World Stamps

A new discovery made among the cantonal stamps of Zurich

Unveiling Classic Stamps — By Sergio Sismondo

During the centuries when Europe was dominated by the Holy Roman Empire, the region now comprising Switzerland was part of the empire but was considered to be a land without political unity. Gradually, however, the people of one valley and then another formed local governments that became known as cantons.

From 1351, Zurich was a member of the confederation of independent cantons, with sovereign and autonomous governments. In fact, in 1351 Zurich was named the capital city of the confederation.

Being the capital involved few centralized functions, because each canton was fiercely protective of its powers and institutions. The union was bound together mostly by historical and cultural commonalities.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

It was a fact of life, like snowfall and the occasional avalanche, that foreign powers attacked Swiss frontiers in relentless pursuit of annexation. Austrians were at it more than others, but French and Germans occasionally participated as well.

William Tell (Philately of Switzerland, Linn’s March 13 issue), an able warrior and leader, became the principal symbol of Swiss defense against imperialist aggressors. All the able-bodied population, bar no one, acquired the skills and weapons to fight incursions. All, in one way or another, followed the example of William Tell.

This characteristic of Switzerland, which some might find to be anachronistic, is still very much alive today and in large part accounts for Switzerland’s continuous independence despite two world wars and other regional conflagrations that redrew the maps for many other countries.

The last time Switzerland was seriously disrupted by a foreign power was in 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte subjugated Switzerland to his will, in a moment of misguided euphoria, and created the Helvetic Republic, governed by a centralized government under the command of his appointed puppet ruler with the fancy title of “Le Landammann de la Suisse.” But the centralized new republic did not last long — only about five years. Between 1803 and 1815, many Swiss institutions devolved their activities and legitimate authority to the cantons.

A Tiny Bit of Postal History

Written communications between cantons were of fundamental importance for business. Their passage was complicated. All letters were posted unpaid, with all charges to be paid by the addressee. It is said that it was better that way, because prepaying postage could be interpreted as a put down, suggesting the addressee was too impoverished to afford the postage due.

Cantons had different currencies and different tariffs, which meant that a letter crossing several cantons received a number of rate markings, which to the modern collector are practically indecipherable. Consider the astonishing fact, for instance, that before 1848 in Switzerland, there were 19 different currencies in circulation.

Nonetheless, and in spite of such fragmentation, the confederation sailed through the centuries with few troubles other than the frequent requirement to call up an army to defend one or another frontier.

At the time of Napoleon’s Helvetic Republic, the diverse postal systems of each canton disappeared, to be replaced by a central postal authority. But, along with other institutions, quickly after the return of normality in 1803, the centralized post office gave way to a return of postal institutions governed by the cantons. A more thorough example of devolution is hard to find in European history.

The Advent of Zurich Stamps

Having studied the positive experiences reported by the British postal administration after the introduction of stamps for the prepayment of postage, and the rate reductions that accompanied, the administrator of posts of Zurich submitted a report to his cantonal government detailing the advantages gained by the British.

The report suggested Canton Zurich should implement the same method of prepayment with adhesive postage stamps and similar uniform reduction of rates that went along with the reform. This report was dated August 1842.

The report suggested new rates of postage: 4 rappen for city mail, and 6r for cantonal mail, for single-weight letters. The thought was also advanced that this simplification would greatly reduce the work burden of postal clerks, thus rendering the entire system more efficient.

Deliberations were not prolonged, and the Zurich State Council decided, during its meeting of Jan. 21, 1843, to introduce postage stamps and reduced tariffs in their territory for prepayment of postage in the same manner as the British.

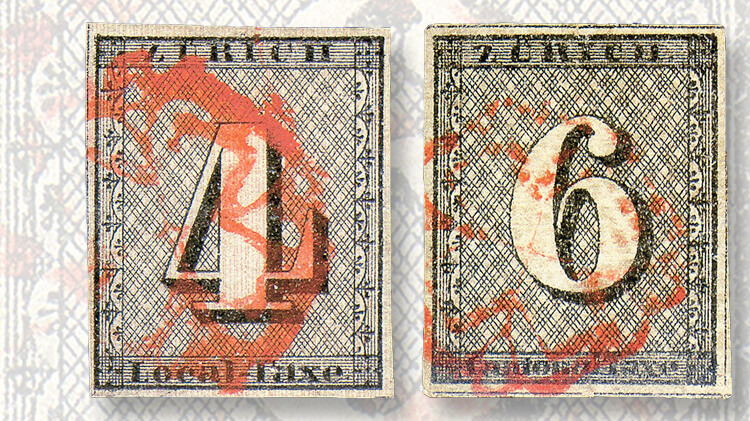

A few weeks later, on March 1, 1843, with characteristic Swiss efficiency, stamps denominated 4r and 6r were produced by lithography in the printing shop of Orell, Füssli & Company, of Zurich. A decree enshrined the new rates exactly as suggested by the administrator five months before: franking for a local letter was decreed to be 4r, and for letters traveling beyond city limits, anywhere in the canton, the postage required was 6r. For local mail, 30,000 stamps were printed, and about 165,000 stamps were produced for cantonal mail.

The stamps were black and rectangular and of about the same size as those of Great Britain. But the similarities end there. There was no queen or king to glorify.

The main feature in the design is the numeral: “4” or “6.” Above, in the frame provided, is written ZURICH. Below, also in the frame, is stated the purpose of the adhesive: “Local-Taxe” for the lower denomination and “Cantonal Taxe” for the higher denomination. On the sides are inconspicuous ornaments.

In the background is a tightly woven crisscross pattern of thin lines. The strong shadows given to the numerals create the effect of three-dimensionality, almost as if the numbers were floating above the background texture. The design is elegant for its simplicity and lack of pretension.

The Printing

The stamps were manually etched five times, and a transfer plate was made showing the five types, naturally showing minor differences between each image. The strip of five stamps was then transferred 20 times onto the lithographic printing stone, yielding, therefore, sheets of 100 stamps.

Minor flaws appeared in the stone, and several retouches were made for correction and improvement. The printing was made on white paper with fine red lines running across it in a determined pattern. These lines can be vertical or horizontal, depending in which direction the paper was introduced in the lithographic press. A brownish gum was applied to the sheets before the stamps were sent to post offices.

A huge variety of forgeries exist, from very obvious to extremely dangerous. If the reader has examples thought to be genuine, it is best to submit them for expertization.

The Cancellations

The stamps were distributed to post offices beginning in early March 1843. They were canceled with different devices. The more common cancellations are the red “rosettes,” as shown nearby. The same rosette struck in black also is commonly found.

Needless to say the red postmarks are more attractive on the black background. Less common are the “P.P.” cancellations, of which there are several types. All other cancellations, including circular town-dated postmarks are very scarce to very rare.

Reprints

The French Legation in Zurich, in 1862, requested a second printing of the two stamps for archival purposes. This was executed with great care, with the difference that plain white paper was used, without the red background lines. Stamps from this second printing are available in the philatelic market, and are themselves rather rare and valuable.

The idea of reprinting stamps for archives and museums had become widely accepted in Europe by 1862. For example, Sir Rowland Hill requested complete sheets of all French stamps for the British archives, and did receive newly printed stamps in magnificent sheets, as requested.

The Rarest Stamp of Zurich

The timing of this article could not have been more propitious. A most extraordinary find took place in the past few months that has not yet been discussed in the philatelic press or literature. Let’s begin with the background facts.

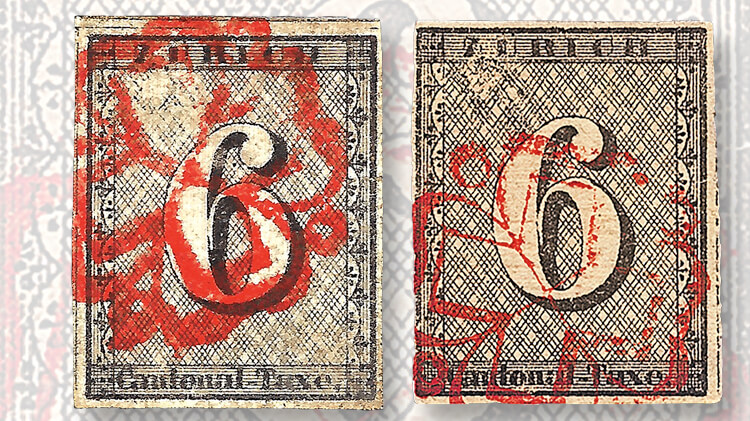

In the plate of 100 subjects of the 6r of Zurich, in position 98, is invariably found a retouch of the background at northwest, just under the ZU of ZURICH. From the shape and texture of the repair, it is easy to deduce that the repair was intended to fill in a “gap” or “tear” that had occurred in the background design. This flaw was not present in the proofs. Therefore, it happened during the production run of the stamps. However, a mystery arose: no stamps could be found showing the flaw before being repaired.

The stamps have been around for 174 years, and 1,650 examples of position 98 were printed. It would be normal to assume that examples with the retouch would be found, and also it would be normal that examples showing the fault before being repaired could also be found. That is the case in many other classic stamps that have been retouched and repaired: we find repaired impressions, and also find stamps showing the flaw or break before the repair.

Examples of these cases, which permit collectors to match before and after repair couplets, occur in various early stamps of Great Britain and Canada, and most famously in the 1859 stamps of Sicily, to mention just a few.

But in the case of Zurich’s 6r position 98, examples without repair could not be found — they lay well-hidden. Their absence led many to believe that the fault occurred before the printing of the stamps commenced. But that was not to be the case.

Recently, thanks to the careful research of Gottfried Honegger, of Schmerikon, Switzerland, one example finally surfaced, putting to rest the erroneous hypothesis. It is a four-margined stamp, canceled with a neat red rosette postmark. Within one of the loops of the cancellation it shows, as plainly as can be imagined, the gap in the background that was the reason for the repair.

This is the only example recorded of position 98 before the repair, and is therefore unique at this point in time. Perhaps others will surface, although that event is statistically most unlikely to occur.

Shown nearby are the before and after examples of position 98.

The image of the position 98 example without repair is courtesy of Gottfried Honneger of Schmerikon, Switzerland. All other images are from the archive of Sergio and Liane Sismondo.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers