World Stamps

Stamps honoring good science may sometimes display bad design

By George Wistreich

Microbiology is a dynamic and highly diverse science. It includes the study of viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa and certain algae.

Most general texts dealing with the science also include the study of worms (because of the ability of these forms of life to cause disease) and the study of the immune system, which covers approaches to disease prevention and diagnosis and related topics.

Being so diverse in its scope, microbiology offers numerous subjects as potential topics for stamps, ranging from scientific discoveries to diseases and their transmission.

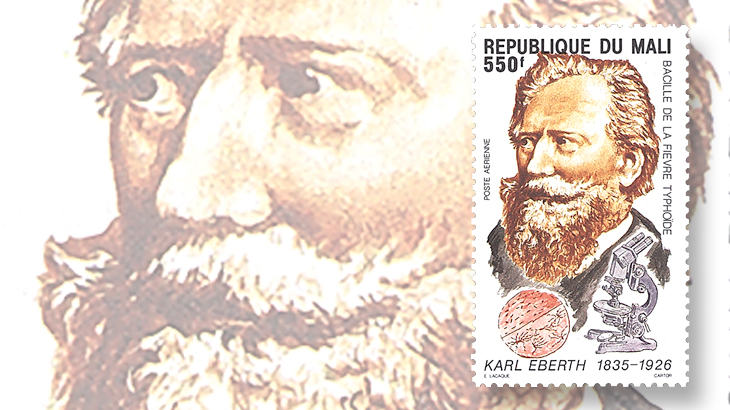

Most such stamps are accurately presented and sometimes quite detailed. One example, shown here, is the Mali issue of June 7, 1986, showing the German bacteriologist-pathologist Karl Eberth (1835-1926), the discoverer of the bacterial cause of typhoid fever.

The 550-franc stamp (Scott C523) presents a portrait of the bacteriologist together with a microscopic view of the bacterium first referred to as Eberthella typhi and later renamed Salmonella typhi.

While this stamp is a good example of an accurate representation of scientific information, there are some stamps that are unfortunately inaccurate or incomplete. Here are a few examples of design errors on microbiology topical stamps.

The illustrated 20¢ Transkei stamp issued Oct. 5, 1982 (Scott 98), depicts a portrait of Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a somewhat modern version of a compound microscope and the subtitle designation of “father of the microscope.”

Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), a rather well-to-do tradesman and a dry-goods merchant, also was an amateur lens grinder. He was skillful at grinding single pieces of blown glass into fine magnifying lenses.

Individual lenses that had a thickness of about 1 millimeter were placed into holes of two small thin metal plates (usually brass) that were riveted together, thus forming a simple (one-lens) microscope.

Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes could easily be held in one hand and generally measured about 2 inches in length and 1 inch across. Depending upon the quality of the lens used, magnifications ranged from 70x to more than 250x.

The microscope shown on the Transkei stamp is not of the type crafted by Leeuwenhoek, but rather is a compound instrument, which is generally credited to Hans and Zacharias Jenssen.

In 1590, the Jenssens introduced a second lens, which formed the basis for the principle on which later compound microscopes are based.

Leeuwenhoek continued making better microscope lenses and making numerous observations of microorganisms and other types of biological specimens.

Because of his early observations and sketches of bacteria and protozoa, he is commonly considered to be the “father of bacteriology and protozoology.”

When anesthetics were introduced into surgery and obstetrics during the 1840s, surgeons began performing longer, more complex procedures. Unfortunately, the number of surgical wound infections increased at the same time, often causing the death of patients.

Hospitals practiced surgery under unsanitary conditions. Moreover, surgeons of the time often took pride in the accumulated surgery-related stains on their unwashed operating gowns, as an indication of their surgical expertise.

The young English surgeon Joseph Lister (1827-1912) undertook the study of preventing wound infections. Impressed with the studies of the French scientist Louis Pasteur, which demonstrated the involvement of microorganisms in the processes of fermentation and putrefaction, Lister reasoned that surgical infection, or sepsis, might actually be caused by microbes, and he developed techniques designed to prevent access of microorganisms to wounds.

Lister’s approach, which became known as antiseptic surgery, included the application of carbolic acid (phenol) to wounds by means of dressings, and his own invention of a spray device for administering phenol during a surgical procedure in the operating room.

Lister also instructed surgeons to wash their hands in carbolic acid solutions before and after operations, and to wear clean gloves during surgery.

Instruments also were to be washed in the same type of solution, and thus carbolic acid became the first widely used surgical antiseptic.

The pathogenic bacterial cause of listeriosis (the third leading cause of human food-borne infections), namely Listeria monocytogenes, and the well-known antiseptic mouthwash, Listerine, were named after Joseph Lister.

The 30¢ Transkei stamp of Oct. 5, 1982 (Scott 100), shown nearby, pictures Joseph Lister and an instrument known as a hemostat, or arterial forceps, in the upper left.

Several individuals are credited with the development of the modern-day hemostat (the foremost of them being Jules-Emile Paen), but Lister is not one of them, even though he no doubt used the surgical tool or some similar type of instrument in performing his operations.

A more appropriate and historically correct object denoting Lister’s contributions would have been his carbolic spraying device.

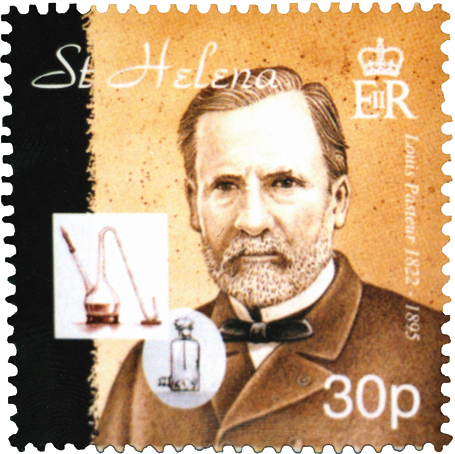

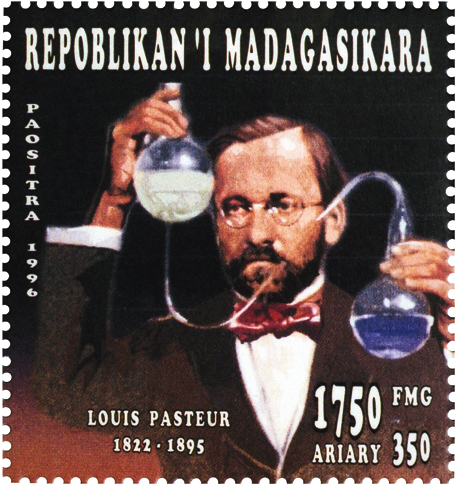

The French chemist and scientist Louis Pasteur (1822-85) is sometimes referred to as the “freelance of science.” He is credited with many significant discoveries, which include uncovering the role of microbes in various fermentations such as winemaking; developing the pasteurization process and the first vaccine for the viral disease rabies; and establishing evidence for the germ theory of disease.

Among the most memorable of his achievements were the experiments he devised to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation.

This theory, stated by the Greek philosopher-scientist Aristotle in 345 B.C., and widely believed as late as the 19th century, held that life could and did appear spontaneously from nonliving or decomposed matter.

People saw what they interpreted as examples of spontaneous generation, such as snakes, frogs, and related forms of life apparently developing from the mud of river banks or maggots appearing in decaying food.

These and related beliefs, held by the majority of Greek scholars, were accepted and expanded throughout the Middle Ages and up until relatively recent times.

Today, the theory of spontaneous generation seems absurd, but it occupied an important place in scientific thought for centuries and stood in the way of demonstrating any relationship between microorganisms and disease.

The spontaneous generation theory had to be disproved, and Pasteur took on the challenge. In order to put an end to the theory, he used exacting, thoughtful and carefully designed experiments.

In one of the experiments (which some have called his most elegant), Pasteur used specially prepared swan-necked or S-shaped flasks.

A correct example of a swan-necked flask is shown on the 1996 1,750-franc Malagasy Republic stamp (Scott 1322), shown here.

An incorrect flask appears on the pictured 30-penny St. Helena stamp (Scott 850) from 2003.

From the earliest of times, many diseases were associated with natural phenomena, supernatural forces and poisonous vapors.

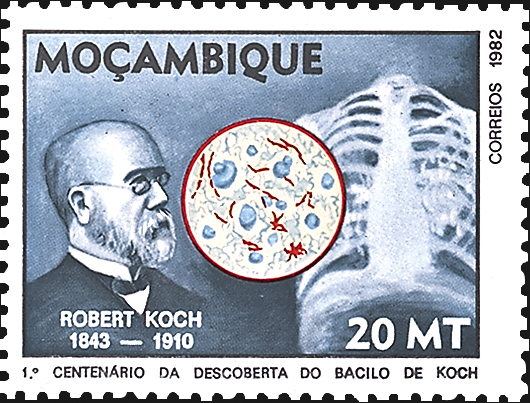

German physician Robert Koch (1843-1910) was among several individuals who established the causal relationship between a microscopic disease agent and a disease. His many contributions included the discovery of the bacterial cause of tuberculosis. This disease has been around for centuries and unfortunately is still a plague of humanity, especially in populations suffering from malnutrition, poor sanitary conditions and other diseases such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

The name given to tuberculosis probably arose from the finding of small patches of infected tissue or tubercles in the lungs of its victims.

Illustrated nearby is a 1982 Mozambique stamp (Scott 811) commemorating the centenary of Koch’s discovery of the cause of tuberculosis.

The design pictures the scientist, a microscopic view of stained bacteria and a skeletal image of the chest known as the thorax. The thorax contains the heart, lungs and other significant body organs. However, on this stamp, the lungs, the main target of tuberculosis, are missing.

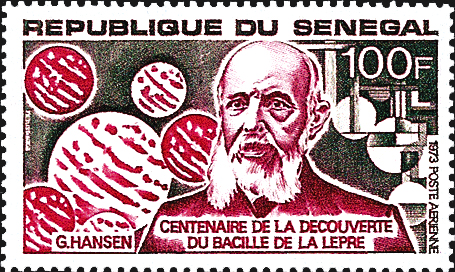

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is named after the Norwegian physician Armauer G. Hansen, the discoverer of its bacterial cause, Mycobacterium leprae.

This bacterial pathogen (also referred to as Hansen’s bacillus) is unusual from a laboratory point of view in that it requires living cells for its reproduction and growth. Thus, it cannot be cultivated on the types of artificial laboratory media (growth preparations) in plates such as those shown in the background of the 1973 100-franc Senegal stamp (Scott C125), issued for the centenary of the discovery of Hansen’s bacillus.

The only way to grow the pathogen is in certain living animals, such as mice and nine-banded armadillos.

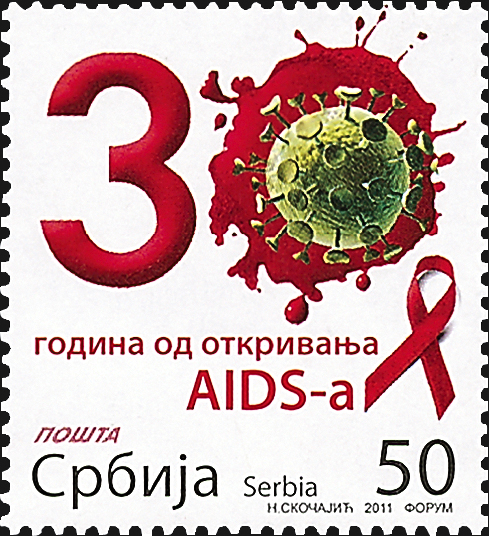

AIDS is a disease of the immune system that results in life-threatening opportunistic microbial infections or cancerous growths. The first cases were reported in mid-1981.

Only three years after AIDS was first described, its cause was shown to be the virus now known as the human immunodeficiency virus or HIV.

The 50-dinar Serbia stamp (Scott 550) shown nearby was issued in 2011 to mark the 30th anniversary of the campaign against AIDS. The design includes the red ribbon associated with AIDS awareness and support campaigns and an electron micrograph in the “0” of “30” of what presumably was supposed to be HIV, but is not.

What is actually shown is an electron micrograph of a cell. HIV has a distinctive appearance that is correctly shown on the 1994 France 2.80-franc stamp (Scott 2419) shown nearby, issued in recognition of the discovery of HIV by researchers (including Luc Montagnier and Francoise Barre-Sinoussi) at the Institut Pasteur in Paris.

Today’s world of instant news and ready Internet access provides what often seems to be an overwhelming accumulation of information about almost anything, including science.

However, the interpretation and use of this information correctly should be of paramount importance — both in the selection of topics and in the design of subjects portrayed on all stamps.

George Wistreich, an author and a former chair of life sciences at East Los Angeles College, collects stamps with an emphasis on science, microbiology and infectious diseases, and the individuals associated with these topics.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers