World Stamps

International airmail covers recall the ‘Day of Infamy’

By Ken Lawrence

After Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared Dec. 7, 1941, to be “a day which will live in infamy.” (In the rest of this article all dates are 1941 unless a different year is indicated.)

For airmail and postal history hobbyists, Pearl Harbor Day has become a benchmark date. In the marketplace, it can cause prices of some covers to soar, but a successful search for mail in transit to and from foreign countries on that fateful day adds more than mere monetary consideration to a connoisseur’s collection.

Dec. 6 and 7 Flight of Anzac Clipper

What a difference a few hours can make!

Two covers franked with metered postage were mailed from a New York bank on Dec. 2 addressed to a bank in Tehran, Iran. Both were intended to be transported to San Francisco on a domestic flight, by Foreign Air Mail route No. 14 (FAM 14) from San Francisco to Singapore, onward from Singapore to Basra, Iraq, on a British Overseas Airways Corp. (BOAC) connecting flight, and from Basra to Tehran by a regional carrier. One cover caught the FAM 14 flight; the other missed it.

The first cover reached California in time to be sent onward aboard the Pan American Airways FAM 14 Anzac Clipper — a Boeing B-314A flying boat, registration No. NC 18611 — which departed San Francisco on the afternoon of Dec. 6. The plane actually had taken off late on the afternoon of Dec. 5, but experienced mechanical trouble 400 miles out and had to return to San Francisco. After being repaired, she had been rescheduled to leave at 2 p.m. California time on Dec. 6, but the veteran pilot, Capt. H. Lanier Turner, had been granted a brief postponement of the departure time, about half an hour, so he could attend his daughter’s first piano recital at Oakland.

At 8 a.m. the next morning, Anzac Clipper was less than an hour away from Honolulu when its radio officer received a coded flash warning that Pearl Harbor was under Japanese air attack. Turner’s providentially late departure from San Francisco had delayed his approach just long enough to have kept his vulnerable aircraft out of harm’s way.

Turner’s “Plan A” secret instructions in the event of war rerouted Anzac Clipper to Hilo, 220 miles southwest of the combat zone. Gen. Walter C. Short, the military governor of Hawaii, had immediately declared martial law in the islands and had ordered the newly created Information Control Board, headquartered beside the Honolulu post office, to open and examine all transit and outbound civil mail. Anzac Clipper’s mail was forwarded to Honolulu for censorship, denoted by the handstamped RELEASED BY I.C.B. 240 marking in black ink over the cellophane tape seal on my cover.

According to an article by George Hester and Jonathan L. Johnson Jr. in the April-June 1991 Bulletin of the Metropolitan Air Post Society, “The Anzac Clipper left Hilo for Treasure Island [San Francisco] on the same day. No known commercial mail was carried on the return flight.” The authoritative 1997 book Last of the Flying Clippers by M.D. Klaas states, “On the night of December 8th … the blackened Anzac Clipper, her cargo consisting only of mail accepted by the Hilo postmaster, departed for San Francisco without passengers.”

Considering the time required to apply camouflage paint to the huge aircraft, the night of Dec. 8 seems more probable to me than Dec. 7 as the departure date, but I’m skeptical that the return flight would have been allowed to carry commercial mail, and I have never seen a cover that could plausibly have been carried back to the U.S. mainland so soon after the Pearl Harbor attack. Perhaps Anzac Clipper carried back a load of official government and urgent military mail. Commercial airmail service to and from the mainland was restored with China Clipper’s Dec. 18 flight from San Francisco and its Dec. 19 return from Honolulu.

My cover probably went back on a later flight. Some letters transported to Hawaii on Anzac Clipper’s Dec. 6-7 outbound flight were not returned to the mainland until late February 1942. All covers mailed from the mainland to Hawaii before Pearl Harbor that received I.C.B. censorship markings — evidence of having been flown on the flight that was diverted to Hilo — are scarce, and are prized by specialists. A 1992 census by Johnson and Roland Rustad recorded 10; two decades later, the number I have seen or read about has not quite doubled their total. One example was pictured in the July-August 2015 Collectors Club Philatelist with an incorrect analysis of its subsequent trans-Atlantic route.

(For a measure of the survival and relative scarcity of important World War II covers, consider another census for comparison: In his 2006 book Passed by Army Censor, the late Richard W. Helbock, assisted by the late Robert D. Rawlins, recorded 52 covers from U.S. forces on the Bataan peninsula and Corregidor Island in the Philippines after Japanese invaders had blocked all escape routes. Letters that successfully ran the blockade by submarine, light aircraft, merchant vessel and PT-boat before the surrender on May 6, 1942, are treasured by specialists.)

On Dec. 18, the postmaster general had ordered all mail to countries in Asia and the Pacific previously served by FAM 14 to be rerouted via Miami for transport via the newly inaugurated FAM 22 route across Africa. Pan Am’s trans-Africa flights in the early months of 1942 were overloaded with urgently needed military shipments, so a lot of that mail got set aside until the backlog cleared. My cover finally arrived at Tehran on April 22, 1942, where it was examined by Anglo-Soviet-Persian censorship.

My second metered cover was posted at New York on the same day as the first, probably later that day, but missed Anzac Clipper’s departure from San Francisco. It must have been in the mail awaiting a westbound trans-Pacific flight when the postmaster general’s order redirected it to Miami for a trans-Atlantic flight instead. This letter was censored first by British Imperial Censorship at Trinidad; next at Cairo where it was backstamped March 11, 1942; next at Baghdad, passed by the Iraq censor without being opened March 16; and finally was examined by Anglo-Soviet-Persian censorship upon arrival at Tehran, more than a month before the first cover got there.

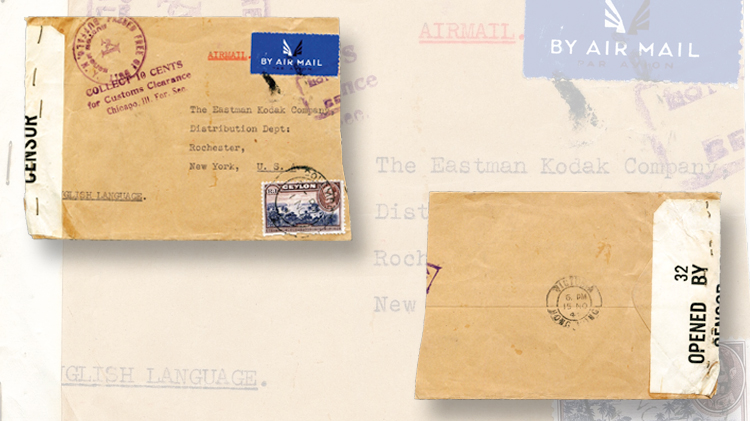

A third interesting cover from my collection probably arrived at San Francisco on Anzac Clipper’s last inbound flight before the United States went to war. It was posted Nov. 1 at Ceylon and censored before departure. A British flight carried it to Hong Kong Nov. 15. From there, a Hong Kong Clipper II shuttle flight took it to Manila for the Nov. 22 Anzac Clipper flight to San Francisco. After arrival Dec. 1, its domestic journey took it to Chicago, where a postal clerk directed it to the Buffalo, N.Y., customs office, nearest to its Rochester, N.Y., destination. Even though it was cleared duty-free, a mandatory 10¢ clearance fee was collected from the recipient on delivery.

‘The Last Flight Out’

A special report by the American Air Mail Society (AAMS) prepared for the Pacific 97 international stamp exhibition almost two decades ago stimulated my interest in these fascinating covers.

The 1997 edition of The Congress Book, an annual clothbound publication of the American Philatelic Congress, performed double duty as Pacific 97 Handbook, the show catalog, an excellent format for a scholarly reference book. Among the contributions was “The Last Flight Out: Seven Pan American Clippers on the Eve of Pearl Harbor” by AAMS.

“On December 7, 1941,” wrote the collectively anonymous authors, “seven Pan American clippers were operating in the Pacific, three of which were in the air at the moment Pearl Harbor was attacked.” Following brief profiles of each of the seven flying boats, their stories were illustrated by 15 covers that had been aboard those flights. (An eighth, the Boeing B-314 Honolulu Clipper [NC 18601] was out of service from October 1941 until January 1942.)

Partly as a consequence of that challenging article and a special exhibit titled “Pan Am’s Pacific Pathfinders” by Florida writer and collector Jon E. Krupnick, collecting airmail covers carried on the last Pan American Airways trans-Pacific flights before or during the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, Hong Kong, Guam, Malaya and Wake Island, and other letters mailed in time for those flights but that missed their connections, has evolved into a specialty of its own.

A lot has been learned since 1997 that was unknown to those authors, as previously closed and classified archived documents have been opened to scholars and as new histories have been published. This Linn’s Spotlight report, though inspired by the Pacific 97 compilation, relies on my personal research. In many instances my findings supplement and correct statements in that article (and a similar but shorter one titled “Final Crossing” by Robert E. Mattingly in the March 2013 Airpost Journal), but the Congress Book/Pacific 97 Handbook report remains the best introduction to this area of interest.

China Clipper’s Last Flight before War Engulfed the Pacific

China Clipper (NC 14716), the Martin M-130 flying boat that had inaugurated trans-Pacific airmail service in November 1935, had departed San Francisco on Nov. 19 for a routine FAM 14 flight across the Pacific to Singapore, Malaya, about 8,500 miles away, with stops en route at Honolulu, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam and Manila. My Nov. 18 cover from New York City to Manila, Philippine Islands, has a Nov. 28 Manila backstamp, which confirms that it was transported on that flight.

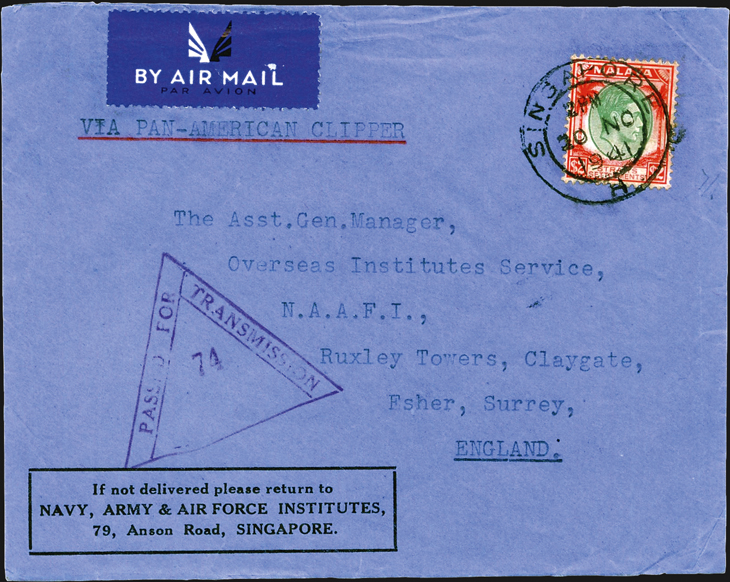

China Clipper went on to Singapore that same day, and began her eastbound return flight over the same trans-Pacific route on Nov. 29. A Nov. 20 airmail cover from Singapore to Great Britain flew to San Francisco on that flight after being examined and released by a British censor at Singapore. After arriving at San Francisco from the Far East on the morning of Dec. 6, several hours before the Anzac Clipper departed in the opposite direction, a domestic carrier took this letter across the North American continent to New York.

A trans-Atlantic Clipper carried it to Lisbon, and a BOAC/KLM flight carried it from Portugal to Great Britain. As a so-called two-ocean airmail cover, this would delight most airmail specialists regardless of the postmark date, but as a memento of China Clipper’s final prewar inbound flight, it is scarce and doubly special. Among the passengers on that trip was Maxim Litvinoff, the Soviet Union’s new ambassador to the United States, along with his wife and secretary.

After Pearl Harbor, China Clipper remained in Pacific service until 1944, when she was transferred to Atlantic service, initially serving the route between the United States and the Panama Canal Zone. In September 1944 she reopened Pan Am’s flying boat service from Miami to the Belgian Congo, and was flying that route when she crashed at Trinidad on Jan. 8, 1945, and was destroyed.

Philippine Clipper’s Harrowing Ordeal

China Clipper’s twin Martin M-130 flying boat, Philippine Clipper (NC 14715), also had begun flying the trans-Pacific route in 1935. Philippine Clipper’s last complete FAM 14 round trip before Pearl Harbor departed from San Francisco on Nov. 4, arrived at Singapore on Nov. 14, and returned to San Francisco on Nov. 27. A cover that probably was transported on the outbound flight is illustrated in the boxed sidebar.

On Dec. 3, Philippine Clipper took off again from San Francisco. She flew on from Honolulu the next day, and from Midway Island the next, arriving at Wake Island on Dec. 7, which was still Dec. 6 east of the International Date Line at Midway Island and Hawaii. After an overnight rest and refueling stop at Wake, she took off the next morning, on a westward course toward Guam.

Philippine Clipper had been airborne for about 20 minutes when she was called back to Wake Island on news that Pearl Harbor was under attack. After dumping 3,000 pounds of fuel for safety’s sake, the Pan Am pilot, Capt. John H. Hamilton, brought her back to the lagoon at Wake. Passengers, cargo and mail were unloaded, and she was refueled for the flight back to Midway.

A few hours later, Japanese aircraft attacked Wake Island and strafed the flying boat docked below. Robert J. Cressman wrote in his book “A Magnificent Fight” — The Battle for Wake Island:

Almost miraculously, the twenty-six-ton Philippine Clipper, empty of both passengers and cargo but fully refueled, rode easily at her moorings. A bomb had splashed one hundred feet ahead of her, and bullets had holed her in twenty-three places, but none had hit her large fuel tanks. …

Willing hands had stripped the Martin 130 of all superfluous equipment (and ejected two Guamians who attempted to stow away in the tail of the plane) and, soon thereafter, the five passengers (Herman Hevenor of the Bureau of the budget for some reason not among them) and the twenty-six Caucasian PanAir employees joined the eight-man crew on board the Philippine Clipper. After two anxious tries, Hamilton finally coaxed the fully loaded ship off the turquoise waters of the lagoon at 1330 and flew toward Midway.

Nine or ten of Pan Am’s Chamorro employees (American Pacific Islanders, usually residents of Guam) had been killed by Japanese bombs in the first bombing raid; the rest became internees or prisoners of war, exploited as slave laborers by their Japanese captors along with the island’s military defenders, civilian contractors, and Hevenor, the no-show passenger.

According to the Congress Book account, “After the Japanese occupation, the mail left on the dock was ransacked by soldiers, and then relegated to waste paper on an occupied island in a war zone. The possibility exists of mail carried on this plane, dispatched from the mainland to Honolulu, and received there on December 4.” One would probably need to find a registered cover with a Dec. 4 Honolulu backstamp as confirmation, which I have not found.

A later flight brought mail back from Wake Island. On Dec. 20, a Navy PBY-5 Catalina piloted by Ens. James J. Murphy arrived from Midway, the first friendly aircraft from the outside since the war began, with secret orders for the Navy and Marine defenders and a plan to evacuate civilians. Several of the men stranded on Wake, including Hevenor and Navy Cmdr. Winfield S. Cunningham, wrote letters that Murphy carried out on his return flight. Some are in archives and others are quoted in memoirs; I’m not aware of any in private collections, but one or more might be.

Murphy’s Dec. 21 departure was the last American flight out of Midway. The opportunity to evacuate civilians from Wake had passed. Outnumbered and outgunned U.S. Army, Navy, Marine and civilian defenders put up a valiant fight, sank two enemy destroyers, and shot down an estimated 21 warplanes. Reinforcements never arrived. Overwhelmed by superior force, the American survivors on Wake Island surrendered on Dec. 23.

Renaming Boeing Clippers in 1941: A Summary

Earlier in 1941, Pan Am had renamed several of the Boeing B-314 and B-314A flying boats without notifying the public, some of them more than once. (B-314A was Pan Am’s designation for the revised design of the aircraft, called A314 by Boeing, which had increased fuel capacity and promised improved engine performance.) To keep score of the name changes, it’s best to include each plane’s permanent registration number for the sake of reliable identification. Even then, this sequence is complicated, and has frustrated generations of airmail specialists.

Name changes began in May, initially as a ruse to deceive and mislead foreign spies, shortly after the FAM 14 route was extended to Singapore. The aircraft that flew the inaugural flight from San Francisco on May 2 was the California Clipper (NC 16802), completing its round trip back to California on May 20. That flight carried only mail. One day later, the first passenger flight took off for Singapore with the name “California Clipper” painted on her bow, but was actually the first of Pan Am’s B-314A model seaplanes to be put into service, NC 16809.

The original California Clipper (NC 16802) had been taken out of service for a major overhaul and upgrade to B-314A status. With those enhancements, and with the name removed from her bow, she was transferred to Miami and assigned to fly secret special missions across the South Atlantic for the military. Meanwhile, after returning from Singapore to San Francisco, the California Clipper alias was removed from NC 16809. She was christened Pacific Clipper and repainted with that name.

Pan Am had planned a maiden flight in June over the FAM 19 South Pacific route from San Francisco to New Zealand for its new Boeing B-314A eponymously christened Anzac Clipper (NC 16811). Boeing failed to deliver the real Anzac Clipper on schedule, so NC 18609 was disguised as Anzac Clipper for that occasion, but then the Anzac’s pretend maiden flight, faked by the temporarily renamed Pacific Clipper (NC 16809) in new disguise, was switched at the last minute to the FAM 14 route to Singapore, which departed San Francisco July 15, welcomed on arrival by six Australian and New Zealand officers stationed at Malaya.

After that, the real Anzac Clipper (NC 16811) remained on the FAM 14 route to Singapore despite its mismatched name, while Pacific Clipper (NC 16809) served the FAM 19 route to Auckland. She had been scheduled to make the inaugural flight in November when Fiji became an added call between Canton Island and New Caledonia, but Pan Am had ferried NC 16809 to New York in September, swapping her for the older American Clipper (NC 16806). At New York, Pacific Clipper (NC 16809) was renamed South Atlantic Clipper, but she was briefly returned to the Pacific after Pearl Harbor for emergency flights to and from Hawaii.

California Clipper, alias Pacific Clipper

After NC 16802, previously named California Clipper, had completed her secret special-mission military flights out of Miami, she returned to San Francisco, serving both the FAM 14 route between San Francisco to Singapore and the South Pacific route between California and New Zealand. In November, Fiji was added as a FAM 19 call between Canton Island and New Caledonia.

According to Last of the Flying Clippers, “With the removal of the Pacific Clipper [NC 16809] from the Pacific Division, [another] 314 name change occurred. Clippers flying south to Auckland, regardless of given names, were advertised and posted under the Pacific Clipper appellation. … The 314 assigned to make the Fiji trip was NC-02 which had been returned to Treasure Island in A314 status. For the flight she was press-posted as being the Pacific Clipper.”

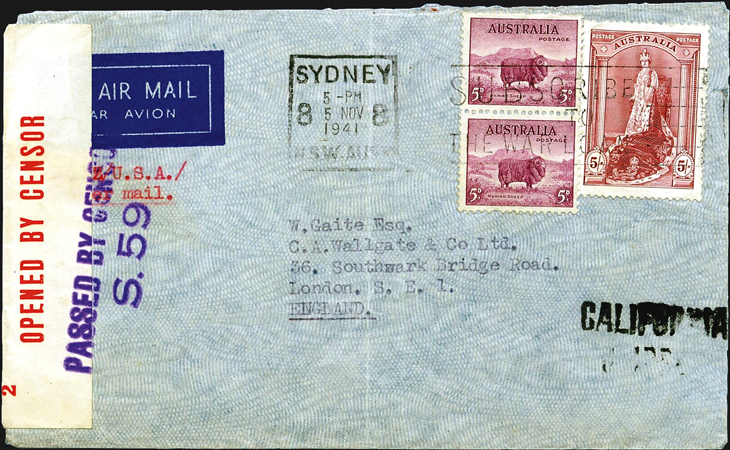

Despite that change, NC 16802 had still been designated California Clipper for her final prewar inbound flight, which departed New Zealand on Nov. 25 and arrived at San Francisco on Nov. 30. A Nov. 5 two-ocean airmail cover from Sydney, Australia, to London, England, illustrated here, probably was transported to America on that flight. The handstamped CALIFORNIA CLIPPER endorsement in black ink, struck at Sydney, did not refer specifically to the flying boat of that name. Its purpose was to direct the letter by the eastbound routes across two oceans instead of by the less expensive, longer, slower westbound BOAC Horseshoe Route via Asia and Africa.

Adding a final note of confusion to the flurry of name changes, when American Clipper (NC 16806) departed San Francisco on her Dec. 1 shuttle flight to Honolulu, some newspapers reported that flying boat as Pacific Clipper. The truth was more complicated. Pacific Clipper (NC 16802) actually did not leave San Francisco until Dec. 4, but Capt. Robert Ford and his crew, who were assigned to fly her to New Zealand, had flown American Clipper to Honolulu and were waiting there to take over the controls of Pacific Clipper (NC 16802) for the rest of the run to Auckland.

The stage was now set for one of the greatest feats in aviation history.

Pacific Clipper Circles the Globe

Ford and his crew transferred to Pacific Clipper (NC 16802), formerly named California Clipper, and departed Honolulu for the South Pacific on Dec. 4, leaving American Clipper to make her final shuttle flight back to California. They arrived at Canton Island that evening, and departed for Fiji the next morning, with a rest and refueling stop that night. On Dec. 6, they flew from Fiji to New Caledonia, the next refueling stop.

On the morning of Dec. 7, en route from New Caledonia to New Zealand, Pacific Clipper received the news flash that Pearl Harbor was under attack. Upon landing at Auckland, Ford went straight to the U.S. consulate to get his orders while passengers, cargo and mail were being unloaded. Considering the heroism of her trip home, letters carried on this flight are linked to a legend for the ages, worthy of Hollywood treatment.

Despite their obvious historical interest and aerophilatelic importance, I have recorded only four covers flown on Pacific Clipper’s storied flight. The one in my collection is shown here, posted Nov. 30 at New York City, addressed to a British military man in Sydney, Australia.

From New Zealand, a Dec. 9 or 10 TEAL flight carried it to Sydney, but by the time it arrived there on Dec. 12, the addressee had been transferred to Jerusalem, Palestine. After examination by an Australian censor, it was forwarded by BOAC’s Horseshoe Route, departing Sydney Dec. 18 and arriving at Tiberias, Palestine, on Dec. 29. Markings struck at Jerusalem on Dec. 31 and Jan. 2, 1942, document the end of its journey.

That was quite a trip for one cover, but no match for Pacific Clipper’s subsequent adventure. After receiving his orders to proceed to the United States by flying westward, Ford took her back to Noumea, New Caledonia, to evacuate 23 Pan Am employees to Gladstone, Australia. After Gladstone she flew to Darwin, and from there to Surabaya, Java, in the Dutch East Indies.

Only automobile gasoline was available at Surabaya, so Pacific Clipper’s engines, coughing and backfiring in protest, had to run on nonstandard low-octane fuel over the long hop to Trincomalee, Ceylon. Departing Ceylon on Christmas Eve, one of her engines leaked oil, which required a return to Trincomalee. After repair of a cylinder that had broken loose, she departed for Karachi, India, the day after Christmas, and from Karachi to Bahrain on Dec. 28.

Once again only automobile gasoline was available for the flight from Bahrain. Although Saudi Arabia had refused permission for Pacific Clipper to fly over its territory, Ford flouted that order and took the shortest route to Khartoum, Sudan, on Dec. 29. The crew spent two days there restocking provisions.

Lifting off the Nile River at Khartoum on New Year’s Day, a section of exhaust pipe broke off one engine, one more mishap on the long flight home. Her next stop was the Belgian Congo. From Leopoldville on Jan. 2, 1942, she flew nonstop to Natal, Brazil. After that she followed the normal South Atlantic route to Trinidad and New York, concluding her epic voyage at La Guardia’s Marine Air Terminal on Jan. 6.

Pacific Clipper had completed the first round-the-world flight by a commercial airliner — an air route of 31,500 miles from San Francisco to New York that touched five continents in a total of 209½ hours of flying time. The New York World Telegram called it “the greatest achievement in aviation since the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk.”

American Clipper, the last San Francisco-Los Angeles-Honolulu shuttle

As noted above, Ford had flown from California to Hawaii as pilot of American Clipper (NC 16806) and at Honolulu he had switched to Pacific Clipper (NC 16802), the flying boat that he flew onward to New Zealand and then westward around the world to New York. The former trip was American Clipper’s last outbound prewar flight.

Plans to shift a Boeing flying boat from California back to Miami had been percolating since November. The most expendable trans-Pacific airmail and passenger service consisted of thrice-weekly Pan Am shuttle flights between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Honolulu, which had begun in August.

The Nov. 17 Postal Bulletin and the November monthly supplement to the Official Postal Guide had announced that those shuttle flights would cease effective Nov. 22, but the Nov. 25 Bulletin and the December supplement to the Guide extended the deadline: “Service on the shuttle flights will be provided to December 3, instead of November 22.”

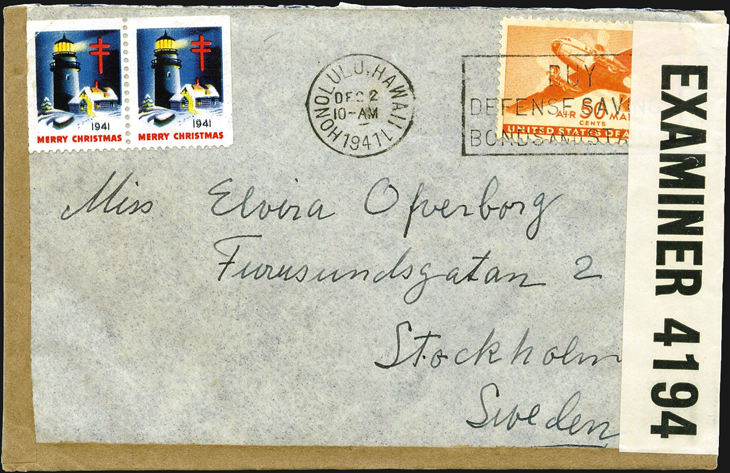

A Dec. 2 two-ocean airmail cover from Honolulu to Stockholm, Sweden, is a relic of the final inbound shuttle flight, which departed Honolulu Dec. 4 and returned to Los Angeles and San Francisco Dec. 5, bringing to California the last mail that had been posted at Hawaii before the service ended.

The Dec. 5 San Diego Union reported, “[Pan Am’s] shuttle service between California and Hawaii was discontinued yesterday when the huge passenger plane employed in this service was taken over by the government. It is reported the clipper will be used in the new service between Miami and Africa.”

The first recorded flight of American Clipper (NC 18606) from Miami was a Dec. 26 special mission to Leopoldville, Belgian Congo, and Calcutta, India, which returned to Miami on Jan. 12, 1942.

Hong Kong Clipper II, the Manila-Macao-Hong Kong shuttle

A Sikorsky S-42B flying boat, Hong Kong Clipper II (NC 16735) was the shuttle aircraft that carried passengers and airmail twice weekly between Hong Kong, Macao, and the Philippines, connecting at Manila to the trans-Pacific route between Singapore and San Francisco. In the opposite direction, CNAC connected Pan Am flights with principal cities in China, and to Burma, where CNAC transferred passengers and mail to and from BOAC Horseshoe Route service between Australia and South Africa.

On Dec. 8, Hong Kong Clipper II was fueled and ready for her scheduled departure to Manila. Six hours after the Pearl Harbor attack started, about 35 Japanese dive bombers strafed and bombed targets at Hong Kong; among the casualties was Pan Am’s flying boat, burned to the waterline. Fortunately the airline’s employees escaped on CNAC aircraft that departed to the interior of China after midnight under cover of darkness.

Before Pearl Harbor, mail from unoccupied China had a westbound route to the United States by BOAC’s Horseshoe Route and an eastbound route by Pan Am’s FAM 14. The BOAC service is illustrated by a Nov. 16 registered airmail cover in my collection from Sanhop, China, to Cambridge, Mass. A Nov. 27 registered airmail cover from Shanghai to Canon City, Colo., endorsed for the eastbound route wasn’t so lucky.

Destruction of Hong Kong Clipper II stranded the Shanghai letter at Hong Kong. More than a year later it returned to Shanghai, and from there it eventually made its way to America, was censored at New York on March 15, 1943, and was delivered at Canon City on March 22. It might have left China in a neutral country’s vessel or diplomatic pouch.

No heroic escape route could save Hong Kong Clipper II. Surviving covers that had been trapped at Hong Kong awaiting departure are scarce. Today they remind us of that flying boat’s tragic demise.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers