-letter rate stamp, postal card and an innovative $5 Flag souvenir sheet.

Measuring 40 millimeters by 32mm, the booklet commemorative depicts the flag against a blue sky shaded with the number “50,” and “1965-2015” to hail its first half-century.

The letter “P” on a white maple-leaf background shows it is denominated for permanent use to prepay a basic first-class letter within Canada. The current rate is 85¢.

Printed by Lowe-Martin in five-color lithography, the 10-stamp self-adhesive booklets sell for $8.50, and are item 413974111.

A matching domestic-rate picture postal cards showing the flag against a blue sky is item 262428, selling at $2.50 each in the January-February 2015 issue of Canada Post’s Details magazine.

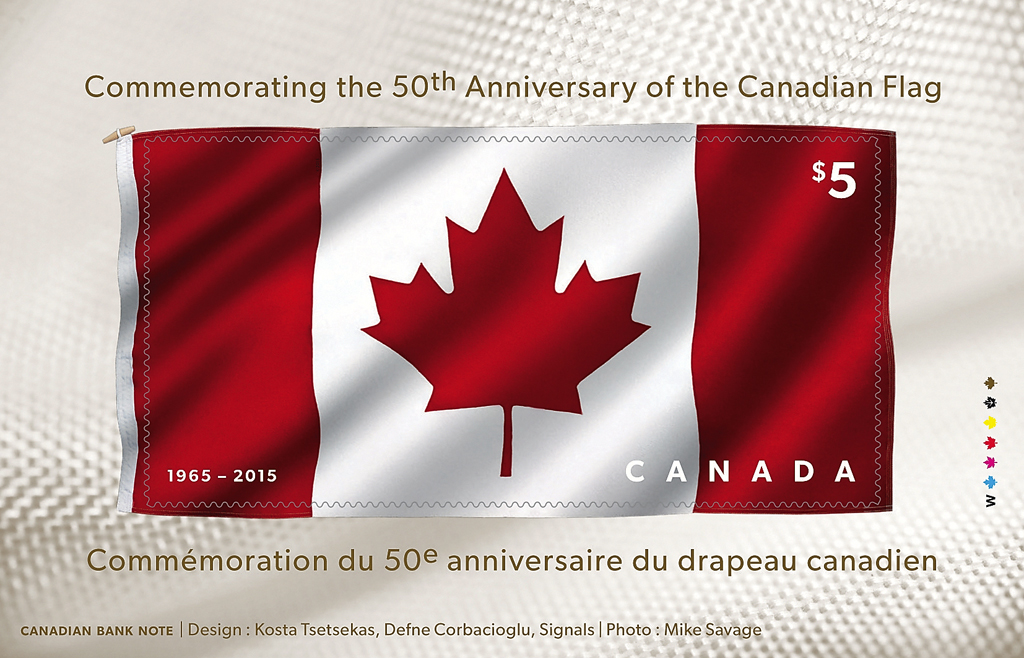

In a size that can’t be missed and a high denomination sure to provoke critics, the new $5 Flag souvenir sheet measures 140mm by 90mm, roughly 5½ by 3½ inches.

Canada Post is billing the souvenir sheet as “Canada Post’s first fabric stamp,” though that may draw controversy, too.

In a nation renowned for pulp and paper, the printing medium celebrating this quintessentially Canadian icon comes from a producer in central Wisconsin.

“Made by Wausau Coated Products,” as Details states, “the print stock consists of a specialized satin rayon fabric applied, using adhesives and silicones, to a paper backer similar to, but thicker than, that used with most postage pressure-sensitive stamps [sic].”

The souvenir sheet includes English and French inscriptions “Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Canadian Flag” above and below a 100mm by 50mm $5 Flag stamp inscribed “1965-2015.”

Printed by Canadian Bank Note Co., the souvenir sheet is Canada Post item 403974145.

Like the booklet stamp and picture postal card, it was designed by Kosta Tsetsekas and Defne Corbacioglu of Signals, a Vancouver-based design firm.

Details devotes a page to uncut press sheets of 20 souvenir sheets with what look like three all-fabric stamps printed vertically along the right margin of the horizontally formatted sheet.

Marketed in a “Limited edition ... Only 1,000 available,” the uncut sheets are “signed” by “Joan O’Malley, who sewed prototypes of the Canadian flag” in the 1960s.”

Canada Post also reports in Details that the numbered sheets include invisible security ink applied to “areas of the flag.” This ink glows in the dark under a UV lamp.

Listed as item 403974148, uncut press sheets are $115 each.

Canada Post products are available at online; by mail order from the National Philatelic Center, Canada Post Corp., 75 St. Ninian St., Antigonish, NS B2G 2R8, Canada; or by telephone from the United States and Canada at 800-565-4362, and from other countries at 902-863-6550.

Canada’s stamps and stamp products are also available from many new-issue stamp dealers, and from Canada Post’s agent in the United States: Interpost, Box 420, Hewlett, NY 11557.

Related posts:

- Rejected flag designs

- Canada Post announces 2015 stamp program; subjects include FIFA Women's World Cup

- New Canada stamp pays tribute to honorary Canadian citizen Mandela

How it came to be

As I’ve already mentioned, 50 years ago Canada got a new flag, along with a new 5¢ stamp to unveil it (Scott 439).

Although the flag caused heated debate, few today recall why it was so high on the to-do list of newly elected Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson in 1963.

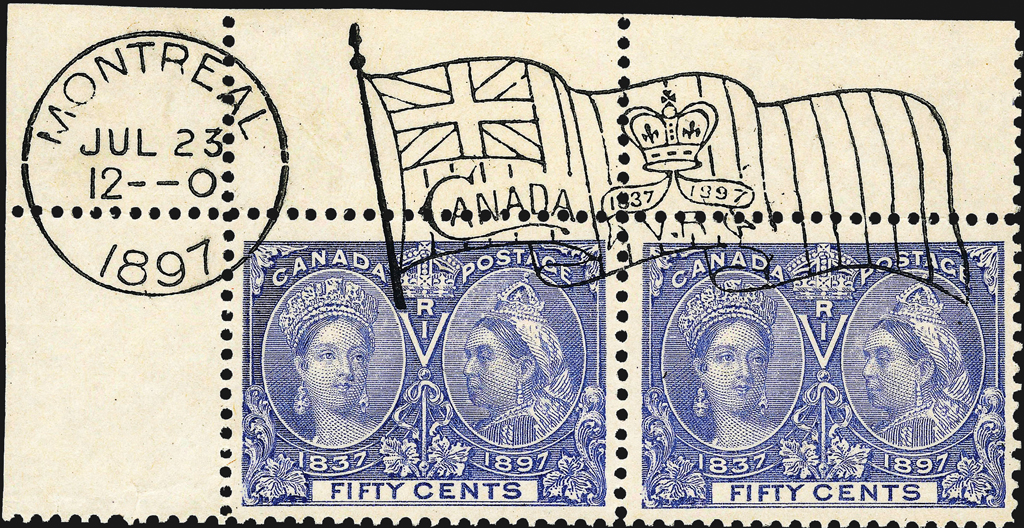

Canada already had a flag. In use since 1868, Great Britain’s Union Jack fills the top-left quarter of this red ensign, with a small coat of arms at right, symbolic of Canada’s British heritage and other founding nations.

The flag machine cancel on a pair of 50¢ stamps (Scott 60) shows a stylized version of the design, adapted for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897.

Carried proudly by Canadians from the Boer War to Korea, this banner became a problem during the Suez Crisis of 1956, after Egypt discarded the treaties that kept the canal open, nationalized it, and closed it to Israel.

The crisis arose when Great Britain, France and Israel intervened militarily to restore the status quo ante.

Pearson, then Canada’s secretary of state, wanted a multinational force under United Nations control to restore peace in the region, and proposed impartial Canadian troops to police the cease-fire.

Egypt objected, pointing to that red ensign: How could Egypt trust Canadian neutrality when Canadian troops marched under Great Britain’s Union Jack?

In the end, Canada sent peacekeepers under the United Nations, and the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize went to Pearson.

But he quietly resolved to make a new Canadian flag a priority when he gained power.

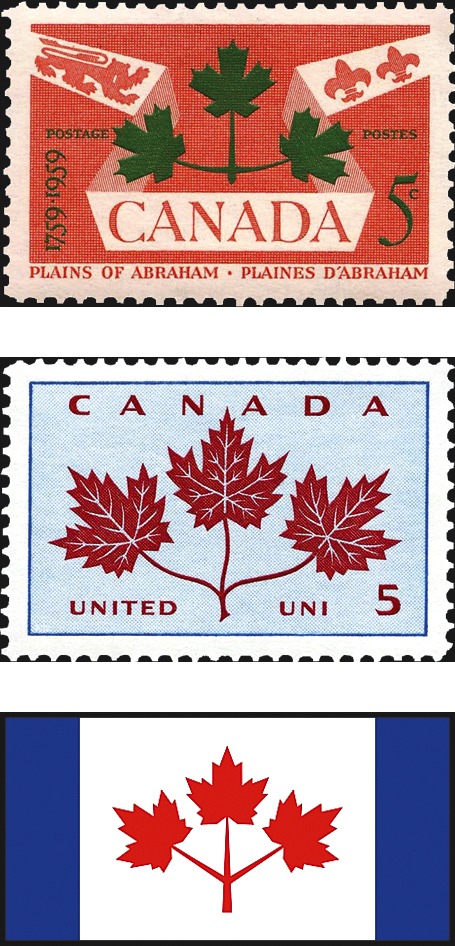

He had a design in mind, too: three red leaves (a nod to the old ensign) for the natives, English and French who created Canada, with blue bars at each end for the Atlantic and Pacific.

The design is shown nearby, beneath two similar Canadian stamps.

At left is a 5¢ stamp for the 1959 bicentennial of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (Scott 388), the decisive conflict by which Britain took control of Canada from the French. The stamp is an allegory of reconciliation: a British lion on the left, a French fleur-de-lis on the right, flanking a middle leaf for national unity.

At right is the 1964 5¢ Canada Unity stamp showing three red leaves on a pale blue background (Scott 417). Ostensibly the first stamp in a set of Canada’s provincial coats of arms, it’s hard not to see this now as a test balloon for what came to be scorned as “Pearson’s pennant” by its detractors.

To choose a flag, a nonpartisan committee looked at 3,541 designs sent in by the public. Maple leaves appeared on 2,136 of these.

In the end, at the last moment, the committee settled on the proposal of George Stanley, then teaching at Canada’s Royal Military College at Kingston, Ontario.

Stanley had a few simple and wise criteria for his design: It should not divide people, it should be distinctively recognizable, and simple enough that a schoolchild would be able to draw it. And so it came to be.

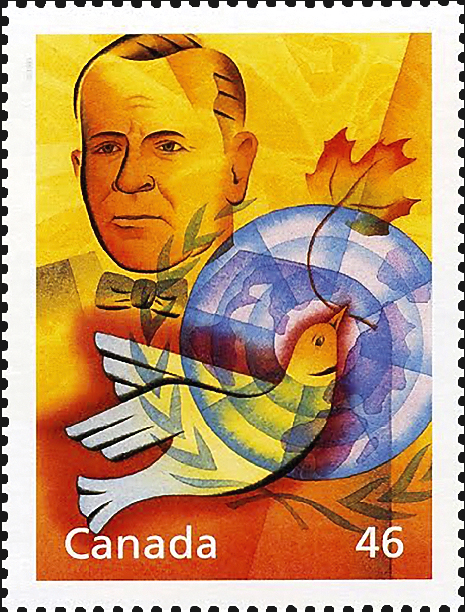

This tale explains the otherwise rather baffling design of one of the many 46¢ Millennium commemoratives Canada issued in 2000 (Scott 1825c). In the background is Pearson sporting his signature bow tie, while in the foreground a white dove is superimposed on a barely recognizable U.N. emblem in blue.

And now you know the story — and why, in its beak, this dove of peace holds not an olive branch, but a single, red maple leaf.

More from Linns.com:

35 rare 5c China Imperial Dragons found in attic in UK

Jenny Invert to be auctioned in Siegel sale of Curtis collection

Court rules USPS must pay 37¢ Korean War artist $540,000

Iwo Jima 1945, the photograph and the 3¢ green stamp

Stars and Stripes theme for new U.S. presorted standard coils

Keep up with all of Linns.com's news and insights by signing up for our free eNewsletters, liking us on Facebook, and following us on Twitter.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

Postal Updates

Oct 7, 2024, 5 PMUSPS plans to raise postal rates five times in next three years

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available