World Stamps

Exploring creative philatelic entrepreneur Nicholas Frederick Seebeck

By Christer Brunstrom

There is more than one reason to look back at philatelic history from time to time.

It is interesting to spend a few moments reflecting on the attitude of the stamp collecting community to these tiny bits of paper and the ways they are marketed.

A philatelic friend recently suggested a most interesting topic. He had always been fascinated by a man named Seebeck who was deeply involved in the printing and marketing of stamps more than a century ago.

Seebeck’s name still pops up at regular intervals, and especially so in the Central American sections of our stamp catalogs.

Now, who was Nicholas Frederick Seebeck?

He was born in Germany in 1857, and in common with many of his compatriots, he and his family moved to the United States in search of a better future.

Nicholas Frederick was 9 when the family settled in New York City. Quite early on, he got involved in the printing business. He also began dealing in postage stamps for collectors.

In 1876, he compiled and published a stamp catalog with the rather lengthy title Descriptive Price Catalogue of All Known Postage Stamps of the United States and Foreign Countries. During the following years, there were several new printings of the catalog.

In 1879, he was the go-between for the printing of the stamps of the Dominican Republic. He also secured a stamp printing contract with the Colombian state of Bolivar.

Seebeck then had the smart idea of dating the Bolivar stamps with the year of validity. Thus there was a need to release a new set each year. The Bolivar stamps were printed by the Manhattan Bank Note Co. in New York. Seebeck’s association with Bolivar lasted until 1886.

In 1884, he sold his printing business for $10,000. He used the money to buy a large part of the Hamilton Bank Note Engraving and Printing Co. in New York.

The following year, he sold his part for $28,500. Seebeck certainly seems to have been a shrewd businessman. He also was given a leading position in the company.

The Hamilton Bank Note Co. did not really specialize in postage stamps; rather, the firm printed tickets for railways and toll bridges in the State of New York.

Brother-in-law Ernest Schernikow was an important person in Seebeck’s future career. He was consul in New York for both El Salvador and Honduras.

When Seebeck went on a trip to Central America in 1889, he brought along a letter of introduction from Schernikow. Thanks to this letter, he was able to meet with several government officials and introduce his plans to them.

His idea was to offer a win-win plan for the postal departments of a number of Latin American countries. Seebeck would provide postage stamps and postal stationery on a yearly basis, free of charge.

At the end of the year, the administrations would return the remainders to Seebeck, who then intended to sell them to worldwide stamp collectors.

Many of the countries that Seebeck visited had very weak economies. His plan thus seemed more than advantageous to local officials, and he was able to sign contracts with Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala (only revenue stamps) and Nicaragua.

Let’s now take a closer look at the main features of the Nicaraguan contract, which was signed in Managua on May 4, 1889.

Seebeck undertook to deliver two million postage stamps and as many as 225,000 postal stationery items for a period of one or two years, at no cost to Nicaragua.

The stamp designs would be changed each year or every second year. All denominations in a set would have the same design, but the stamps would be printed in different colors. After a year or two, the stamps would be invalidated.

The government of Nicaragua undertook to deliver all stocks of the country’s stamps issued before 1889 and to return all remainders of future issues to Seebeck. The government authorized Seebeck to sell these stamps to collectors.

The contract also included a paragraph giving Seebeck permission to reprint stamps if need be. Nicaragua had no right to sell its stamps at a price that was lower than 90 percent of face value. The contract was to be valid for 10 years.

The arrangement started within a few months. In 1890, the first issue printed by the Hamilton Bank Note Co. went on sale in Nicaragua. It is a nice design featuring a steam locomotive and a telegraph key. The set comprises 10 denominations ranging from 1 centavo to 5 pesos.

The postage rates in 1890s Nicaragua were very low, and thus there was a very limited need for the larger denominations.

After the 1890 set, there was a new set each year. Some had very interesting designs. In 1892, the stamps of course celebrated Christopher Columbus and his discovery of America. The stamps for 1896 and 1897 feature a map of Nicaragua.

All these stamps still have low catalog values today. In many cases, it is extremely difficult to distinguish between the originals and the reprints — Seebeck was very quick to take advantage of that particular clause in the contract.

Genuinely canceled stamps during the period of issue are generally scarce, but many issues also exist canceled-to-order in large quantities.

Some of the original stamps from the latter years of the contract period are scarce today, while the reprints can be obtained for pennies. Commercial covers franked with original Seebeck stamps and bearing contemporaneous postmarks are very rare.

It seems the various contracts were not identical. Seebeck produced issues for El Salvador with common designs on all stamps, and also multiple-design issues. In 1893, there were three high denominations devoted to Columbus. A 10-peso stamp depicting Columbus leaving the Spanish port of Palos on his epic journey to America is pictured here. Some experts believe that this issue was never put into use.

In 1896, there was a magnificent set of 12 stamps that all had different designs. This particular issue is suitable for specialization because it exists on paper with and without watermark, and perforated and imperforate. The reprints are on a thicker paper.

Both El Salvador and Nicaragua completed their contracts with Seebeck. Honduras somehow managed to end the arrangement in 1893.

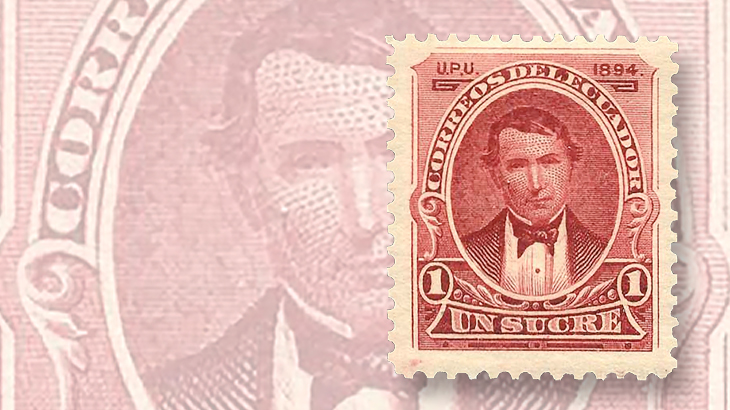

Ecuador terminated its contract with Seebeck in 1896. Ecuador’s 1894 and 1895 stamps depict President Vincente Rocafuerte.

In 1884, Seebeck sold his stamp-dealing business. The buyer was Gustav B. Calman, who also was of German origin.

Swedish philatelic writer Olle Cronsjo discussed the Seebeck issues in one of his books. According to Cronsjo, it was Calman who was the driving force behind the scheme and Seebeck only served as a front.

Today we don’t really know the exact relationship between these two men, but it was Calman who distributed the stamps to the trade.

The Latin American governments soon realized that the Seebeck contracts were far from advantageous. They appear to have completely lost control of their own stamp issues.

Stamp collectors also reacted strongly when they found out how it all worked. Around 1892-93, Seebeck produced numerous stamps marking the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America. The choice of subject was obviously a good one, but collectors objected to the many unnecessary stamps with hefty denominations.

Seebeck’s stamp issues ruined the philatelic reputation of a handful of Latin American nations. In fact, I very much doubt that the reputation has been recovered despite the fact that more than a century has passed since Seebeck inundated the philatelic marketplace with large quantities of inexpensive stamps.

Interestingly enough, Seebeck passed away in 1899, the same year the contracts with El Salvador and Nicaragua expired. Calman continued to order new printings of the stamps even after the scheme had ended.

In retrospect, Seebeck’s activities in the late 1800s were rather limited, and many of his stamps had interesting designs and were of high artistic and technical quality.

Collecting Seebeck issues is quite a popular activity today. Most of the issues are still very affordable, and there are numerous varieties that can be added, making it an inexpensive and fun sideline collection.

However, to keep it inexpensive, you will have to stay away from postal history items, because they are very scarce and seldom available.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers