World Stamps

How stamps helped fund a Swedish explorer’s Central Asia expedition

By Christer Brunstrom

At a local charity shop run by Amnesty International, I recently picked up a book by Sven Hedin.

Titled Along the Silk Road, the book tells about Hedin’s 1933-35 expedition to Sinkiang (today spelled Xinjiang) in the northwestern part of China.

The purpose of the expedition was to explore the possibilities of building car roads through the Gobi Desert, where camel caravans were still very common in the 1930s.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Hedin’s expedition was financed by the Chinese government, which at the time was based in Nanking. This was a most difficult time in China’s modern history. The Japanese had turned Manchuria into a puppet state in 1932 and also were trying to expand their influence in other parts of China. Civil war was going on in different parts of the Middle Kingdom, with Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist forces on one side and the Communist revolutionaries on the other.

In distant Sinkiang, civil war was raging, with the Soviet Union playing an important part. Even in normal times it was a highly unsecure area, with groups of robbers attacking caravans and other travelers in the province.

At the same time, many evangelical churches in Sweden had established mission stations in numerous isolated parts of China, including Inner Mongolia and Sinkiang. The missionaries frequently were running hospitals and schools serving the local populations.

Sven Anders Hedin (1865-1952) was born in Stockholm and became not only a geographer but a topographer, explorer, travel writer, and photographer. He first came to Central Asia in the 1890s, after having obtained a doctorate in geography at the University of Halle in Germany. He traveled in areas that until then had been white spots on our maps.

In 1896, he discovered not only Lop Nor, a salt lake that changed its course around the turn of that century and became known as the “Wandering Lake,” but also ancient cities that had been important along the trade routes between China and the rest of the world.

Back home in Sweden, Hedin wrote numerous books about his travels and went on tours to speak about his experiences. In 1902, he was raised to the untitled nobility by King Oskar II, becoming the last Swede to receive a charter of nobility.

Hedin was an excellent organizer, and in 1927 the German airline, Lufthansa, employed him to explore the possibilities of establishing air communications between Europe and the Far East.

The explorer was then involved in the Northwest Scientific Expedition, which lasted from 1927 until 1933. It included some 50 Swedish, German, and Chinese scientists and researchers. They made numerous important scientific discoveries in Inner Mongolia and Sinkiang. The expedition was financed not only by Sweden but also from international sources.

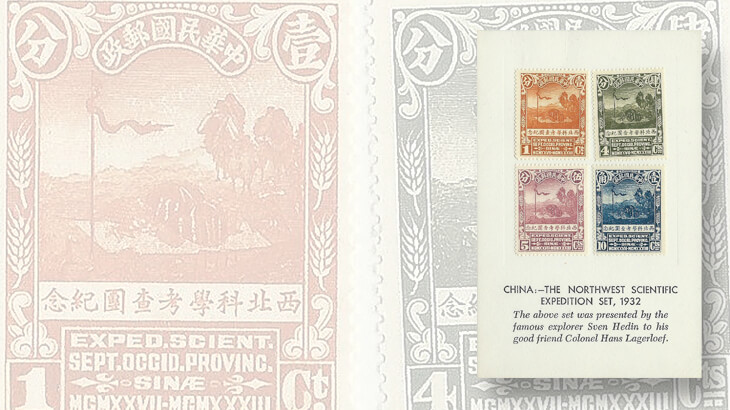

In 1932, China released a set of four rather exceptional stamps (Scott 307-310). The quartet, of four different denominations (1¢, 4¢, 5¢ and 10¢), was printed in a quantity of just 25,000 sets, which is tiny for a Chinese stamp issue.

The design features a painting called Nomads in the Desert, which (at least at the time) was part of the collections of the Palace Museum in Peking (now Beijing).

The stamps were issued in support of the Northwest Scientific Expedition, and the arrangement was rather peculiar to say the least: 4,500 sets were sold at some post offices in China, and the remaining 20,500 sets were handed over to Hedin to be sold to help finance his expedition to Sinkiang.

The set of four denominations had a total face value of just 20¢ and was sold at face value at the post offices, but was sold for $5 (Chinese dollars, or yuan) by Hedin.

At the time, lots of collectors purchased the stamps, and some wealthier persons acquired larger quantities.

Col. Hans Lagerloef, a Swedish-American philatelist of substantial means, apparently bought a large quantity of the issue. I believe Lagerlof’s holding was later acquired by Canadian dealer Kasimir Bileski, who marketed them for many years until sold out.

Illustrated with this column is a card with a set of the four stamps lightly hinged to it. The text on the card reads: “China: — The Northwest Scientific Expedition Set, 1932. The above set was presented by the famous explorer Sven Hedin to his good friend Colonel Hans Lagerloef.”

The card’s text is not totally correct, though the men probably were acquainted with one another. The colonel actually was supporting Hedin by buying a large quantity of the stamps.

In all probability, this card was prepared by Bileski, who in many ways was a marketing genius.

Today, the stocks that once existed have been dispersed, and the set is valued highly in catalogs ($116 mint or used in the 2017 Scott Classic Specialized Catalogue of Stamps and Covers 1940-1940). It has proved to be a pretty good investment for collectors who bought the sets for less than $20 many years ago.

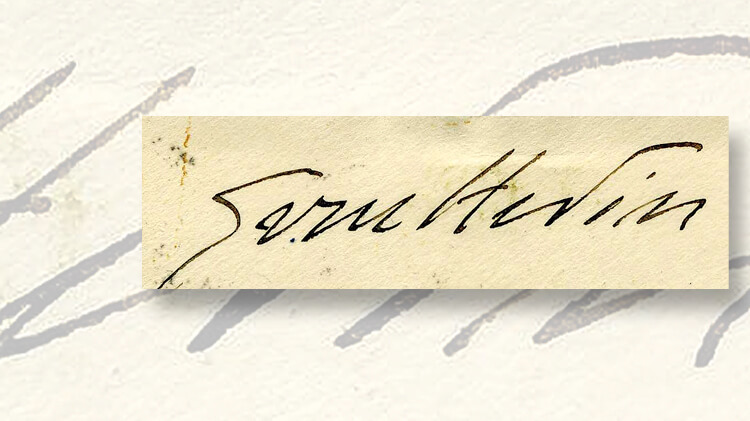

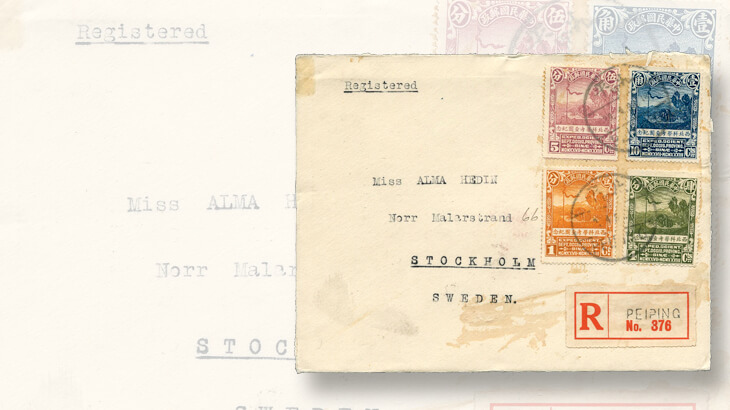

Sven Hedin was very busy mailing covers franked with the stamps to his sister, Alma Hedin, in Stockholm. The covers were then marketed to collectors. Some covers, including the one illustrated here, were signed by Hedin on the back, making them even more desirable.

At the time, finances were short for the Chinese government, and this rather unorthodox stamp issue was seen as a way of contributing to the success of the expedition.

During his travels, Hedin was continuously writing diaries that could then be transformed easily into book form. His descriptions of his travels are rather detailed, including frequent mentions of meeting fellow Swedes in the most unexpected places.

For several months in 1934, Hedin was held prisoner in Urumchi, Sinkiang’s capital. He had absolutely nothing good to say about this city or the people living there. He very much preferred the free life and even the hardships out in the deserts.

His dream was always to visit the holy city of Lhasa in Tibet, and on his third Central Asian expedition, in 1905-09, he came very close, reaching Shigatse in Western Tibet before being forced by local authorities to leave the country.

Before and during World War II, Hedin was a strong supporter of Hitler’s regime in Germany. He even met the German leader on one occasion. Hedin believed that Germany was the only country that could oppose Russian expansion in Asia and Europe.

Hedin’s support for Nazi Germany made him an outcast, and he had been stripped of some of his academic honors by the time he passed away in 1952.

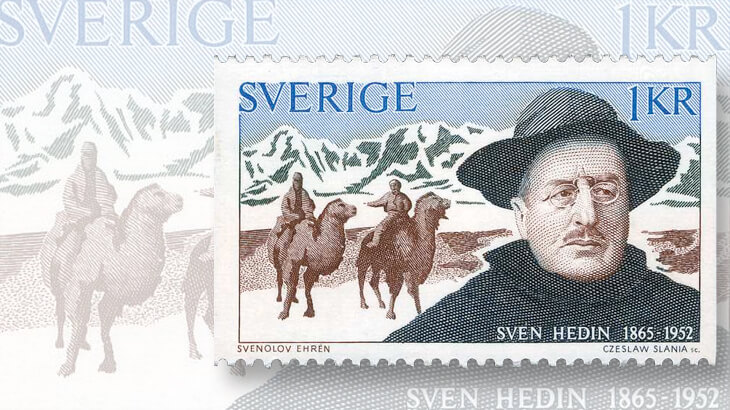

In 1973, Hedin was included in a set of five Swedish stamps remembering important explorers. The 1-krona stamp (Scott 1009) depicts Sven Hedin and, appropriately, camel drivers in a desert somewhere in Central Asia.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers