World Stamps

New British stamps celebrate industrial, electrical revolutions

By Charles Snee

A set of 10 new stamps from Great Britain’s Royal Mail pays tribute to important developments and advancements of the industrial and electrical revolutions.

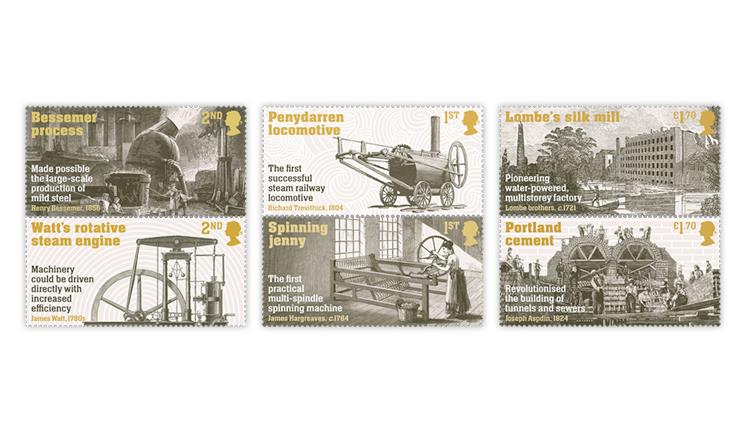

Royal Mail is issuing its Industrial Revolutions stamps Aug. 12 in three se-tenant (side-by-side) pairs featuring highlights of the industrial revolution and a souvenir sheet of four stamps honoring milestones of the electrical revolution.

Royal Mail worked closely with historian Barrie Trinder to develop the Industrial Revolutions stamps. Trinder is the author of Britain’s Industrial Revolution: The Making of a Manufacturing People, 1700–1870 and many other books focused on industrial developments, according to Royal Mail.

Royal Mail unveiled the designs of the Industrial Revolutions stamps on Aug. 3. “This stamp issue celebrates the ingenuity and pioneering spirit behind some of the most notable inventions and scientific and engineering advances that enabled these ‘Industrial Revolutions’ to take place,” Royal Mail said.

The six stamps in se-tenant pairs name the development being honored in the top left corner, with a brief description and the name of the inventor at lower left.

The first of the two nondenominated (66 pence) second-class stamps honors the Bessemer process, which enabled production of steel on a large scale. The process is named for its inventor, Henry Bessemer (1813-98).

Bessemer “discovered that blowing air through molten iron produced a violent exothermic reaction, and that the resultant metal, subsequently called mild steel, had most of the properties of wrought iron and could be produced on a large scale,” according to Royal Mail.

Bessemer patented his method of producing steel in 1856. It was used extensively until the 1980s.

The rotative steam engine developed by James Watt (1736-1819) is featured on the other second-class stamp.

Watt partnered with Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) of the Soho Manufactory in Birmingham, England, and the first steam engines were completed in 1776. Later advances included Watts’ double-acting engine of 1782, in which steam moved the piston in both directions.

The first successful steam railway locomotive, the Penydarren locomotive developed by Richard Trevithick (1771-1833) in 1804, is honored on one of the two nondenominated (85p) first-class stamps.

In February 1804, the Penydarren locomotive pulled a 10-ton load of iron and approximately 70 men over a distance of 9 miles.

Royal Mail notes that this achievement “was the first documented demonstration that a steam engine could travel on iron rails and pull a load.”

James Hargreaves (circa 1720-78) is credited with producing the first useful spinning machine that employed more than one spindle around 1764. This innovation, commonly called the spinning jenny, is celebrated on the other first-class stamp.

“The machine came to be known as a spinning ‘jenny’, probably derived from a dialect pronunciation of the word ‘engine’, a term that commonly meant machine,” Royal Mail said.

The spinning jenny sparked increases in yarn productivity and was used in some areas of the textile industry for 100 years after it was developed.

Lombe’s silk mill and Portland cement are commemorated on the pair of £1.70 Industrial Revolutions stamps.

The five-story silk mill named after John Lombe (1693-1722) and his half-brother Thomas Lombe (1685-1739) helped revolutionize the process of silk throwing, which involves the cleaning of skeins (loose coils) of silk and then winding them onto bobbins.

Royal Mail describes Lombe’s silk mill as “the first successful water-powered, multistorey textile factory in the United Kingdom.”

Joseph Aspdin developed Portland cement in 1824. It is similar to Portland stone, for which it is named.

Joseph Bazalgette (1819-91) used Portland cement to construct London’s labyrinthine network of sewers because he “was convinced that it was essential if the sewers were to work efficiently and be long-lasting,” according to Royal Mail.

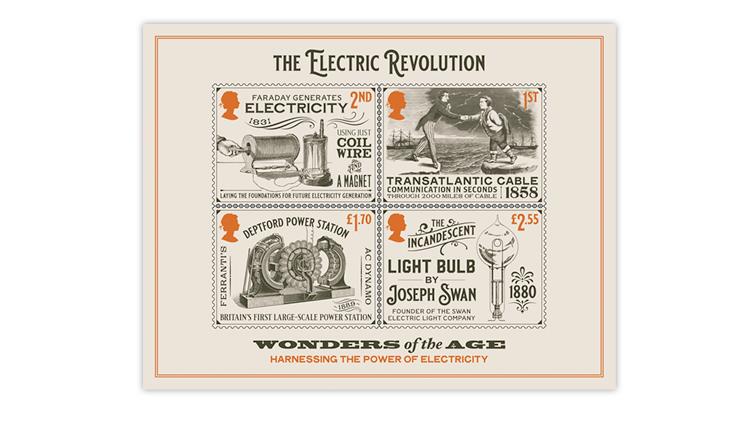

The accompanying souvenir sheet of four celebrates key developments in the electrical revolution. “The Electric Revolution” is printed in the selvage at top, and “Wonders of the Age” and “Harnessing the Power of Electricity” appear in the bottom selvage.

British experimenter Michael Faraday’s landmark 1831 generation of electricity using only a coil wire and a magnet is honored on the second-class stamp at top left. Faraday’s device is prominently featured in the design, and his accomplishment is summarized across the bottom of the design, “Laying the foundations for future electricity generation.”

The first-class stamp at top right recognizes the laying of the first trans-Atlantic cable in 1858. Two individuals are seen shaking hands, symbolizing the cable connection between the United States and Great Britain. “Communication in seconds through 2000 miles of cable” is printed at the bottom of the stamp.

The early failure of the 1858 cable prompted an investigation that eventually led to improved procedures (including the use of common electrical units of measurement) and the laying of the first successful trans-Atlantic cable in 1866.

Britain’s first large-scale alternating current power plant, the Deptford Power Station, is celebrated on the £1.70 stamp at bottom left.

Sebastian de Ferranti (1864–1930) constructed the plant at Deptford in London during 1888-89. The plant’s “two generators and two 1,500-horsepower steam engines were subsequently replaced by turbines of the kind developed by Sir Charles Algernon Parsons (1854–1931),” Royal Mail said.

Joseph Wilson Swan’s development of the incandescent light bulb in Great Britain is commemorated on the £2.55 stamp at bottom right. The stamp pictures an image of Swan’s light bulb at right. An inscription at bottom left states he is “the founder of the Swan Electric Light Company.”

Royal Mail observes that Swan (1828-1914) received a patent for his light bulb in 1880 and “opened a factory in Newcastle-upon-Tyne to make bulbs that soon afterwards lit up the Savoy Theatre in London.”

Common Curiosity, a design firm based in Birmingham, England, designed the six Industrial Revolution sheet stamps and the Electric Revolution souvenir sheet of four, using photographs and drawings from various sources.

International Security Printers printed all 10 Industrial Revolutions stamps by lithography. The six Industrial Revolution stamps, issued in sheets of 60 (sold in panes of 30 at most postal outlets), measure 60 millimeters by 30mm and are perforated gauge 14.5.

The Electric Revolution souvenir sheet of four is 115mm by 89mm, perforated 14.5 by 14.

All 10 Industrial Revolutions stamps are moisture-activated with PVA gum, according to Royal Mail.

Royal Mail is offering other products in conjunction with the Industrial Revolutions issue, including first-day covers, a set of 11 postcards reproducing the designs of the stamps and the souvenir sheet, and a presentation pack with the stamps and the souvenir sheet and information about the processes and inventions they depict.

Also available is a 24-page prestige booklet that includes three panes of four Industrial Revolutions stamps, a pane of eight Queen Elizabeth II definitives with a central label picturing Swan’s incandescent light bulb, and descriptive text by historian Trinder.

The Industrial Revolutions stamps and related products are available online from Royal Mail.

Ordering information also is available from Royal Mail, Tallents House, 21 S. Gyle Crescent, Edinburgh, EH12 9PB, Scotland. Royal Mail’s agency in the United States is Interpost, Box 400, Hewlett, NY 11557.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers

-

World Stamps

Oct 5, 2024, 1 PMCanada Post continues Truth and Reconciliation series