US Stamps

10 modern-era examples of when expertizing is not needed

By John M. Hotchner

In the U.S. Stamp Notes column on expertizing published online July 27, I discussed 10 instances from the first hundred years of United States philately in which expertizing is not essential to a finding that the stamp in question is or is not a genuinely scarce item.

This time, I am presenting 10 items from the past 70 years.

Situation 1

In the 1950s, multicolor printing became more prevalent in the production of U.S. stamps. Prior to that, the use of two or more colors on a U.S. stamp was a rarity: Multicolor printing was expensive, time consuming, and reserved for special issuances only.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Curiously, the problem most often seen with early multicolor stamps is color misregistrations, with color inverts in second place.

It was not until the 1960s that a majority of U.S. stamps were produced in multicolor and that missing colors became a serious problem.

In the 1950s and 1960s, multicolor designs were printed on the Giori three-color plate press, and later multiprocess presses that included both offset and gravure printing stations came on line. These presses represented significant advances in printing, combining both speed and complexity. This opened a window for new inking problems.

Suddenly, there were instances where individual printing stations ran out of ink, corner folds put part of a sheet beyond the reach of an inked plate, and misperforating of finished sheets could leave a design image that cut off a color.

Missing-color errors that resulted do need certificates. But it is important to remember that the presence of any part of the missing color disqualifies the stamp from being called a true missing color. The catalog description most often used is “color omitted,” and that means the entire color must be gone.

In other words, the presence of a single dot of color or shadow identifiable as the intended color disqualifies the stamp. If you have a 20x to 30x magnifier, look carefully at the area where the missing color is supposed to be. That is what an expertizer will do. If you see any vestige of a color, don’t bother sending in the stamp; it will not get a good certificate.

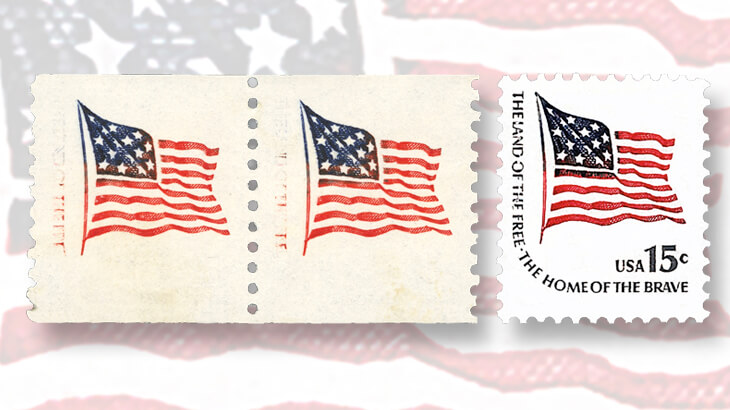

As an example, a coil pair of 1978 15¢ Americana stamps (Scott 1618C) is shown nearby. The stamp was printed in gray, dark blue and red. While part of the gray is missing, a shadow of it can be seen on the left side of each stamp.

Situation 2

A second category is what many think may be a missing color because there is a significant difference in colors between two stamps. In this case, there is no color missing, rather the stamps were printed using a process that relied on dots of five basic colors that are overlaid on top of one another to produce the colors needed for the design.

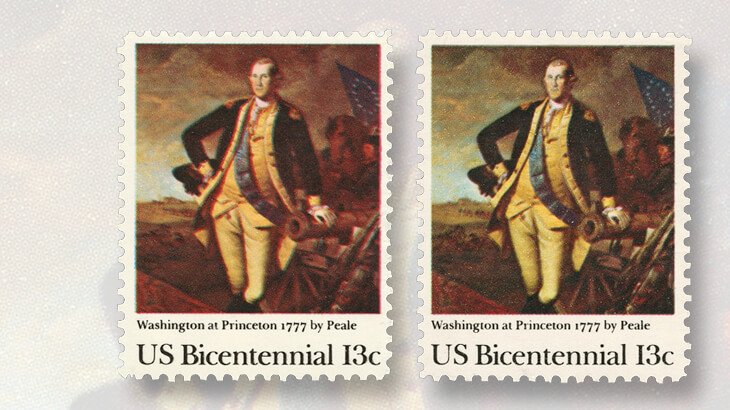

Our example is the 13¢ Washington at Princeton pair from the issue of 1977 (Scott 1704). On the left-hand stamp, the yellow of his uniform is bright, while on the right it looks like the yellow is missing.

This process relies upon the printed dots of color being of a certain size and intensity. If too light or too dark, the final product can be quite different from what was intended, and someone looking at the two stamps side-by-side can be forgiven for thinking that something is missing from one of the stamps. In the Washington at Princeton example, the red dots that give the yellow its brightness are weak on the stamp on the right.

Here again, because the naked eye will fool you, you need to look at the two stamps under high magnification, preferably 30x. This will tell you if there is a color missing, or if there is just a light print of one color that leaves a final color that differs from what was intended. Don’t bother sending in the latter; it may be a collectible variety, but not an error.

Situation 3

A third color category involves instances where one or more colors have been altered. This can happen on purpose; in other words, someone has used chemicals trying to create an error where one does not exist. Colors also can be altered by accident through exposure to chemicals in washing or intense light. Reds, yellows and oranges are most subject to being changed.

So even if you look carefully and all of a given color is missing, you also need to look at the white part of the stamp. If it appears flat or discolored compared to a genuine normal example, there is no point in sending the stamp in for expertization.

Another good idea is to check missing colors against a normal example using ultraviolet light. Often, the process of altering a color also will alter the tagging.

Situation 4

Let’s now turn to perforations — or lack thereof — on the next example of when expertizing is not needed.

When you have what looks to be an imperforate single, keep in mind that it is rare that you can get a certificate on a single. The protocol for collecting imperfs is that they must be in pairs.

The reason is that the placement of perforations is not always an exact science, especially when you are dealing with stamps produced in booklet form, with one or more straight edges. In the three examples shown, it is not hard to see how imperf singles can be created using a pair of scissors.

Situation 5

The next example is represented by the imperf pair of 1991 29¢ Desert Shield/Desert Storm stamps (Scott 2552) shown nearby. Even if you have such a pair, you might still not be home free. Always check your Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers and read any notes after the issue you have. In this case, the catalog states that horizontally imperforate vertical pairs are from printer’s waste.

Printers’ waste does not have the same status as errors. Basically, it is unfinished material intended to be destroyed that has made its way out the back door of security printers. It will not be listed as respectable errors, nor will it command error prices.

Situation 6

The sixth nonerror is often found on the 1968 6¢ Flag and White House stamp. Like color error candidates that are disqualified because of a single dot of color, imperf and imperf-between stamps are disqualified by the presence of even a single impression of a perforation hole. The 6¢ Flag is often seen with imperf margins, but virtually every example I have examined has the impression of the pins just inside the design. These impressions are visible only from the gum side of the stamp.

Situation 7

I am calling the seventh category “almost imperf.” Although I once saw an auction lot described like that, there is no such thing as “almost imperf.” It is or it isn’t. If one perforation hole or hole impression is present, it will not get a good certificate.

Situation 8

Doubled perforations are the eighth problem area. There have been dispensing machines that have left hole-like impressions. In addition, simple perforating machines can be used to produce second sets of holes.

Before submitting double perfs for certification, compare the second set of perforation holes to the ones you know are genuine. They must match exactly in gauge and in size.

Situation 9

Those same private perforators can be used to create modern rarities. The John Paul Jones 15¢ stamp (Scott 1789-1789B) exists in three perforation versions: perf 12 by12, 12 by 11, and 11 by 11. The 12 by 12 is a modern rarity, cataloging mint at $3,250. I have seen examples where the top and bottom gauge-11 perfs have been replaced by gauge-12 perfs.

The problem for the re-perforator trying to do this is that they must both match the genuine perf 12, and not shorten the stamp beyond what is credible. Both are difficult. So, before you buy or submit a John Paul Jones 12 by 12 for certification, you can rule out most fakes by comparing the candidate against a known genuine perf 11 by 12 stamp.

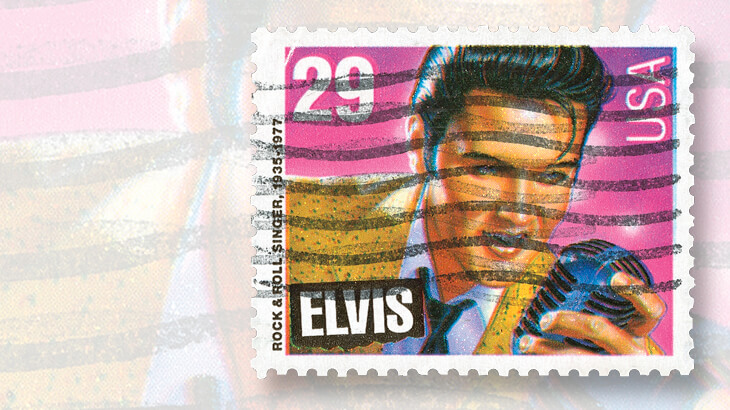

Situation 10

The 10th example is one of my favorites. The 1993 29¢ Elvis Presley commemorative stamps were very popular and often purchased by people who were not collectors. Half a dozen times since then, I have been asked if the slight color misregistration they have is a valuable double print error. It isn’t. A curiosity? Yes. Collectible? Yes. But not an error, and there is no need to have it expertized.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers