World Stamps

RPSL issues new certificate for 1¢ Magenta

The legendary 1¢ Magenta of British Guiana, one of the world’s rarest and most famous postage stamps, has had its authenticity reaffirmed by the Royal Philatelic Society London.

Sotheby’s, the firm that will offer the stamp in a special New York City auction on June 17, announced the step March 24.

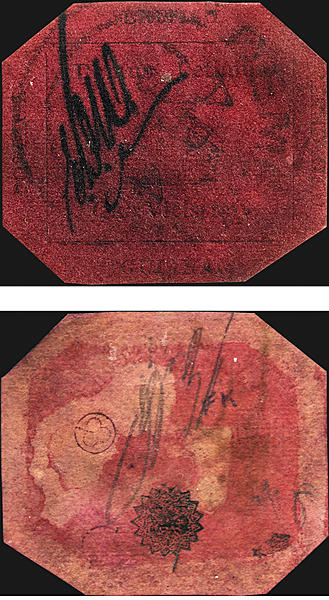

And in a move that is sure to please stamp collectors, Sotheby’s also released an image of the stamp’s reverse side, something philatelists have long wanted to see. The reverse, with its odd coloration and who’s who of owner’s marks, is in some ways more fascinating than the front of the stamp.

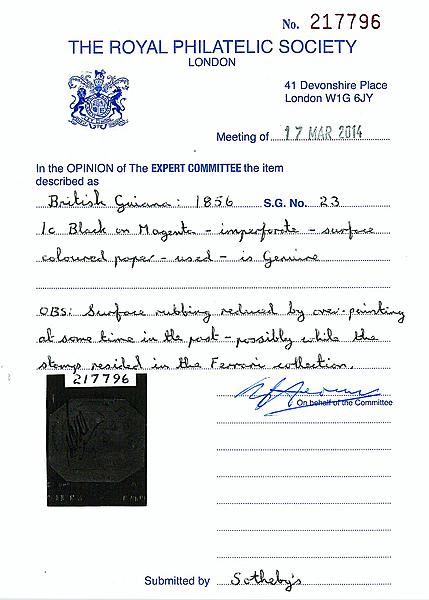

The authentication of the unique stamp, which dates from 1856, took place at a special meeting of the RPSL expert committee on March 17.

The certificate, number 217796, was prepared the same day.

In typical, telegram-like terseness, it states simply, “British Guiana: 1856 — S.G. 23 — 1c black on magenta — imperforate — surface coloured paper — used — is Genuine.”

“S.G.” refers to its listing in the Stanley Gibbons catalog. In the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue, the number is 13.

David Redden, a vice chairman at Sotheby’s in New York, said that although its provenance is not in question, the firm took the step of recertifying the stamp because potential buyers would expect an ironclad guarantee.

“It’s good practice,” he said in a telephone interview March 26. “Technologies change, and there’s more experience” than the last time the stamp was certified in 1935, also by the RPSL.

Since then, the stamp has been owned by famous collectors, investors and most recently, by one of the wealthy heirs to the du Pont family fortune, John E. du Pont, who bought the stamp in 1980 for $935,000, including a 10 percent buyer’s premium.

In the 1990s, while the real thing was locked away in du Pont’s safe, an item purported to be a second example of the 1¢ Magenta surfaced. It was examined twice by the RPSL and pronounced bogus, with the committee finding it to be an altered example of a British Guiana 4¢ stamp of the same issue.

Redden was present at the recent RPSL meeting.

Though the committee has “volumes and volumes” of resource material on fakes and forgeries, they do lack one thing: another genuine example to compare this stamp to.

“It was a very thoughtful process,” Redden recalled. The committee met at the society’s headquarters in a large room housing spectrometers, microscopes and other equipment used to examine “patients” sent in for expertization.

The process of examining the stamp took about five hours. The committee was looking for signs of fraudulent alteration, such as inconsistencies in the paper or the coloration, or physical marks that could be telltale signs of possible fakery. They found none.

The spectrometer readings from different areas of the stamp were identical, Redden said, and no part of the stamp “fluoresced,” or glowed, under ultraviolet light, which could also be a sign of hanky-panky.

Interestingly, the certificate does note “Surface rubbing reduced by over-painting at some time in the past — possibly while the stamp resided in the Ferrari collection.”

This is a reference to one of the stamp’s celebrated past owners, Count Philippe la Renotiere von Ferrary, who owned the 1¢ Magenta from 1878 until his death in 1917. Ferrary bequeathed his collection to the postal museum in Berlin, but the French government seized it as war reparations and sold it in 1922.

Redden said that the conclusion about overpainting comes not so much from anything visible on the surface of the stamp as from the appearance of the reverse.

The paper itself is not magenta-colored. Rather, the magenta color was printed on the surface of the paper prior to the printing of the black design. From the back, however, some magenta ink is visible, in ways that Redden said left committee members scratching their heads.

Part of the magenta color appears almost as a watercolor wash, suggesting that at some point, most likely early in the stamp’s history, someone may have applied a bit of color to the stamp to cover some rubbing of the design.

Redden cautioned, however, that this is conjecture, and he did not want to be seen as speaking on behalf of the committee. (The RPSL could not be reached for comment before this story’s deadline.)

Other possible explanations for the coloration exist, including the fact that the stamp spent the first 20 years of its existence in a humid, tropical environment.

Besides the coloration, the most fascinating aspect of the reverse is the many owner’s marks it displays.

They include two strikes of Ferrary’s trefoil mark; a large, faint H of Arthur Hind, who reportedly outbid three kings to acquire the stamp in 1922; a small FK, from Finbar Kenny, the stamp manager at Macy’s department store who brokered its sale by Hind’s widow; a small shooting star applied by Frederick Small, who owned the stamp from 1940 to 1970; a penciled IW belonging to Irwin Weinberg, head of an investors’ consortium that acquired the stamp in 1970; and last but not least, a large J E d P, the initials of its most recent owner.

Some of the marks are upside-down, perhaps because the stamp was flipped up while hinged onto an album page. A trace of a removed hinge can be seen at top.

There is also an ornate, 17-pointed star that left the committee stumped. It does not resemble any known owner’s or expert’s mark, and the question of who applied it and when remains a mystery.

Redden said a well-respected paper conservator at Sotheby’s had seen the stamp. She offered no formal opinion, other than to say that the stamp seems remarkably well-preserved for its age. n

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

Postal Updates

Oct 7, 2024, 5 PMUSPS plans to raise postal rates five times in next three years

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available