World Stamps

Stamps trace evolution of Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

By Rick Miller

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, a name expressing more truth than poetry, arose out of the ashes of World War I as a marriage of convenience.

It issued stamps from 1918 until the name of the country was officially changed to Yugoslavia (land of the Southern Slavs) on Oct. 3, 1929.

Serbia and Montenegro had been on the winning side in World War I, but they took a beating. Serbia suffered more casualties as a percentage of population, than any other country in the war.

Connect with Linn's Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

After Serbia and Montenegro were defeated and occupied by the Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian, and German armies in 1915-1916, the Serbian and Montenegrin armies were evacuated to the Western Front, where they continued to fight.

When the Allies launched an invasion of the Balkans through Greece, the Serbian and Montenegrin armies returned as part of the invasion force.

After the war, Serbia expected to be rewarded. It happened that King Peter I of Serbia was the son-in-law of King Nicholas I of Montenegro. King Peter’s son, Crown Prince Alexander, was the grandson of King Nicholas.

King Peter was elderly, and Crown Prince Alexander was already effectively running much of the government. Although Montenegro had been on the winning side, the Allies countenanced Serbia engineering a merger with Montenegro.

King Nicholas and his sons were shunted aside in favor of King Peter and Alexander. It was hoped that because Alexander was the grandson of King Nicholas, the merger would be generally acceptable, but it was not in accordance with the wishes of the Montenegrin people.

Serbia acquired much of Macedonia from its victories in the First and Second Balkan Wars. After World War I, Serbia got much of the rest of Macedonia from Bulgaria, which had been on the losing side.

It was not a happy acquisition, and the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization would carry out guerilla warfare and terrorist attacks and assassination against Serbia for much of the interwar period.

Croatia had been part of the Kingdom of Hungary since 1091, and with Hungary it joined the Habsburg Empire in 1526. Slovenia became part of the Habsburg Empire in the 13th century. Bosnia, which included Herzegovina, was a province of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1878, Austria-Hungary was given the right to administer the province. In 1908, Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia outright, angering both the large Serbian population who lived there and the adjacent Kingdom of Serbia.

Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia had all been relatively loyal parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, contributing troops and support to the war effort.

But as the empire broke apart in 1918, it was clear that the successor states of the empire would be punished by the victorious Allies with loss of territory and reparations payments.

When approached by the Serbians with the possibility of forming one country, all three saw it as an opportunity to change their status from a defeated Central Power to a victorious Ally, so they agreed.

From 1918 to January 1921, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia operated separate postal systems, issued their own stamps, and even used different monetary systems.

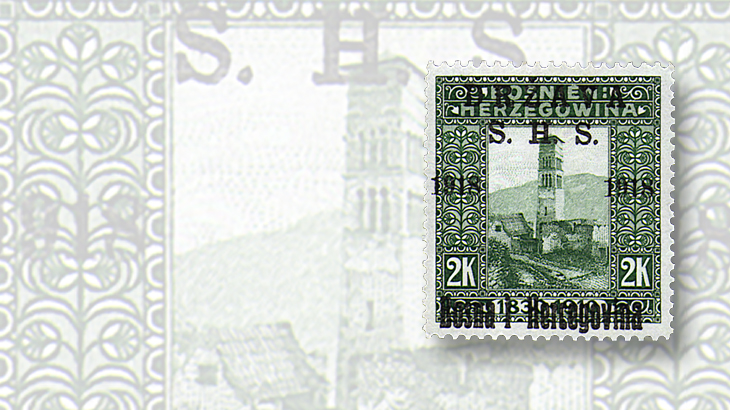

The stamps of Serbia only bear that country’s name, but the stamps of the other three nations bear their own name plus the abbreviation “S H S” for the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia (Hrvatska in Croatian) and Slovenia.

In January 1921, the separate postal systems and currencies were amalgamated into one system, and each country ceased to issue its own stamps.

The general-issue stamps prepared for use throughout the country were inscribed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in Cyrillic and Latin letters and denominated in paras and dinars.

The country was doomed to failure by its inherent contradictions.

The Serbs tended to view the country as Greater Serbia, while the Croats and Slovenes in particular had in mind a relatively loose confederation.

The Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians all spoke the same language (Serbo-Croatian), but the Serbs used the Cyrillic alphabet while the others used the Latin alphabet.

The Slovenes, Macedonians, and the Albanian minority in Serbia and Montenegro had their own languages.

The Serbs, Montenegrins, and Macedonians were Eastern Orthodox Christians. The Croats and Slovenes were Roman Catholic. The Bosniaks and the large Albanian minority were Muslim.

The populations were all mixed in together, with Serbs living in Croatia and Bosnia, Croats living in Serbia and Bosnia, and Albanians living in Serbia and Macedonia.

The country staggered on, an unhappy conglomeration with conflicting aspirations and identities, until Germany crushed it in 1941 prior to invading the Soviet Union.

After the war, the corpse of the country was unnaturally held together by communism.

With the collapse of communism in the 1990s, the country finally broke into its constituent pieces, although not without great bloodshed and destruction.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers