World Stamps

The ‘rainbow trials’ and how the Penny Black was replaced: Great Britain Philately

By Larry Rosenblum

The year 1840 must have been one of both elation and frustration for Rowland Hill. After years of struggle, the postal reform that he and others had campaigned for in Great Britain was finally enacted. The plan included both a drastic decrease in postal rates and the beginning of a change from the recipient to the sender paying postage.

Hill had developed two ways for the sender to prepay postage: official postal stationery and postage stamps that could be applied to ordinary envelopes.

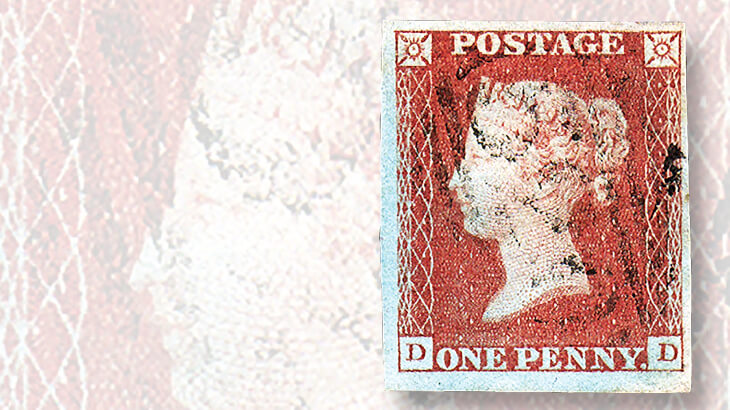

The stamps, known as the Penny Black and the Two-Penny Blue (or Tuppenny Blue), were masterpieces of design and printing, but problems were developing even before they came into use.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Each stamp was to be defaced with a red cancel when processed so that it could not be used again. Before the stamps came into use on May 6, 1840, there was disagreement about whether the red cancel could be easily removed.

It wasn’t long before such fears were justified. On May 21, Hill wrote, “all sorts of tricks are being played by the public who are exercising their ingenuity in devising contrivances for removing the obliterating stamps [cancels] by chemical agents and other means.”

Hill immediately began work on the problem along with chemist Richard Phillips, the printer Joshua Bacon (of Perkins, Bacon & Petch), and others.

Bacon produced a special plate of three impressions of the 1d die to be used for testing. The upper-right corner of the images was covered in wax so that the printed examples could not be used for postage.

When three images proved to be insufficient for testing, a new plate of 12 examples was made. This was used to print test stamps in many colors. These experiments, which lasted until late December 1840, have been known as the “rainbow trials” since 1863.

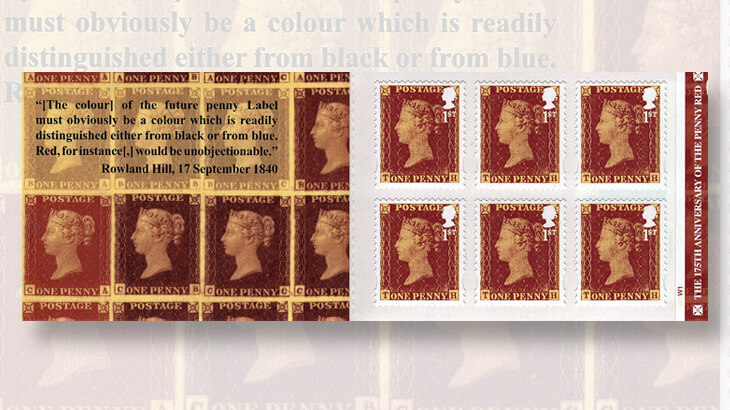

As part of its celebration of the 175th anniversary of the Penny Red, Royal Mail issued a special commemorative sheet Feb. 17 with 20 of the reissued Penny Red stamps and 10 different images of rainbow trials.

The background shows a presentation sheet created by Joshua Bacon’s son Perkins on Aug. 31, 1840. Perkins’ sheet includes 20 different red colors, some of which are crossed out because they were already determined to be unsuitable.

A good solution to the problem was fairly obvious early on. A helpful member of the public, Thomas Brighouse, wrote to the Treasury on May 10 about the removal of cancellations and suggested, “The new stamps would be better printed in light red and light blue and defaced with black ink.”

Hill was already leaning towards red, but he wanted to determine the best shade, so trials were conducted in various shades of rose, red, and brown.

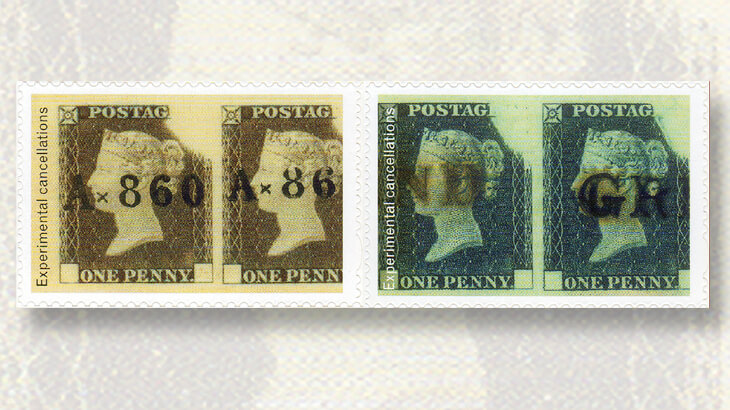

Various handstamps were used to test the effectiveness of canceling inks.

At first, readily available handstamps were used. The Royal Mail sheet shows one that printed “Ax860” and parts of another that printed “GRIND.” The latter stamp was filed down from “GRINDLAY & CO,” a bank.

Later, special handstamps were created with concentric circles and with the Maltese cross design in use at the time.

Many experiments involved a chemical then called prussiate of potash, now called potassium ferrocyanide.

This chemical would make the red ink of the stamp more fugitive, that is, destroyed by any substance that might be used to remove the cancel.

A side effect, however, was that when prussiate of potash combined with water (as it would be when the paper was dampened for printing), it would turn the paper blue.

Prussiate of potash was tested in three different ways: incorporation into the paper, incorporation into the red printing ink, and dipping the printed stamp into a solution of the chemical.

The Royal Mail sheet shows the result of one of these tests. However, the inscription on the sheet, “Pink on blue paper trial,” is incorrect. The image is a pink stamp printed on white paper that was subsequently dipped in a prussiate of potash solution.

Eventually, some prussiate of potash was incorporated into the ink used to print the Penny Red. Some stamps have so much of this chemical that the paper has turned blue in the areas where the red ink is heavily applied but remains white where the red ink is light, primarily the queen’s portrait.

These stamps are called “ivory heads” because the portrait area appears as an ivory color when the back of the stamp is viewed.

This bluing was eliminated in 1857 by a change in the formula of the ink.

By September, Hill had chosen the red color and made good progress on the composition of a suitable black ink for cancellation.

An excerpt from Hill’s first report to his boss, Francis Baring, chancellor of the exchequer (head of her majesty’s Treasury), was reproduced in the stamp booklet issued Feb. 17 containing reissued Penny Red stamps: “(The colour) of the future penny Label [postage stamp] must obviously be a colour which is readily distinguished either from black or from blue. Red, for instance, would be unobjectionable.”

With the penny stamp pretty much settled, efforts turned to the blue 2d stamp. It had already been decided that the blue color was satisfactory with a black cancel, but efforts were made to find a more fugitive ink.

Besides shades of blue, Hill tested some green colors. These were discarded as unattractive and too easily confused with black under candlelight.

Eventually a new formula was found with the same color as the existing stamps. To differentiate this version, horizontal white lines were added to the design. Some 2d stamps also have ivory heads.

A transition plan was developed. The new black ink would be used as soon as possible, while the new stamps would not be issued until stocks of the old ones were almost used up. Therefore, the original Penny Black and Two-Penny Blue can be found with black Maltese Cross cancels.

The Penny Red was issued on Feb. 10, 1841, and the new Two-Penny Blue followed on March 13.

The result of seven months of hard work was two new stamps, new canceling ink, and much better security from fraudulent reuse of postage stamps.

More about the Penny Black:

Great Britain’s Penny Black evolved into many colors

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers