US Stamps

Two varieties that have confused collectors for nearly 50 years

By John M. Hotchner

There are two types of varieties that are more than 45 years old that cause confusion among collectors who like to catch printing flaws: joint lines where they are not expected and plate numbers or design elements with a ghost impression.

Collectors often ask about these items and sometimes even submit them for expertizing, wondering or hoping that they might be rare errors. I am using this month’s column to set the record straight.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

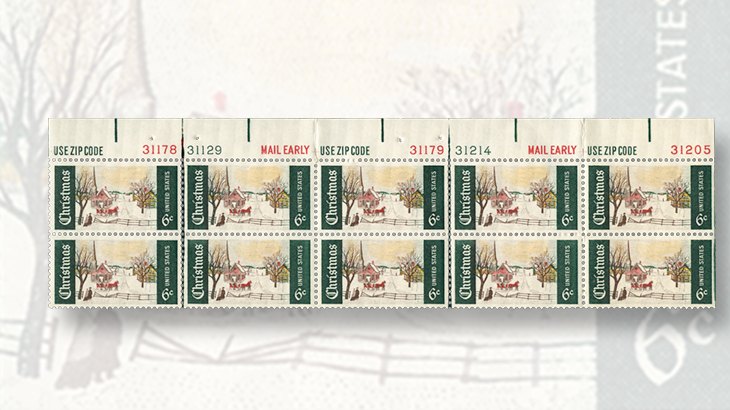

For an example of joint lines where they are not expected, look at the plate strip of 10 1969 6¢ Winter Sunday in Norway, Maine, Christmas stamps (Scott 1384) shown nearby. Notice that there are vertical green and red lines between rows two and three, and three and five.

If a collector had found such a strip and wanted an expert’s opinion, the finder would write something like, “These must be rare since I can’t find joint lines for this issue listed in the Scott catalog.”

This is not an irrational conclusion, and the phenomenon is seen even more often on contemporary coils that — like the 1969 Christmas stamps — were produced on the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s Huck press. Some of those coils are shown nearby.

Coils from 1908 onward existed either in the form of Scott-listed guideline pairs or joint-line pairs, that is until the Huck press was used to produce U.S. stamps beginning in 1969. As new stamp catalogs were published, collectors noted that joint-line pairs were not listed for Huck press products, even though they clearly exist.

Why not? The answer lies in the fact that they are not consistent, as are the line pairs from other presses. Huck press line pairs range from being hardly visible to being quite heavy. They also are seen in various inconsistent combinations of the colors used to print the stamps.

In fact, Huck line pairs were not planned, as were the joint-line pairs from other presses. Line pairs from the pre- and post-Huck eras were the result of coils being produced on rotary presses that had two semicircular plates wrapped around the printing cylinder. The plates did not fit perfectly where they met. The depression between the plates filed with ink and printed a line on the roll of printing paper with predictable regularity, usually every 26 stamps.

Because the lines were between two stamps and they were expected to be there, joint-line pairs became a collectible variety and are listed by Scott.

The joint lines also were a feature of sheet stamps, but in that case, the lines were printed in the margins, away from the stamps, so they were not considered to be collectible nor were they given listings in the catalog.

The Huck press was quite different. Instead of semicircular plates, it used curved plates that were the width of four definitive-size stamps, or in the case of the 1968 and 1969 Christmas stamps, the width of two commemorative-size stamps.

Sometimes those plates fit so well together that there was no printed line where they met. At other times where there was a small gap between the plates, the ink entered those gaps when the plate was inked, and a line showed up between printed stamps, no matter whether they were coil stamps or sheet stamps.

Because the lines were not intended and were so variable when they did occur, the Scott editors decided not to list them. But just because a listing does not appear in the Scott catalog does not mean that the items are scarce or expensive. In fact, most Huck joint-line varieties are neither, but they are interesting and collectible.

Another confusing aspect of Huck printing applies only to sheet stamps: Why are there no side margins on issued sheets, only the top and bottom margins?

The Huck press plates produced a continuous roll of stamps called a web with plate numbers and other marginal markings at either edge of the web, but the stamp images were continuous on the web — both across the web and in the direction of travel through the press. In other words, there were none of the interior margins we are used to seeing with stamps printed by non-Huck presses.

What that means is once the web was sectioned into post office panes of 100 definitives or 50 Christmas stamps, there was no margin on three sides.

A slight miscut might show a piece of the adjoining pane, and rarely an 11th definitive stamp. With a pre- or post–Huck stamp, such a miscut would only result in a margin that might be a little larger or smaller than normal, and no one would pay any attention.

Doubled Plate numbers

A second often-seen confusing effect is called a “ghost impression.” The name comes from the light second impressions that may be left after the tagging process.

It is most often seen in plate numbers, but can also be found in design elements. A good example of the doubled plate number effect can be seen on the 1971 8¢ 450th anniversary of San Juan, Puerto Rico, commemorative (Scott 1437).

The directly printed plate number is 33201. Slightly displaced to the lower left is the ghost plate number 33202. Both numbers (and others, too) were used in the printing of this issue.

Where did the ghosted 33202 on the plate block come from? Most of the picture on the stamp was printed by offset lithography. After that, some of the highlighting in the design (in red brown and dark brown) and the lettering including the plate number (in black) were added by engraving. Once that was done, the printed sheets were put through another station to add the taggant.

Now, picture the wet sheets coming out of the intaglio printing station, and going through a roller that applies the tagging material.

Intaglio ink is notoriously thick and slow to dry. A station equivalent to a small oven tries to speed that process along before the tagging operation. But if the ink has not completely dried, and most often this seems to happen to the outside of the sheet, the tagging roller can pick up some part of the design and/or the marginal markings as the sheet goes through.

That wet ink does not stay on the tagging roller. Rather, it will then offset onto the next sheet to make contact with the roller surface.

If the alignment is perfect or close, there will be little to no effect on the design part of the stamp. But if the alignment is off even a little bit and the plate number of a preceding sheet is different from a succeeding one, the plate number of the preceding sheet will show up as a ghost impression on the succeeding sheet.

A nice example of ghosting can be seen in the design of the 1973 8¢ Rural America Angus and Longhorn Cattle stamp. Here it is the blue “Rural America” that is affected, and it is doubled downward.

I have seen such ghosted items submitted for expertizing as double printings, which means that the design was somehow printed twice on press. As I have already explained, they are no such thing.

These ghosts have been found on virtually all tagged issues that include intaglio elements from the introduction of tagging with the 5¢ first-class-rate era until the Bureau of Engraving and Printing seems to have found a way to eliminate the problem sometime in the 1980s.

They are neither rare nor valuable. In fact, they are common enough to be found in your favorite dealer’s plate-block stock, often at the same price as the normal block, or at a dollar or two more. It is also possible to find a third ghosted number, though that occurs less often.

What does have significant additional value is a tagging ghost where a large part of the design also is doubled, but it is still classed as a variety, not an error.

These varieties make an interesting addition to your album, but get no catalog listing and have only minimal additional value.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers