World Stamps

Romania’s 1906 semipostals reflected queen’s interests

By Kathleen Wunderly

The world’s first semipostal stamps, with a surcharge (beyond the cost of postage) that was designated for a charitable purpose, were issued in New South Wales and Victoria in 1897. Romania, however, was not too far behind, becoming the first European country to issue semipostals, in 1906.

Between January and August in that year, four sets containing four stamps each were issued. Each set has a common design, and each set also has the same four denominations: 3 bani+7b; 5b+10b;10b+10b; and 15b+10b.

The first set, Scott B1-B4, was issued Jan. 14, 1906; the second, B5-B8, on March 18; the third, B9-B12, on March 23; and the last set, B13-B16, on Aug. 4. The shared feature among the four sets of stamps is Romania’s Queen Elizabeth, consort of King Carol I.

Slightly smaller than the state of Oregon, Romania is in southeastern Europe, at the northern end of the Balkan peninsula. The name “Romania,” meaning “New Rome,” was used officially in 1859 when the regions of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania united, but the name was used during the Roman colonization of the ancient province then known as Dacia in the first century.

The country over time was occupied by the Goths, Slavs, Greeks, Hungarians and Turks, but the inhabitants managed to maintain their mother tongue, which is a Romance language. In 1878 Romania won full independence from the Ottoman Empire by treaty, and became a kingdom in 1881, with Carol I and Elizabeth crowned as the first monarchs.

The country name in the native language is Romania (and that is what appears on its postage stamps), but over time it has been spelled in English as Romania, Rumania or Roumania.

Elizabeth (1843-1916) was not a mere royal placeholder, but an interesting and progressive woman. She was born in the principality of Wied in northeastern Germany to a prince and a duke’s daughter. Artistic, musical, gifted with languages, and deeply drawn to literature, Elizabeth began writing poetry at the age of 16. She adopted the pen name “Carmen Sylva” (derived from the Latin words for song and forest), referring to her love of both music and the woodlands of her birthplace.

She met Charles of Hohenzollern, Prince of Romania, in 1861 and married him in 1869. The German princess immersed herself in the people and culture of her new homeland, quickly learning the language. Elizabeth admired Romanian crafts and costume and often wore traditional folk clothing, making it a fashion for the upper classes.

Elizabeth did not remain aloof, imitating the clothing of the people but otherwise ignoring them. Today she would be known as a hands-on leader.

In 1871, she founded her first charitable society, distributing lavish quantities of fuel annually to the poor. She gave funds to begin a school of embroidery, to teach peasant girls to read, write and embroider in the Romanian traditional style. Having made folk dress stylish, Elizabeth then encouraged her friends to buy the embroidered products.

Meanwhile, as Carmen Sylva, Elizabeth continued to write and publish, producing more than a thousand poems, dozens of novels, and numerous translations of Romanian and other literary materials. Romania Scott 206 from 1906 depicts her standing at a writing desk, pen in hand.

All was not just folklore and poetry for Elizabeth, however. The Russo-Turkish wars were a series of conflicts between the Russian and Ottoman empires extending from 1568 to 1923, but the Russo-Turkish War that directly affected Romania took place in 1877-78. Elizabeth was personally involved in caring for the wounded, and funded a hospital in the park of the royal palace in Bucharest. Her compassion during the war earned her the affectionate name “Mama Ranitilor” (Mother of the Wounded) from the people.

Other personal causes were an organization that translated children’s books into Romanian; a society called Albian that provided “rough” sewing work to poor women, such as making tents and clothing for soldiers; and a society called Concordia that encouraged native industry, especially schools that taught students to weave linen from native hemp.

Elizabeth also founded what one of her biographers called a “large charitable association,” Societe de Bienfaisance, seemingly of more general intent than her other groups with specific focus.

All of the 1906 semipostal issues are customarily referred to in the philatelic literature as benefiting “the welfare fund,” but considering Queen Elizabeth’s various causes, and how they could relate to the designs on the stamps, it seems possible that the sets of stamps were intended to finance specific charitable enterprises.

The first quartet, Scott B1-B4, shows Elizabeth at a spinning wheel, wearing Romanian traditional dress. A photograph very similar to this stamp design appears in some biographies of Elizabeth. At the foot of the vignette is an irregular oval containing a sentence in Elizabeth’s handwriting, with her signature, a motif that is carried through all four sets of stamps, but with a different “motto” for each set.

The sentence for the spinning set translates as “God guide our hand.” The vertically-oriented stamps were printed by typography on unwatermarked paper at the Government Printing Works in Bucharest, perforated either gauge 11½ or 11½ by 13½.

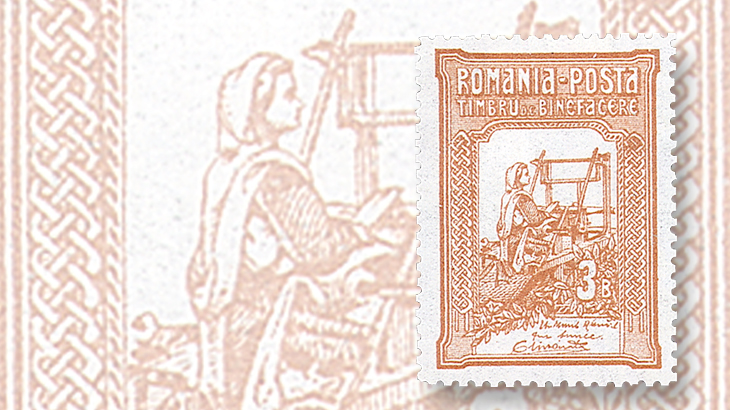

The queen is shown weaving on the second set of stamps, Scott B5-B8, and the quotation in the design is “Woman weaves the future of the country.” These vertical issues have the same specifications as the first set as far as printing, paper and perforations.

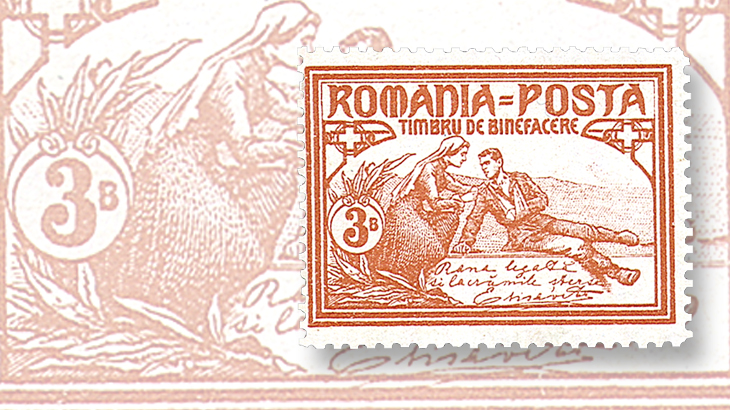

The queen is depicted nursing a wounded soldier on the third group of stamps, Scott B9-B12, with the quotation, “The wounds dressed and the tears wiped away.” Typographed on watermarked paper, these stamps are oriented horizontally and perforated gauge 11½ or 13½ by 11½.

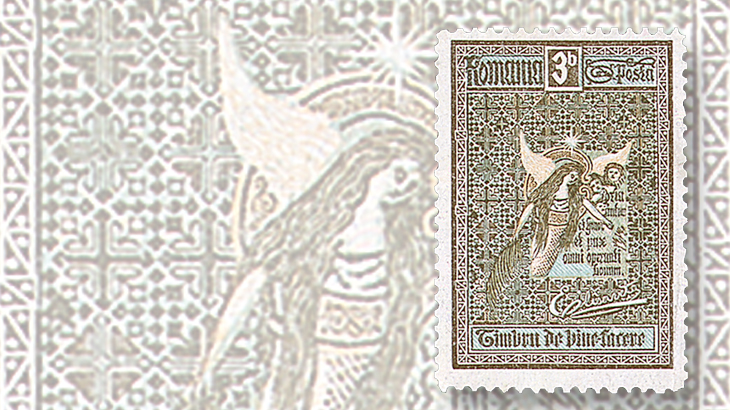

The last set in the 1906 semipostals, Scott B13-B16, is in elaborately art nouveau style, with lavish ornamentation surrounding a large angel hovering over either a child or a cherub, accompanied by the saying, “But glory, honor and peace to all that do good.” These stamps were typographed by Bradbury Wilkinson & Co. in London on unwatermarked paper perforated gauge 12.

The Scott Classic Specialized Catalogue of Stamps and Covers 1840-1940 notes that booklet panes of four exist of Scott B1-B3, B5-B7 and B9-B12. The catalog also warns that “counterfeits of B1-B12 are plentiful,” and “plentiful” may be an understatement. A collector wrote to Stamps magazine of Dec. 30, 1939, warning that forgeries of the 1906 semipostals “are being offered quite freely from Europe.” A series of articles in 1949 in the S.P.A. Journal detailed the differences between genuine and fake examples of the stamps, and called the issue “extensively counterfeited and frequently found,” with counterfeits “very common,” in both mint and used condition.

John Barefoot and Andrew Hall documented the 1906 charity issues in their 16-page forgery and reprint guide published in 1983.

The Scott Classic specialized catalog values Romania Scott B1-B4 (queen spinning) at $61 mint and $26 used, with the same valuations for B5-B8 (queen weaving) and B9-B12 (queen as war nurse), for a total of $183 for all three sets mint and $78 used. The angel quartet, B13-B16, is valued at $24.50 mint and $9.75 used.

Collectors in 1906 complained bitterly in the philatelic press of being exploited by this mass of charity stamps, but if Queen Elizabeth’s favorite causes were the recipients of the profits, the compassionate monarch probably felt no remorse at all about the situation.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers