World Stamps

Cuba 1910 Patriots set marked return to home rule

By Kathleen Wunderly

As in so many parts of the world since the beginning of history, Cuba, the largest island in the Caribbean, has repeatedly been invaded, fought over, and occupied.

First came the Spanish, conquering the resident Amerindians in 1510. Over the next two centuries, visiting aggressors included the French, the Dutch, and the English, some repeatedly, but essentially Cuba was Spain’s colony since the first visit in the 16th century.

By the 1860s, the Cuban population was a complex mixture of white people, free people of color (mixed-race), black slaves and “imported” slaves that included Chinese. Growing hostility against Spanish rule led to the first war of Cuban independence, also known as the Ten Years’ War, 1868-78.

The uprising never really stopped, but the next major Cuban revolution is generally considered to have been from 1895-98, entangled with the Spanish-American War in 1898 (remember the Maine).

Connect with Linn's Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

The Treaty of Paris on Dec. 10, 1898, ended the Spanish-American War, and Spain relinquished sovereignty over Cuba, ceding power to the United States.

A U.S. provisional governor took control, and 1898 Cuba postage stamps surcharged in cents were used, until a pictorial set of Cuban subjects — palms, a cane field, and so on — was issued in 1899 (Scott 227-231).

A Cuban republic was briefly established during 1902-06, the 1898 issues were surcharged, and some denominations of the 1899 stamps were re-engraved and used until 1907.

A revolt against the president brought U.S. troops back, and a U.S. governor was in charge again as of October 1906.

Home rule returned to Cuba on Jan. 28, 1909, and a new set of portrait stamps was issued Feb. 1, 1910. Their designs closely resemble the single issue of 1907, Scott 238, which portrays Maj. Gen. Jose Antonio Maceo y Grajales, who was killed in the 1895-98 revolution and is considered by many historians to be the greatest Cuban war general.

The 1910 set includes eight regular stamps (Scott 239-246), a special delivery stamp (E4), and seven telegraph stamps.

All of the men depicted on the postage stamps were generals in the two wars of independence; the telegraph stamps include military men and politicians.

In their 1988 Handbook of Cuba, Part III, The Republic 1902-1961, William McP. Jones and R.J. Roy Jr., wrote that the stamp subjects were the idea of collectors, “initially proposed by the Sociedad Filatelica de Cuba in June of 1904, and a number of Cuban heroes were selected in 1909 to be honored on the projected ‘Patriots’ issue.”

Jones and Roy relate that a search ensued of archives and family albums to find photographs and portraits from which authentic images of the subjects could be made.

The bicolor stamps were engraved and recess printed in panes of 100 by American Bank Note Co. of New York.

Jones and Roy state that advance reports of the stamps said they would be printed on watermarked paper with an “R” interwoven with a “C,” but the additional cost of the special watermarked paper led the government to select instead white, wove, unwatermarked paper. The stamps are perforated gauge 12.

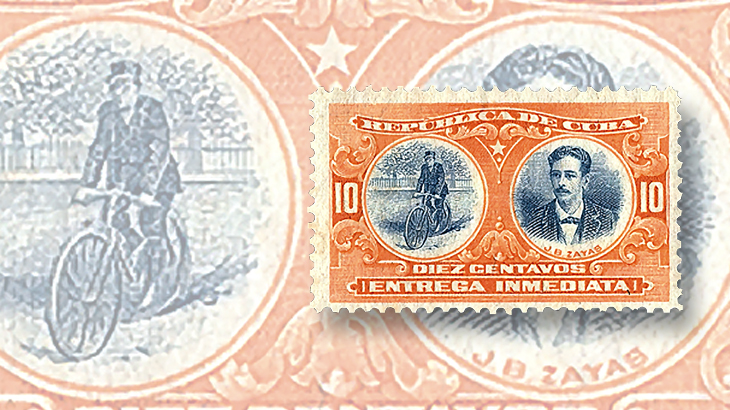

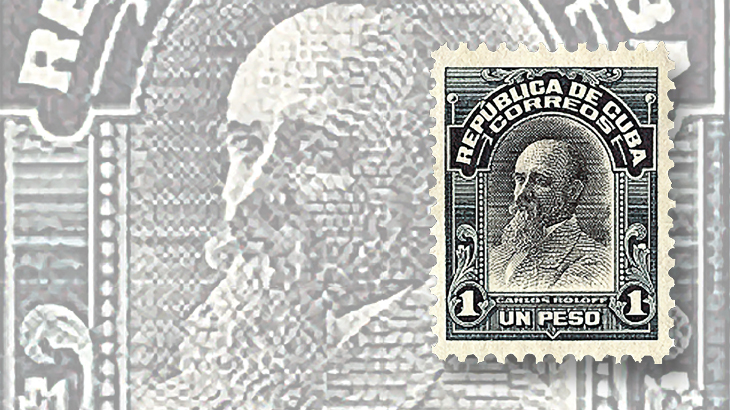

The designs, denominations and colors are as follows: Scott 239, 1 centavo green and violet Bartolome Maso y Marquez; 240, 2c carmine and green Maximo Gomez y Baez; 241, 3c violet and blue Julio Sanguily y Garritte; 242, 5c blue and green Ignacio Agramonte y Loynaz; 243, 8c olive and violet Calixto Garcia y Iniguez; 244, 10c brown and blue Jose Maria Rodriguez y Rodriguez; 245, 50c violet and black Jose Antonio Maceo Grajales; 246, 1 peso slate and black Carlos Roloff y Miaflosky; E4, 10c orange and blue with a messenger on a bicycle at left and Juan Bruno Zayas y Alfonso at right.

Inverted examples of the 1c, 2c and 10c regular issues and the 10c special delivery stamp were discovered soon after the stamps were released and reported to U.S. stamp publications. The discussions continued in the next few years.

Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News of July 1, 1911, quoted the Revista del Circulo Filatelico de Cuba of April 1911, which expressed having been “very much surprised” by the news of the inverts, because “the seriousness, respectability and honorableness of a firm as the American Bank Note Co.” made it difficult to believe in the alleged errors. However, after considering the evidence before their eyes, the publication was forced to accept the inverts’ reality, while still believing that “some very few examples were ‘placed’ in determined spots for motives of propaganda and popularity, the main bulk of the stamps [being] in the hands of persons well known to us, and that these people hardly need to make a business out of these stamps.”

The inverts surely had nothing to do with seriousness or honor and everything to do with the hazards inherent in two-color printing, in which each sheet of stamps must be placed on the printing press two separate times. The error-prone bicolor process resulted in U.S. stamp inverts in 1869, 1901 and, most famously, in 1918, with the 24¢ Inverted Jenny (Scott C3a).

The press run for the 1c Maso y Marquez stamp was four million examples, and Jones and Roy’s 1988 handbook tallied 1,100 inverts (Scott 239a) found. Of the eight million 2c Gomez y Baez stamps printed, only 200 errors (240a) were found.

The authors reported 100 inverts (Scott 244a) of the 10c Rodriguez y Rodriguez stamps (500,000 printed) and 200 inverts (E4a) of the 10c special delivery stamps (200,000 printed).

As valued by the 2016 Scott Classic Specialized Catalogue of Stamps and Covers 1840-1940, acquiring an unused set of the regular Patriots stamps plus the special delivery stamp would cost about $65; a used set would cost not much more than $10.

As expected, the inverts are another story: $260 for Scott 239a; $575 for 240a; $850 for 244a; and $1,250 for the scarce E4a.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers