World Stamps

Why some airmail stamps are not listed as such in the Scott catalogs

By Marty Frankevicz

A few weeks ago, the Scott editors received a letter from a catalog user:

“Can someone enlighten me as to the logic or reasoning for not listing a stamp, which clearly states on it that it is an airmail stamp, but is not given an airmail designation of C in the Scott Catalog?

“I am referring to the Stamps of Egypt, where the C (airmail) designation is used in the catalog up until 12/13/2000 (Egypt Scott #241), this is the last stamp that is given the C designation identifying it as an airmail issue.

“BUT there are stamps issued by Egypt after this date which have indicated on the stamp that they are airmail, BUT they are listed with ‘regular’ Scott numbers and are listed along with the commemorative and definitives.

“It seems like the omission of identifying certain issues by giving them an airmail (C) designation started before 2000. Some examples are: Egypt Sc#1530; 1563; 1570; 1576; 1613; 1621; 1623; 1631; 1639 and the list goes on! In all cases the stamps have printed on them ‘airmail’ and most have notes in the Scott Catalog saying that this issue is airmail, so why was it not given an airmail (C) designation? Explain the logic please so that I may understand.

“I know in the case of U.S. issues there were no more stamps printed with ‘airmail’ on them when most mail went any distance by airmail anyway.”

Answering the writer’s question requires a bit of a history lesson about the Scott catalogs.

When the Scott catalog was in its infancy in the 1870s, the editor realized that there were stamps created for all sorts of different purposes, and separating these categories made sense.

Thus postage due stamps were listed separately from regular postage stamps, Official stamps, revenue stamps and any other category for which stamps were being created.

In the late 1880s, the catalog was still rather thin because there weren’t that many stamps, but the editors realized that assigning catalog numbers to each stamp listed would be helpful to facilitate the sale and organization of dealer stocks and collections and eliminate confusion.

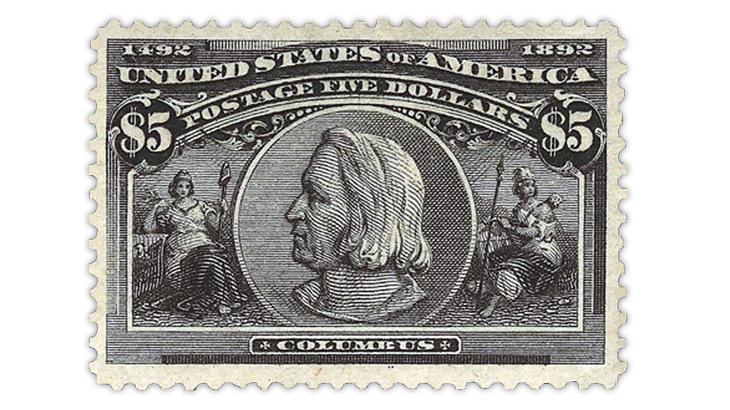

The initial Scott numbering system was solely numeric. For example, the 1895 catalog listed the United States $5 Columbian stamp, shown in Figure 1, as No. 202.

However, after a small gap of open (unassigned) numbers, the first carrier stamp was assigned No. 251 in the catalog, the first postage stamp No. 401, and the first Official stamp No. 450. It’s almost as if the editors did not realize that there were going to be a lot more stamps coming.

By the time the 1911 catalog was published, more stamps had been issued, and the books became thicker. More stamps had been added in the U.S. postage section so that the $5 Columbian was now Scott 245. The last stamp in the postage section was the 1909 2¢ Hudson-Fulton stamp (337).

Official stamps in the 1911 edition started with No. 501. Carrier stamps started with No. 801, and postage due stamps started with No. 1201. It is obvious that a whole lot of catalog number changes were still being made.

The Scott catalogs were typeset in those days, and someone had to change all of the catalog numbers in the various back-of-the-book sections. The late 1910s was the infancy of mail transport by air, and countries were creating special stamps for franking letters sent by airmail.

The U.S. airmail stamps now listed as Scott C1-C3 were originally in the postage section as Nos. 430-432, but in the 1930 catalog they were placed in a separate airmail section as Nos. 1300-1302.

So even then there was a fair amount of renumbering being done in the catalog. It wasn’t until the 1940 catalogs that Scott’s alpha-numeric system was created.

Aerophilately became very popular in the 1930s and 1940s, so much so that the Sanabria catalog handled just airmail stamps, and Scott came out with its own catalog focusing on them as well.

The stamps generally had face values higher than regular postage, there were a fair number of rather scarce and expensive stamps, and the number of stamps to collect for most countries wasn’t excessive.

For some foreign catalogs, airmail stamps were not quite as big a deal, and in those catalogs, airmail stamps and semipostal stamps are listed together with regular postage stamps.

While it makes sense to separate postage due stamps and Official stamps from regular postage stamps in catalogs because of the differences in the ways those stamps are used, separating airmail and semipostals from regular postage issues is a bit more artificial.

If you take a look at the arrangement of the Scott catalog today, you will note that up until 1920, there are not that many stamps that were issued that collectors would call commemorative stamps. Most commemoratives were issued as single stamps, and not an awful lot of commemorative sets were created.

However, in the 1920s and 1930s, countries were starting to issue more commemorative sets. Until then there had not been too many sets, if any, in the catalog that had stamps in multiple sections.

The 1932 Garibaldi set of 17 from Italy was issued with 10 regular postage stamps, five airmail stamps and two airmail special delivery stamps in it (Scott 280-289, C35-C39 and CE1-CE2). The editors dutifully separated the airmail and airmail special delivery stamps from the regular postage stamps.

A 75-centesimo Garibaldi postage stamp (Scott 285) is pictured in Figure 2.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a number of Latin American countries began issuing numerous airmail stamps, but they were also issuing many of these airmail stamps as part of a set with regular postage stamps. The editors continued to separate the airmail stamps from the postage stamps in the catalog. However, that became problematic for dealers.

The dealers had no real need to separate the airmail stamps from the regular postage stamps because they were selling the sets intact, not as individual stamps.

Dealers would place ads in Linn’s showing their price lists, which gave prices for a sequence of postage stamps in a set, followed by prices for the airmail stamps in that set, followed by a similar sequence for the next set of postage and airmail stamps, and so on.

This became a challenge for dealers when typing out their price lists and a typesetting challenge for the newspapers that printed the price lists.

It also became a nightmare for the Scott editors when they had to calculate set totals across catalog sections in a time before computers.

Also flipping back and forth from the regular postage section to the air post (airmail) section to try to identify a stamp wasn’t much fun for collectors either.

By the end of the 1970s, however, most countries produced many fewer stamps with airmail designations on them. By that time, airlines were carrying more and more mail, so a premium price for airmail service was seldom being charged for domestic mail service. The premium was kept for international service.

Though countries were still producing stamps for airmail rates, those stamps could be used for paying any postage fees. Collecting airmails waned as a popular area of philately because airmail transport became the norm rather than the exception.

In the 1980s Scott began computerizing its catalogs. The catalog editor, who dealt with all of the complaints from Latin American dealers and had the onerous task of checking the cross-section set totals (which was farmed out to the Scott accounting staff), realized that fewer and fewer cross-section sets were being created.

He thought it was perhaps best, from that point on, to keep all of the stamps in a set together. He decided not to renumber all of the previously issued cross-section sets that were scattered all over the catalogs.

Renumbering all of those cross-section sets would have been a nightmare for the editors, and it would have forced dealers to renumber their stock, which they do not like to do.

Scott renumbered just the postage section in Belgium in the mid-1980s and received all sorts of complaints from dealers and collectors alike. As much as the catalog editors of the early 1900s had no problem with renumbering items, today the Scott editors try to avoid it as much as possible.

So that’s where the Scott catalogs are today. If there’s a new set containing regular postage stamps and airmail stamps, the set is listed in the regular postage section with a footnote pointing out which stamps are the airmail issues. If an airmail stamp is issued by itself, it is listed in the air post section.

The Scott catalogs have changed significantly over time as stamp collecting has changed and the way stamps are issued has changed.

The Scott editors endeavor to produce catalogs that are essentially the language of our hobby. It is important for each stamp to have a unique identification number, and it is important to try to make it easy for collectors and dealers to identify their stamps.

This is no easy task when the six A-B volumes of the 2020 Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue combined have about 11,000 pages and thousands of illustrations.

Having listings for stamps issued in the 2020s be consistent with listing styles for stamps issued in the 1880s or 1950s is less important because the Scott editors know that what was important decades ago is not necessarily going to be something of importance today.

For most countries today, Scott lists values for entire sets of stamps rather than values for the individual stamps that comprise the set because dealers are selling sets rather than individual stamps.

If Scott were to list every stamp individually, the catalogs would be far bigger.

The Scott editors try to be fluid in how they handle situations as stamp collecting evolves into something that the hobby’s forefathers undoubtedly never would have envisioned in the 1880s.

Marty Frankevicz is the Scott New Issues editor.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers