US Stamps

The possible problems lurking in your stamp collection

U.S. Stamp Notes — By John M. Hotchner

In commenting on previous columns in this ongoing series on expertizing, a couple of Linn’s readers have suggested that it is not only current purchases of classic material that need to be expertized: You might have stamps and covers purchased much earlier in your philatelic career that should be authenticated.

This rings a bell with me because I have some items in this category, and I’ll bet many other collectors do as well.

Why bother with expertizing? Here are three reasons.

1. It is always good to verify that the stamp you bought as a certain Scott number actually is just that.

2. Much as we might like to avoid the issue, we all eventually either disperse our collection, or leave it to family to disperse. In either case, having certificates on the items that are most likely to bring significant returns facilitates the process.

3. While expertizing might not be cheap now, the cost will only increase into the future.

With regard to the second and third reasons, allow me to share a story. Not long ago, I was contacted by the family of a friend who had passed away 10 years earlier.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

His collection of United States color-omitted stamps had resided in a safe-deposit box all that time. The family agreed that now was the time to break up the collection and sell off the material. Would I help? they asked.

Of course, I was happy to do that. The collector was a discriminating buyer, and he had amassed a very nice collection. However, not a single one of his acquisitions had come with a certificate, and he was expert enough to make his own judgments.

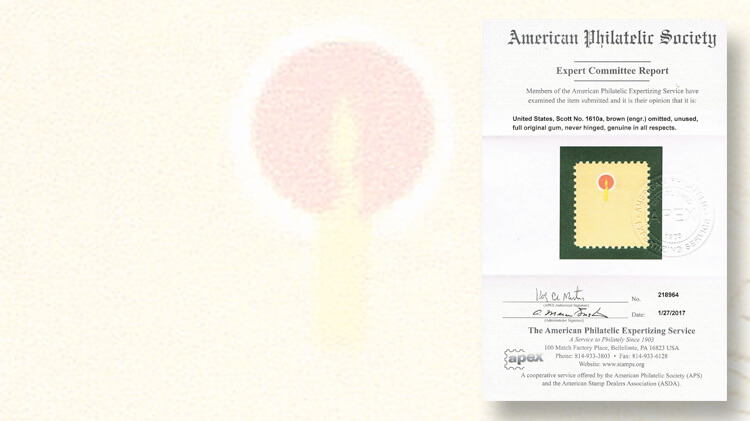

The problem is that he was a quiet collector. You could not say that a given error had come from his collection and have its bona fides immediately accepted. So, in order to obtain the best prices for the items in his collection, I first had to get certificates for them. An example for Scott 1610a, the $1 Americana Candleholder with engraved brown omitted, is shown.

Not having certificates delayed the process of placing the material with an auction firm by three to six months, and cut into the family’s realization by the up-front cost of a couple of thousand dollars.

Had he gotten certificates at the time he purchased the stamps, he would have paid much less for expertizing, and the error stamps would have been immediately salable.

Why, you might ask, not just sell stamps or covers “as is” and let the buyer worry about getting certificates? That is certainly an option, and you or your estate are only responsible for the cost if the certificates come back bad. But you will still wait to get your money because the auction firm will not pay out until all questions of genuineness have been settled.

There are two other things to consider, too. First, while some buyers will bid on an item that does not have a certificate, others will not. This limits the competition.

Second, some buyers — most, I would say — will bid higher on lots that they know to be good based on a certificate. In this way, your cost to obtain the certificate tends to be repaid buy the successful buyer.

While we are talking here about color-omitted errors, there are other U.S. stamps that are equally problematic without certificates. These include early high-value coils, high-value 19th-century U.S. stamps on cover, early U.S. mint stamps, rotary coil waste released in sheet form, U.S. possessions overprints, and any U.S. stamp where the used catalog value is higher than the mint catalog value.

In many of these instances, the stamp might be genuine, but it might also be altered or repaired to improve its appearance. Here again, the acquisition of a certificate now saying that the stamp (or cover) is accurately described with no faults makes it much more readily salable when the time comes.

Actually, I have misspoken. Certificates don’t usually say “with no faults,” rather, they will list faults if any are present; the absence of any faults noted is what a buyer is looking for.

There is another circumstance in which a certificate is needed for a stamp or cover you already own. If you are an exhibitor, as I am, you will find that when doing the creative work of nursing a new concept into a showable exhibit, you may well take stamps out of your album to use in your exhibit.

When you do this, you will want to be absolutely certain that what you are showing is the genuine article. It is frowned upon, and properly so, to show a misdescribed or altered stamp or cover. It reflects badly on your philatelic knowledge. For me, getting a certificate on anything I know might be questioned in an exhibit is essential.

Possessions Overprints

I mentioned U.S. possessions overprints earlier in this column. These are stamps of the United States from the late 1890s to early years of the 1902-03 series that were overprinted for use in Cuba, Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. There are many other overprints in the possessions realm, both on later U.S. stamps and on stamps produced with the name of the possession included as part of the basic design.

It is the earlier overprints that I want to focus on here. There are dangerous fakes, and there are some so amateurish that one wonders why the perpetrator bothered.

In the nearby illustration, the first 4¢ Lincoln stamp has a genuine Philippines overprint. It is followed by two almost credible fakes. Note that these overprints are in a slightly different typeface and are smaller.

Also pictured are an 8¢ Martha Washington with a really bad Philippines overprint, and two 2¢ Washingtons with poor Cuba and Puerto Rico (“Porto Rico”) overprints. None of these fakes would fool a specialist.

The fact that they are on low-value stamps indicates that the intended market was not specialists, but rather the album collector who was intent on filling spaces.

The price difference between the basic used stamp and the overprinted version made the effort worthwhile. The point here is that on stamps with higher catalog values more care would have been taken — at least in some cases — so a certificate is needed to be certain of authenticity.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers