World Stamps

Small Queens of Canada: How one sale showcased the stamps’ many usages

By Fred Baumann

I am fascinated by 19th-century Canadian stamps. Their beauty beguiles beginners young and old, while their almost infinite differences make them an inexhaustible challenge to advanced hobbyists.

As an article on the website Stamp Collecting World accurately notes — (with parenthetical commentary by its author) — “Collecting these stamps can be as simple (and inexpensive) or as complex (and tremendously expensive) as the collector desires.”

Canada’s Small Queen stamps of 1870-97 are special favorites. Used examples of the common lower denominations are easily affordable, while some of the rarest multiples and usages are unique.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

According to Daniel Cantor, one of the foremost Canadian philatelists of the last century, “The issue has much to fascinate the serious collector: the great range of collectible varieties, the different printing periods, various perforation measurements, colours and papers.”

If Cantor’s name seems familiar, you may be experiencing a bit of Linn’s deja vu. Less than a year ago, associate editor Michael Baadke previewed Sparks Auctions’ sale 19 of the Daniel Cantor Collection of Canada Small Queens in November 2015, and New York correspondent Matthew Healey followed it with a summary of results in December.

The catalog for this Nov. 24 sale is available online at the Sparks Auctions website for your perusal. All prices realized for selected lots that follow include the buyer’s premium.

Where did the Large and Small Queens come from? The answer, as with so much Small Queens technical detail, may be found in The Small Queens of Canada by John Hillson: “The design was based on an essay submitted by the British security printing firm of Bradbury, Wilkinson & Company of London, which showed the portrait of the young Queen Victoria facing to the right, instead of to the left, which was more normal.”

This right-facing orientation was retained in the first postage stamps I am aware of to have used this portrait — low denominations printed by the American Bank Note Co. in New York for use in the colony of Nova Scotia in 1860, including the 1¢ black (Scott 8).

Hillson continued: “The vignette was engraved by Mr. Alfred Jones … from a similar work by the English engraver Mr. Charles Henry Jones. The lettering was executed by Mr. Henry Earle, Sr., and it is believed that the ornamental scroll work was done by the president of the British American Bank Note Co., Mr. William C. Smillie.

“When the size of the stamps was reduced from the Large Queen Series, the vignette rim became tighter, but the actual portrait size was not reduced.”

Others have pointed out that the portrait on the smallest of the Large Queens, the ½¢ denomination (Scott 21) was virtually identical in appearance to that of the Small Queens, including the 1¢. A trial plate proof in black of the 1¢ from the Cantor sale is shown nearby.

I want to concentrate on that 1¢ denomination, a humble workhorse in the Small Queens stable.

Perforated 12, it was issued in yellow (Scott 35) and in orange (35a), which is scarcer, in 1870, and in a still scarcer perf 11½ by 12 orange version in 1873 (35d).

As former Linn’s editor and publisher Michael Laurence told me many years ago regarding his amazing collection of United States 1869 10¢ Pictorials, classic issues in yellow may lack the visual authority of stronger colors, diminishing their appeal to some collectors, but few colors show off postmarks so well.

Before we look at rare and unusual 1¢ Small Queens, I’d like to show you some less uncommon and refreshingly affordable usages from the Sparks sale that I’d be delighted to own.

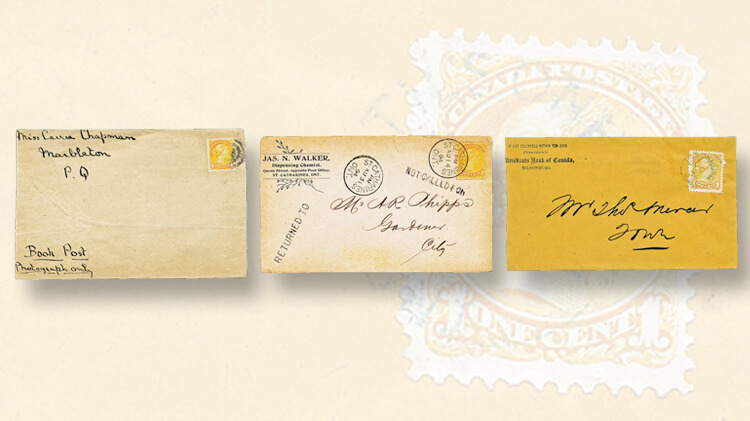

Shown nearby are three covers from a balance lot of 15 used to Canada and the United States — covers well worth having but not valuable enough to auction individually. Such balance lots can be a great resource for those getting started in postal history.

This trio includes a Quebec cover with a three-ring mute cancel correctly paying the 1868 1¢ book post rate; an undeliverable 1894 local commercial drop letter handstamped “NOT CALLED FOR” and “RETURNED TO” a pharmacist in St. Catharines, Ontario; and a bank envelope drop letter with the 1¢ stamp neatly tied by a blue split-ring July 2, 1874, date-stamp mailed in Tillsonburg, Ontario. Estimated at $500, the 15-cover lot sold for $345, which equals $23 per cover.

Ian Kimmerly, president and auctioneer of Sparks Auctions in Ottawa (though he now enjoys the more salubrious winters of Victoria, British Columbia), is a veteran Canadian philatelist, having served as collector, exhibitor, dealer, auctioneer, stamp columnist, and stamp club president. He joined the American Philatelic Society at age 14 and has been learning about the hobby ever since.

It is through Kimmerly’s generosity that the images here have been made available for this column.

He also shared some of his insights from the preparation of the sale: “There are dozens of rates available for just the 1¢ value. During the 27 years of its use there are many classes and sub-classes of mail, different charges by weight and by destination and then administrative changes of these rates during the period.

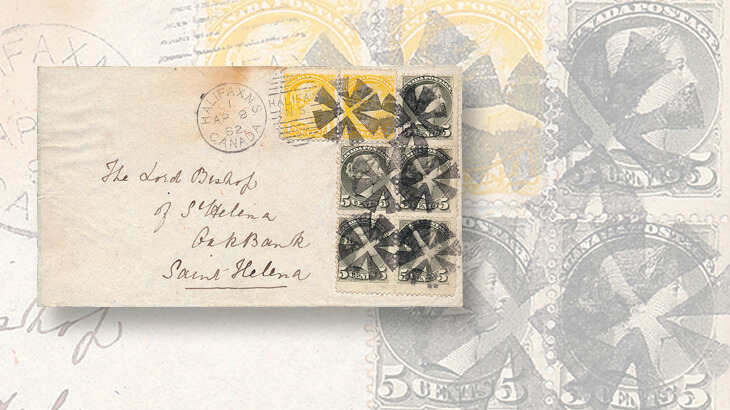

“The highest price for a cover with 1¢ values was one to St. Helena with a pair together with five 5¢ values — a 27¢ rate — which realized $12,650.”

Addressed to the Lord Bishop of the remote Atlantic island, the stamps were strikingly canceled with a cut cork wedge device and a Halifax duplex datestamp on the 1¢ pair.

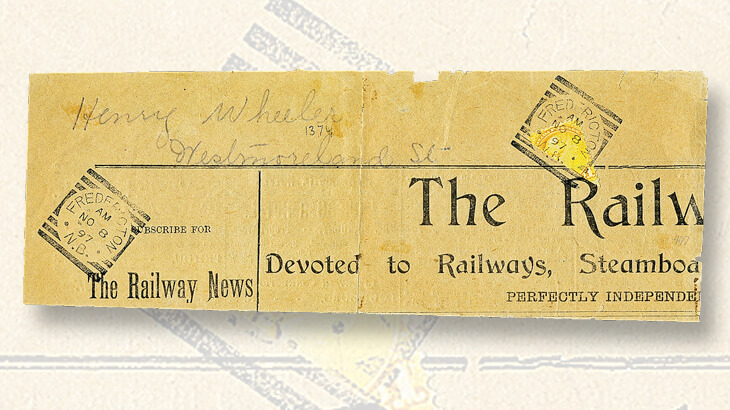

“For items with only the 1¢, the record went to a diagonal bisect on large piece paying the domestic second-class rate for transient newspapers, which realized $7,130,” Kimmerly said.

This rare use (Scott 35c) on the masthead of the Railway News was authorized by the Canadian post office at Fredericton, New Brunswick, between Nov. 5 and 8, 1897, when no ½¢ stamps to correctly pay the rate were available. Ex-Dale-Lichtenstein, this is one of only six legitimate examples known.

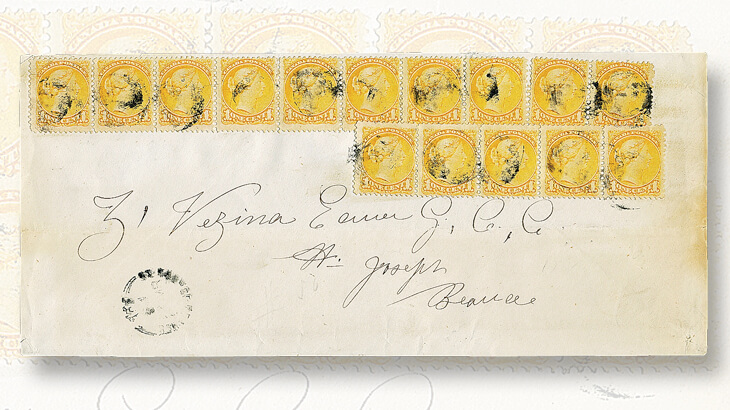

At the other extreme of 1¢ usages is “a large envelope paying the quintuple domestic rate with fifteen 1¢ stamps. This was estimated at $200 but was knocked down for $172.50,” Kimmerly said.

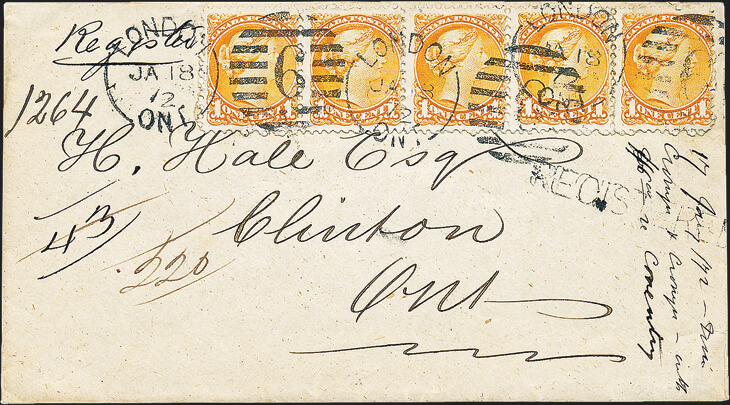

He also remarked on two 1871 covers both bearing five 1¢ stamps, paying the domestic rate of 3¢ plus 2¢ registration: “The one with two pairs and a single in the red orange shade (Unitrade 35iv) realized a respectable $345, but the other with a strip of five in yellow orange on thick soft paper was aggressively bid up to $4,600.”

A striking 1¢ rarity, as yet unrecognized in both the Scott and Unitrade catalogs, found its place in the sun as well — a used single with a clean segmented cork cancel showing a complete double impression of the entire design. It better than tripled its $3,000 presale estimate, hammered down at $9,200.

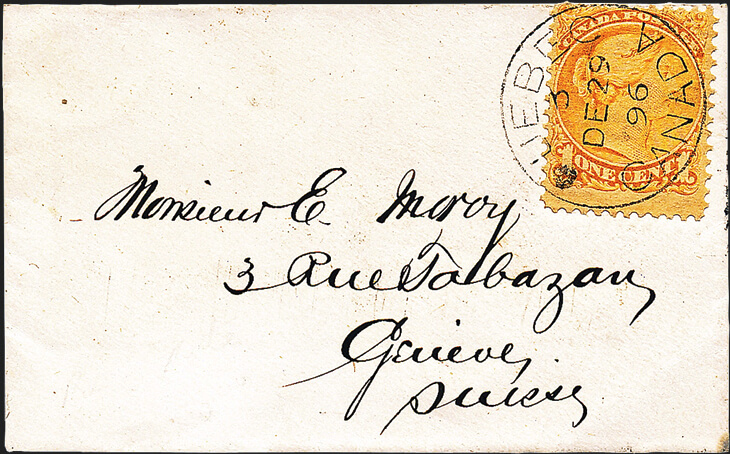

There were two items I was particularly fond of in this auction, as were their winning bidders. The first was a handsome 1¢ yellow single franking on a tiny 1896 Universal Postal Union third-class printed-matter rate cover from Quebec City to Geneva, Switzerland. Estimated at $150, it soared to $661.

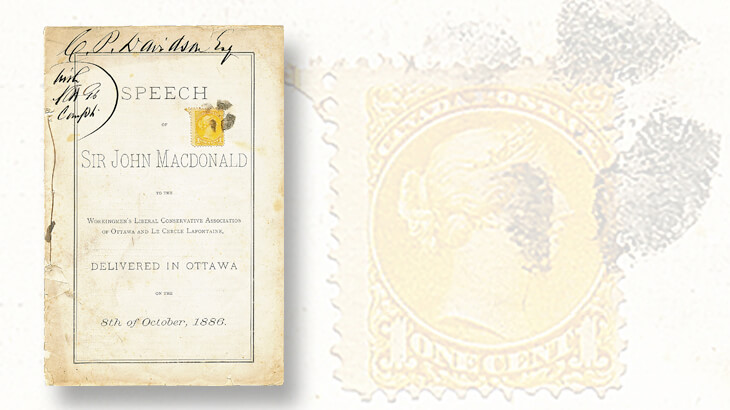

But I saved the best, another single franking, for last. I can’t disagree with the auction catalog description of it as perhaps “the most exceptional domestic use of a single 1¢ Small Queen.” It is a cork-canceled 1¢ used in 1886 to pay the third-class rate on a pamphlet less than 4 ounces from Ottawa to Durham, Ontario.

It’s the content that makes this item a gem: a 23-page copy of a speech by Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, then in the last of his unequalled six majorities in power, to the “Workingman’s Liberal Conservative Association of Ottawa.” Offered at $750, it found an owner who deserved it at $2,530.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers