US Stamps

The scarce imperforate 4¢ Ulysses S. Grant stamp of 1908

Spotlight on Philately — By Ken Lawrence

The United States 4¢ brown Ulysses S. Grant stamp of the 1902 series (also called the Second Bureau issue) was issued without perforations in May 1908. Today, as Scott 314A, it is one of the scarcest and most interesting United States postage stamps of the 20th century, as well as one of the most expensive.

On May 12 the U.S. Post Office Department (POD) ordered the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) to ship a special order of 25 uncut 400-subject sheets of imperforate 4¢ Grant stamps to the Detroit, Mich., post office. The shipment departed Washington May 13 and arrived at Detroit May 15. The Schermack Mailing Machine Co., the authorized buyer, purchased all 10,000 stamps.

The entire batch was processed into coil rolls with the firm’s proprietary hyphen-shaped affixing-machine perforations, two vertical slots between each stamp, known to specialist collectors and listed by Scott as Schermack type III.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

No 4¢ Grant stamps survived in the original imperforate condition as issued, so the catalog listing is for stamps with Schermack private perforations, one of only two such stamps in the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue. (The other is Scott 482A, the 2¢ carmine-rose George Washington type Ia stamp of 1919.)

Other stamps with privately applied proprietary separations are listed in a separate back-of-the-book “Vending and Affixing Machine Perforations” chapter of the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers.

The Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries census of genuine Scott 314A stamps lists a total of 54 records, including multiples, 64 stamps in all. Of those, 21 are unused (nine singles, four plain pairs, two guideline pairs) and 43 are used (30 singles, one pair, and one strip of three off paper; two canceled on piece [one that includes the circular datestamp]; three singles on covers; and one strip of three on cover).

At least one additional used stamp has been reported but is not included in the Siegel census. In his 1943 book The Stamp Machines and Coiled Stamps, George P. Howard wrote, “One used copy with paste-up margin underneath has disclosed plate No. 4255.” Other writers have described a used Scott 314A with a guideline at the left. No stamp in the Siegel census fits that description either, but two show guidelines at the right.

The 2017 Scott US. Specialized catalog values a single example in unused condition at $100,000; in mint never-hinged condition at $230,000. An unused pair is valued at $250,000; an unused guideline pair at $375,000. A used single is valued at $52,500, a used strip of three at $300,000, and a used example on cover at $140,000. The amounts are in italics, indicating the listed items are traded infrequently and values are difficult to estimate accurately.

All but 50 of the 4¢ Grant imperforates were used on mass-advertising mailings prepared by the Winfield Printing Co., which used a Schermack high-speed mailing machine to affix the stamps and seal the envelopes. Approximately 6,000 envelopes contained circulars for Hamilton Carhartt Manufacturer, maker of overalls and other men’s work clothing, and about 4,000 for Burroughs Adding Machine Co.

Postage of 4¢ in 1908 could have prepaid a piece of third-class printed matter weighing from 6 ounces to 8 ounces, such as a catalog or price list, or fourth-class samples of merchandise weighing from 3 ounces to 4 ounces.

COLLECTORS TOOK NOTICE IN SEPTEMBER 1908

From October 1906 to March 1909 the POD provided sheets of imperforate stamps on special order to manufacturers and users of stamp vending and affixing machines. Those authorized buyers processed the imperforate sheet stamps into coils with private proprietary perforations. The most widely used affixing-machine perforation was Schermack type III.

Because the imperforate stamps were not placed on public sale, no published notices announced these issues. As a result, stamp collectors usually were unaware of their existence until previously unreported stamps were sighted on mail.

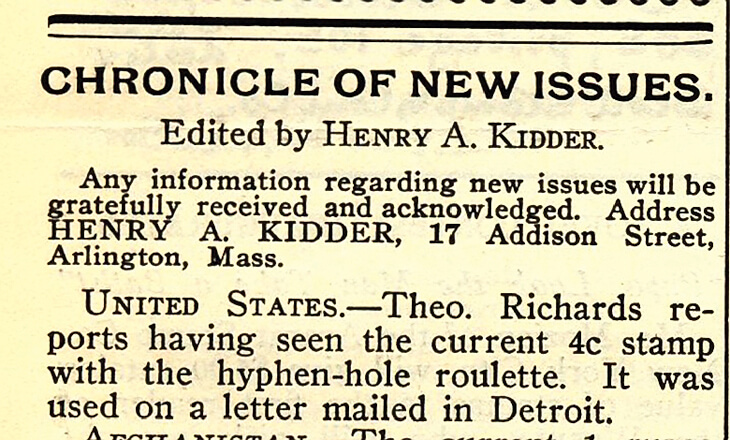

The Chronicle of New Issues column by Henry A. Kidder in the Sept. 5, 1908, issue of Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News reported: “UNITED STATES.—Theo. Richards reports having seen the current 4c stamp with the hyphen-hole roulette. It was used on a letter mailed in Detroit.”

That squib alerted specialists to the existence of the 4¢ Schermack coil stamps. They mounted a search for more, and attempted to identify the source in hopes of obtaining unused fully imperforate examples.

The Schermack Co. had sold quantities of earlier imperforate issues to stamp collectors and dealers, not only as finished coil stamps but also as unsevered blocks and as multiples that included marginal markings and selvage.

This time there were no remainders available to hobbyists.

Collectors and writers followed the paper trail to the Schermack office in Detroit as they had on earlier occasions, but by spring 1909 the firm was under new ownership and had changed its name to the Mail-om-eter Company, and was unable or unwilling to assist them in this quest.

At the time of the Mekeel’s report, the entire set of 1902 series stamps was in its twilight. It began to be replaced on Nov. 16, 1908. The new 1908 series pictured only busts of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. Scott 314A was superseded in 1909 by the imperforate brown 4¢ Washington stamp, Scott 346.

On March 13, 1909, imperforate sheets ceased being special-order stamps. Effective that date, any postmaster could order them for any customer. But all 1902 series stamps had been replaced by Scott 343-347 Washington and Franklin issues and by the carmine 2¢ Abraham Lincoln Centennial commemorative, Scott 368. No further reports of the imperforate 4¢ Grant appeared in stamp magazines until mid-1909, well into the Washington-Franklin era.

Collectors requested more information about the elusive imperforate stamps from Third Assistant Postmaster General Abraham L. Lawshe — not only about the 4¢ Grant issue but also about the scarce imperforate blue 5¢ Abraham Lincoln stamp, Scott 315, that had been issued a few weeks earlier to manufacturers of stamp vending machines.

In some respects the 5¢ imperforates seemed to be more difficult to collect than the 4¢ Schermack stamps because no imperforate or privately perforated 5¢ Lincoln stamps had been observed in the mail.

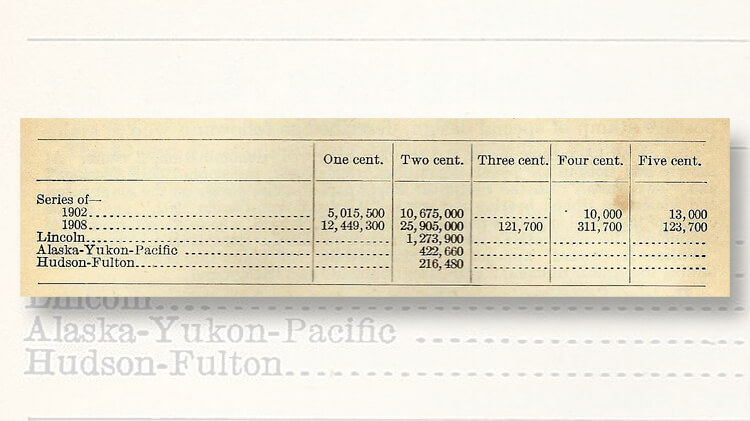

William C. Fitch, superintendent of the Division of Stamps, compiled from BEP invoices a report dated Jan. 14, 1909, “of unperforated postage stamps issued to date.” It showed that there had been only one issue of imperforate 4¢ Grant stamps, exactly 10,000 of them issued May 12, 1908. An original copy of the report signed by Fitch is in the Arthur M. Travers papers at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum.

The United States Philatelic Classics Society has made the Travers papers available online, which are searchable here. The two pages of this document can be viewed here and here.

In the April 1909 issue of Collectors’ Journal, Hugh M. Clark, who later edited the Scott catalog, wrote:

Of the values perforated for use in the [Schermack] machine, the general manager has told me that the company never perforated other than a one-cent or two-cent and possibly a 4c stamp, unless it was done without his knowledge and consent. The following therefore is a complete list of the varieties of the genuine Schermack perforation at the present date:

1c 1902. 2c 1902. 4c 1902. 1c 1908. 2c 1908. 2c Lincoln.

The remark “and possibly a 4c” started my question-mill at work. … I wrote to Washington concerning this and received a letter from which the following is an extract: “The 10,000 4c unperforated stamps, series 1902, were furnished the Postmaster, Detroit, Mich., in response to a call for stamps in that form to be used in a stamp-affixing machine.”

In the July 3, 1909, Mekeel’s, Kidder’s new-issues column reported correspondence obtained by Pennsylvania stamp scholar Lars Harald Kjellstedt, international secretary of the American Philatelic Society (APS), that verified “the 10,000 imperforate 4c stamps of 1902 series, mentioned by the Third Assistant Postmaster General in a recent interview.”

A final official report of quantities issued was included as a table, reproduced here, in the fiscal year 1909 report of Third Assistant Postmaster General Lawshe to the president of the United States dated Oct. 30, 1909, published in 1910 by the Government Printing Office. It again verified the total number of imperforate 4¢ Grant stamps as 10,000. With the quantity confirmed, documented by BEP invoices and the POD fiscal year report, collectors were optimistic that they might be able to locate unused supplies.

In the March 1910 issue of The Stamp Journal, Missouri coil stamp specialist Vinton E. Sisson wrote: “The recent find in Detroit of the 4c Schermack perforation, seems to prove conclusively that it was issued imperforate, and if so this stamp in pairs or blocks in P.O. condition is destined to be the rarity of rarities of Uncle Sam’s postage stamps.”

Alas, Sisson was too optimistic. There are no blocks or fully imperforate pairs of Scott 314A. But the May 14, 1910, Mekeel’s, two days past the second anniversary of the imperforate 4¢ Grant issue date, quoted Detroit collector Herman W. Boers: “There is a person here who has had twenty of the stamps from a roll but used all of them up except a strip of five now in his possession. An offer of a large amount has been refused for the strip.”

The quantity of 20 was wrong, but the lucky man who possessed the stamps had a penchant for dispensing false, deceptive, and misleading information that has burdened the history of Scott 314A ever since.

KARL KOSLOWSKI’S PURCHASE OF UNUSED 4¢ GRANT SCHERMACKS

A Detroit stamp collector named Karl Koslowski (pronounced koz-LOFF-skee) had bought 50 of the stamps in unused condition from the Winfield firm in May 1908, just as he was departing Detroit for an extended visit to Latvia, the land of his birth. All unused examples of the stamp that exist today are survivors of Koslowski’s purchase, as are three of four known covers, both off-cover used multiples, and some used singles.

At the time Koslowski obtained his 50 stamps and set sail for Europe, he had no reason to expect that they would become rarities. Upon his return to the United States, after learning that his were the only ones available to collectors, he published various accounts of how he had obtained them in several philatelic publications.

Later in life he became a stamp dealer. Retelling the story of the 4¢ Schermacks became his way of keeping his name before the stamp hobby. Unfortunately, Koslowski’s stories are inconsistent with one another and with the available evidence.

Incorrect or incomplete information frequently accompanied Scott 314A stamps when they were displayed at philatelic exhibitions. The cumulative result was that much of what experts thought they knew about 4¢ Grant stamps with Schermack type III perforations was a hodgepodge of fact and fancy.

I tried to set the record straight in my article titled “The Rare 4-cent Schermack Coil Stamp” in the May 1994 American Philatelist. For a long time afterward dealers and exhibitors used that as their reference. Gradually, most of the misinformation that had been so widespread ceased to hold sway as the truth about these stamps became known.

More than two decades have passed since that publication. During the intervening years more facts have come to light, so this seems like an excellent time to update and retell the story, which entered its dramatic stage in the summer of 1910, more than two years after the stamps had been issued.

Koslowski had joined the APS that year and brought examples of the stamps to the APS annual meeting in August, which conveniently was held in Detroit. His first-hand account, which falsely stated that collectors had “entirely overlooked” the imperforate 4¢ Grant stamps, appeared in the Oct. 21, 1910, issue of Philadelphia Stamp News.

He wrote that they had been issued “almost a year” after imperforate 5¢ stamps. In reality, the first 10,000 imperforate 5¢ Lincoln stamps had been issued on March 30, 1908, followed by 2,000 more on April 4 — less than seven weeks before Scott 314A was issued.

As Koslowski told the story at that time, the Schermack Co. acquired the imperforate 4¢ Grant stamps on Friday, May 15, 1908, and processed them into coils that same day. He said he saw them first as imperforate sheets and watched as they were punched, slit, and coiled. But his article misdescribed the Schermack coil manufacturing system. His erroneous description reads:

First the sheets were trimmed of the end and right side margins, then cut into strips and pasted together into one long strip with the left side margin bent under, and used as a hinge and with a special machine, worked on the same principal [sic] as a sewing machine, cut with the private perforation and rolled up ready for use in the mailing machine. The perforation is now known as Schermack No. 3. All this was done in my presence, and the stamps were delivered to their customers on the same day.

Howard reported the actual method. He quoted a letter from the Schermack firm’s general manager W.F. Schwenger that explained the sequence: “These large 400 (subject) sheets were pasted together and run through machines for perforating and one row clear across was perforated at each operation, the coiling and stripping being done after the perforating but on the same machine.”

After punching slot perforations in vertical columns across all 20 rows of stamps and slitting the sheets horizontally between each row, the strips were rolled up into coils of 1,000 or 3,000 stamps with the gum side facing out.

It’s impossible to say whether Koslowski’s memory had lapsed over the two and a half years between obtaining his stamps and telling his story, or whether he simply made it up to make it seem as though he had witnessed the process. But that was not his worst fabrication.

He also wrote, perhaps hoping to inflate his personal image and importance among collectors, “As yet not even the Postoffice authorities have given a correct account of the number of this variety that were issued in imperforate form.” As noted previously, POD and BEP officials had compiled and circulated exact, unambiguous figures in January 1909 and on three subsequent occasions, and had published them in a report to the president.

As if to rebuke Koslowski’s reckless assertion quickly before it could gain undeserved credibility, J. Murray Bartels, after again consulting official records, wrote in the Dec. 15, 1910, issue of The Philatelic Gazette, “On May 15, 1908, twenty-five sheets of 400 each of the 4c stamp in imperforate condition, a total of 10,000 copies, arrived at the Detroit post office and this constitutes the entire issue.”

Koslowski reported that he had obtained from the Schermack Co. some stamps “that were cut close at the top or bottom, or the hyphen holes were cut too far into the stamps.” He had used most of those as postage, believing he would be able to acquire more at a later time, but he kept a few of the best examples in mint condition.

Many years later, Koslowski told a different story, embellished with new details, much like a fisherman’s fable about the catch that grew longer, stronger, and more tiring to reel in upon each recitation, but he no longer claimed to have watched as the sheets were being perforated and processed into coils.

At the 1947 meeting of the American Philatelic Congress in Detroit, he said that the Schermack firm’s bookkeeper had lived in the same house he did and that he frequently had visited the young man at his workplace, which was located near their residence. On Wednesday, May 27, 1908, Koslowski stopped at the Schermack office to bid adieu to his friends, because he was leaving for Europe the next day.

While he was at the office, Schermack’s treasurer returned from the post office with the bundle of 4¢ imperforate sheets. He offered to sell one full sheet to Koslowski, but Koslowski declined, wanting to keep the $16 for his trip.

At home that evening he had second thoughts. He returned early the next morning, May 28, to see if he could buy the stamps, but the stamps were gone. “They had all been delivered the very afternoon soon after I had left the plant.”

He learned (incorrectly, as it turned out) that the processed stamps had been delivered to two firms. Hamilton Carhartt was too far away to consider, so he went instead to the Winfield Co. and persuaded the mail clerk there to sell him 50 stamps. “Grabbing my purchase, I was on my way just in time to get aboard [a train] and wave good-bye to old Detroit.” (In reality Winfield was the printer and mail contractor for both Hamilton Carhartt and Burroughs; no stamps were delivered to either of the contracting firms.)

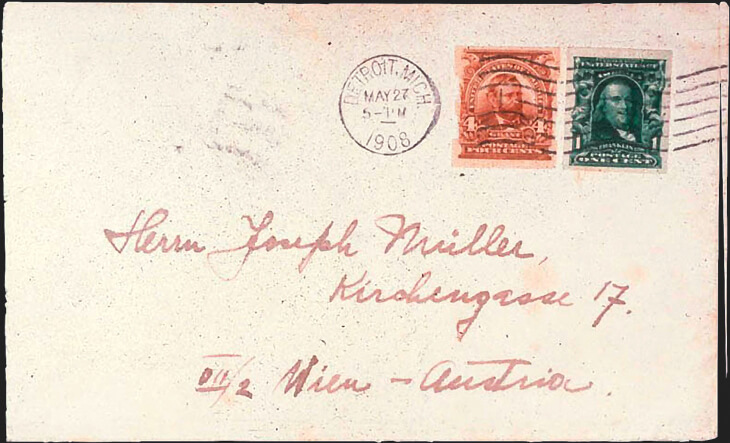

When Weekly Philatelic Gossip of Dec. 2, 1950, reprinted that version of Koslowski’s story, he attempted to document his departure date as the day he had acquired the stamps by illustrating a postcard he had sent from Buffalo to Detroit on May 28. But a cover Koslowski had mailed from Detroit to fellow stamp collector Joseph Mueller in Austria on May 27, 1908, the day before he left for Europe, proved that Koslowski was in possession of the stamps at least one day earlier than his 1947 Congress Book memoir stated.

The franking on that cover — one imperforate 4¢ Grant stamp with Schermack perforations and one imperforate green 1¢ Benjamin Franklin stamp (Scott 314) — combined to equal the 5¢ international single-letter rate to member countries of the Universal Postal Union. It is the earliest documented use of Scott 314A.

Spencer Anderson, a well-known Nassau Street stamp dealer from the 1920s to the 1940s, had offered the cover for sale priced at $875 in a full-page advertisement in the Dec. 20, 1941, issue of Stamps magazine.

To the best of my knowledge the cover appeared most recently in Siegel’s April 23, 1983, Rarities of the World sale, where it realized $20,000 plus a 10 percent buyer’s premium, total sale price $22,000.

The philatelic verdict on Koslowski is at best ambiguous. Collectors owe him a debt of gratitude for obtaining and preserving the only unused examples of the scarce imperforate 4¢ Grant stamps, and the only used multiples.

But his chronic failure to tell the truth about their origin, either because his memory played tricks on him, or because he intentionally misrepresented and embroidered the facts, or both, has tainted his legacy.

THE ONLY KNOWN COMMERCIAL COVER FRANKED WITH A 4¢ GRANT SCHERMACK STAMP

Fred R. Schmalzriedt was the most dedicated and trustworthy contemporaneous scholar who searched for, studied, and reported on the imperforate 4¢ Grant. He was nationally prominent in the stamp hobby, a life member of APS who served a term as the society’s attorney, also counsel for the Association of Stamp Dealers of America, and president of the Detroit Philatelic Society.

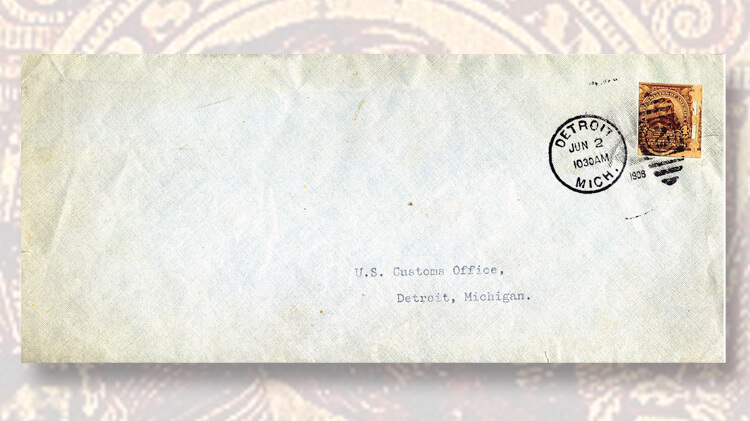

In December 1910 Schmalzriedt acquired an example of the stamp on a commercially used cover. He told the story of that cover in the Jan. 7, 1911, Mekeel’s:

I heard of a young man who took two covers containing four-cent imperforates from a wastebasket in the office in which he was employed. He took them home with him and on the same day removed one, which is perfectly centered, from the cover. The other, which is poorly centered and shows part of the next stamp on the right, he left on cover. He did not notice anything unusual about the stamps until about a year after his discovery but even then did not know that they had any particular value; and it was only through my purchase of the strip [of five for $300] referred to previously that he became aware of the value of his find. Both of these stamps are now in my collection. The cover is in a pale blue linen envelope, 9 3/8 by 4 1/8 inches in size, bearing no return card. The envelopes were sealed when sent out and apparently contained a circular 3 3/8 by 8 3/4 inches in size, which must have been of heavy paper, as the creases show very plainly in the envelope. The date of the cancellation is June 2, 1908, 10:30 a.m., and the place is the main post office in Detroit.

More than 25 years later, Schmalzriedt provided additional information in a letter to Max G. Johl, author of The United States Stamps of the 20th Century. Despite the lack of a corner card or contents, he said it had contained Hamilton Carhartt advertising matter:

My cover was addressed to the U.S. Customs Office at Detroit, Michigan, and pulled out of the wastepaper basket by a messenger. He claims that three envelopes, all alike, came there and that he got all of them. He removed one from the cover and I purchased that as well as his cover. He has never been able to locate the other cover, although he and his father, who was a clerk in our Probate Court, both always insisted that they originally had three.

Schmalzriedt owned the cover until he sold his Michigan postal history collection at a May 24, 1957, John A. Fox auction sale. The presale estimate for lot 466 was $3,500, so the $775 hammer price might have disappointed Schmalzriedt even though it was more than 30 times the price he had paid for it.

The cover next appeared at the May 21-30, 1966, Sixth International Philatelic Exhibition in Washington. It was part of an exhibit titled “United States Regular Series of 1902” entered by the husband-wife team of Dr. Robert S. and Judith Breakey of Lansing, Mich., which won a silver medal.

Breakey was a retired urologist. In the society pages of the local paper, the Breakeys were recognized not only as civic leaders and as patrons of the arts, but also as well-known stamp collectors. Herman Herst Jr. sold the Breakey collection in his April 11-12, 1972, auction sale. The 4¢ Schermack cover realized $1,800.

The buyer was Robert L. Markovits. It next appeared in the Shreves Philatelic Galleries May 30, 1996, sale of The Lawrence S. Fisher Collection of Classic United States First Day Covers and Earliest Known Usages, where it realized $60,000 plus 10 percent buyer’s premium, total $66,000.

Fisher had never owned that cover; he died several years before the Breakey sale. But Markovits curated the Fisher sale and included in it important covers he had acquired after Fisher’s death.

The cover was next a showpiece in Roger S. Brody’s exhibit of 1902 series stamps and covers until Shreves sold his collection at a Dec. 6, 2002, name sale. The cover realized $160,000 plus 10 percent buyer’s premium, total $176,000.

Although more than 9,950 4¢ Grant stamps with Schermack type III perforations were mailed, no other full cover from either of the commercial mailings has survived for philatelic posterity. This one is an iconic rarity of United States postal history.

However, Philadelphia dealer Philip H. Ward Jr. offered for sale a remnant described as “a piece of cover from Burroughs Adding Machine Co.” — a 4¢ Schermack on the upper right corner section of an envelope canceled June 19, 1908, at Detroit — in the May 1934 issue of Ward’s Philatelic News. The Philatelic Foundation certified it as genuine in 1957, and it was last recorded in an April 14, 1964, J.&H. Stolow auction sale.

CLYDE JENNINGS PUT SCOTT 314A IN PERSPECTIVE 50 YEARS AGO

At a March 2-3, 1960, sale, John A. Fox sold an attractive used example of Scott 314A with a guideline at the right, certified as genuine by the American Philatelic Expertizing Service (APEX). Clyde Jennings, a colorful and flamboyant philatelic raconteur who specialized in collecting canceled U.S. stamps, bought it for $630.

At a Jan. 18, 1967, meeting of the Collectors Club, he showed pages from his “substantially complete” collection of United States stamps on printed album pages. In the May 1967 Collectors Club Philatelist, the club’s rapporteur recorded “one of the most unusual displays seen in this club for a long time”:

There are five of what appear to be common postage stamps with a total face value of all of 9 cents. It is urged that you look up the total 1967 Scott Catalogue value of U.S. Nos. 594, 544, 596, 613, and 314A. Real U.S. 20th century rarities! …

This one page has about the rarest of all the United States stamps. The condition of each copy is possibly as fine as they come; each one has a certificate with the Philatelic Foundation Expert Committee’s opinion that it is genuine.

Scott 594 is the green 1¢ Franklin rotary press coil waste stamp of 1923. Scott 544, 596, and 613 are rotary press sheet waste stamps — the green 1¢ Washington issue of 1922, the green 1¢ Franklin issue of 1923, and the black 2¢ Warren G. Harding Memorial stamp of 1923. Jennings was right to place Scott 314A with those others in the top tier of scarcity and desirability.

(To fill out the list of elite 20th-century U.S. stamps, I would add horizontally perforated [vertical format] green 1¢ Franklin and carmine 2¢ Washington 1902 series government coil stamps, Scott 316 and 321, and the privately perforated Scott 482A Schermack.)

THE UNIQUE 4¢ GRANT SCHERMACK COIL STRIP

Schmalzriedt had bought Koslowski’s unused strip of five for $300 in December 1910. More than any other item, that rarity had made Koslowski a celebrity in the first place and remained linked to his public image for the rest of his life.

From Schmalzriedt the strip found its way into the collection of the legendary Col. Green, best known for his 1918 purchase of the complete 100-stamp sheet of the bicolor 24¢ Curtiss Jenny airmail with inverted center, Scott C3a, the famous Inverted Jenny error. The 4¢ Schermack strip realized $4,300 when it appeared in Part 26 of The Colonel E. H. R. Green Collection of Rare Postage Stamps held by Harmer, Rooke & Co., March 25-29, 1946.

The picture of the strip of five shown here is reproduced from the Harmer, Rooke sale catalog. In 1964, the Raymond Weill Co. sold the mint strip of five to Josiah Lilly Jr. for $17,000. At Siegel’s Feb. 20, 1968, Part VII sale of the Lilly collection it realized $26,000. The buyer was Benjamin D. Phillips, who died eight months later. The Weill brothers, who also had built Phillips’ collection, bought it back shortly before his death.

In one of the oddest embarrassments of philatelic journalism, Ward wrote in 1935 that the strip of five had been cut into two pairs and a single, then followed up with his apology when other writers pointed out his mistake. Several years afterward, he republished the same article, complete with the same error, and retracted it a few weeks later. Unfortunately Ward’s mistake became prophecy half a century after he first committed it.

The strip of five last came to market at Siegel’s April 20, 1985, Rarities of the World sale. This was the description of lot 263:

4c brown imperforate, Schermack Ty. III Private Vending Machine Perforations (314A). Horizontal Strip of Five, Fresh. Two Stamps Mint, light thinning left stamp, otherwise Extremely Fine, The Largest Known Multiple, A Fantastic Showpiece, ex-Green.

It realized $75,000 plus a 10 percent buyer’s premium, total $82,500. The buyer was Boston stamp dealer Jack Molesworth. Molesworth cut off the thinned stamp at the left end and submitted the remaining strip of four to the Philatelic Foundation, which certified it as genuine with original gum and mentioned no faults.

Molesworth must have thought that a sound unused strip of four would have greater appeal to a prospective buyer than a strip of five with one faulty stamp, but he was unable to find a customer for it. Next he cut the strip of four into two pairs, which did find homes in elite collections. After the pair that had been positions 2 and 3 of the strip sold for $105,000 plus 10 percent buyer’s premium — total $115,500 — at Siegel’s October 8, 1998, sale of the Robert Zoellner collection, Connecticut stamp dealer Larry Volovski cut that one into two single stamps.

Today the largest surviving multiples of Scott 314A are two used strips of three, one off-cover, the other on the most visually striking showpiece cover of this issue. Both originated with Koslowski.

TWO MORE KARL KOSLOWSKI COVERS

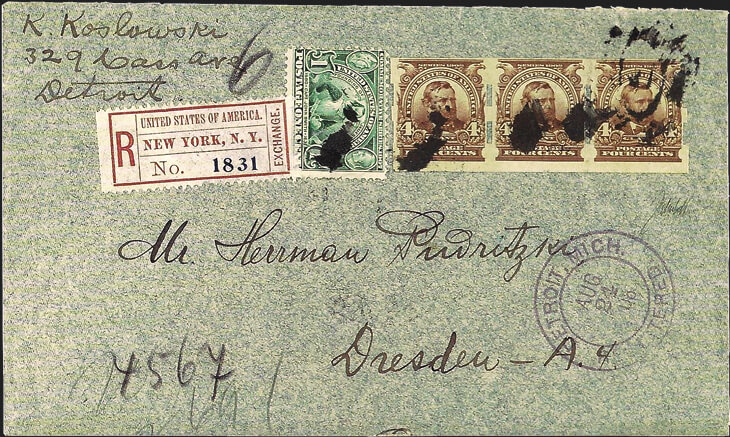

The most stunningly photogenic cover that features Scott 314A is a registered cover posted Aug. 14, 1908, to Dresden, Germany. It is franked with a strip of three 4¢ Grant Schermack stamps and a green 1¢ Jamestown Exhibition commemorative (Scott 328), which represented 5¢ letter postage plus 8¢ for the registry fee. Koslowski had mailed it upon his return to Detroit from his trip to Latvia.

Provenance notes Markovits shared with me about 20 years ago show that the cover was in Seymour H. Kaplan’s collection in the 1960s. It appeared in Siegel’s March 24, 1970, Rarities of the World sale (memorable for achieving a then-record $280,000 realization for the unique 1856 1¢ Magenta of British Guiana). The Koslowski cover sold for $8,500. Six years later, described as “Probably the Rarest 20th Century U.S. Cover in Existence,” Siegel sold it again, this time hammered down for $11,500 at an Oct. 19, 1976, sale.

The cover’s next appearance was in a Nov. 19-23, 1985, sale held in New York City by the Swiss auctioneer David Feldman S.A., where it sold for $41,400 (a hammer price of $36,000 plus 15 percent buyer’s commission). It became a featured item in Donna O’Keefe’s Jan. 26, 1986, Philatelic Gems column titled “Rarity among Schermack perforated issues.” (She is Linn’s editor Donna Houseman now.)

The buyer was Texas plastic surgeon, global humanitarian, and stamp collector Joseph Agris M.D., who included it in his gold medal exhibit of United States coil issues.

I met Agris at the Ameripex 86 international philatelic exhibition in Chicago. (He and I both collected and wrote books about then-current plate-number coil stamps.) His business card pictured an unused Scott 314A stamp in color.

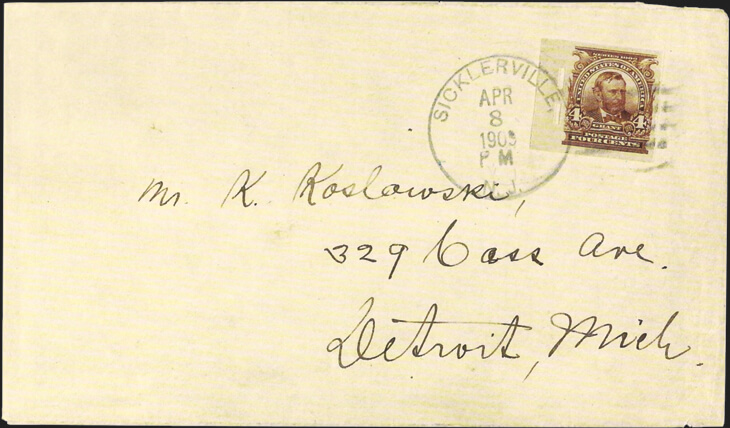

The Agris exhibit also included a cover that had been the first to be sold, in December 1910, before any of the others had been reported. The stamp is a left margin example with a clear April 8, 1909, cancel of Sicklerville, N.J., on a return envelope addressed to Koslowski, backstamped on the same date with a Philadelphia transit postmark.

Koslowski had sent a parcel to his brother in Sicklerville franked with a strip of three 4¢ Grant Schermack stamps. He enclosed this envelope for his brother to return the canceled strip, which today is the largest off-cover multiple of the stamp.

Koslowski sold the cover to William C. Rhodes of Cleveland for $50. The cover soon reappeared at a June 1911 Hugh M. Clark auction sale, where it realized $60.50. Cleveland tycoon George H. Worthington owned it next, until he ran into financial difficulties. At the first J.C. Morgenthau auction of Worthington’s collection Aug. 21-23, 1917, it realized $150. According to Philadelphia dealer Eugene Klein’s marginal note in the Worthington sale catalog, the buyer was Cameron Sperling.

Markovits recorded the cover as part of Kaplan’s collection in the 1960s. It appeared in Siegel’s Feb. 24, 1965, Rarities of the World sale, where it realized $3,100, and again in the firm’s Nov. 25-26, 1969, sale where it realized only $800. (Or was that a typographical error on the prices realized sheet?)

In the April 20, 1985, Rarities sale, where it realized $22,000 plus a 10 percent buyer’s premium, total $24,200, Siegel described it as “Undoubtedly the best used example either on or off cover.”

When Agris submitted the cover to the APEX for a certificate, the APS expert committee reported that the stamp had a small crease in the top left margin. That indentation is visible in the catalog photograph. I believe it was impressed at the edge of the original sheet by a gripper on the Schermack perforator, so I would not regard it as a fault.

Shreves sold the Agris collection at a special Sept. 5, 1997, name sale. The cover to Dresden realized $200,000 plus 10 percent buyer’s premium, total $220,000. The cover from Sicklerville realized $110,000 plus 10 percent buyer’s premium, total $121,000.

FAKE SCOTT 314A STAMPS

With prices rapidly rising and few genuine imperforate 4¢ Grant stamps available to meet the demand, unscrupulous sellers searched for ordinary perforated 4¢ Grant sheet stamps (Scott 303) with extra-large margins that could be altered to resemble genuine Schermacks. In the Jan. 20, 1911, issue of Philadelphia Stamp News, Koslowski wrote about one he had seen and added a warning:

… I have also seen a copy that was cut from a perforated stamp but it was a very poor job, and there is little danger that these stamps can be faked.

Any one with a slight knowledge of these perforations can tell by glancing at it whether or not it is the real Schermack. At the same time I would warn buyers of these stamps to ascertain if they are genuine before closing a deal in case of single stamps. A pair, of course, is genuine in every instance.

As ever, Koslowski was too glib. More than a glance is necessary to authenticate Scott 314A. In 1947 he added another cautionary observation:

All of those 4c “Grants” as I recall it, were of the dark brown shade, all coming from the same printing. Recently while on a visit to Mobile, Alabama, I was shown a copy in very light yellow brown. Naturally, I could not consider it seriously as a true Schermack.

Steven R. Belasco appended to his article “Characteristics of Genuine Vending and Affixing Machine Perforations (Part II)” in the March 1982 United States Specialist a table of stamps with Schermack perforations that had been examined by the Philatelic Foundation. At that time, 65 stamps had been submitted as Scott 314A, and of those, 24 were certified as genuine and 41 as fake. (On occasion the Philatelic Foundation has been unable to determine the authenticity of stamps submitted at Scott 314A and has declined to state opinions on them.)

In his 2009 book Guide to United States Vending and Affixing Machine Perforations 1907-1927, Belasco wrote:

For Scott No. 314A, all the counterfeits come from the regular perforated stamp (Scott No. 303). The perforations are trimmed off to fake an imperforate stamp and then fake Schermack Type III perforations are added. The most dangerous fakes come from copies of Scott No. 303 with a straight edge, and in particular the positions that have two straight edges. The straight edges of the regular sheet stamps were cut along the guidelines of the sheet, so if a guideline shows on the edge of a used single, it requires extra care to evaluate if the stamp is a genuine Schermack Type III. Color is another important factor in evaluating this stamp. Genuine examples are a true brown color, rather than a yellow-, red-, or orange-brown.

Two fakes of Scott 314A examined by the Philatelic Foundation are pictured here. The older one, made by adding counterfeit Schermack type III perforations to a 4¢ Grant die proof (listed in today’s Scott U.S. Specialized catalog as No. 303P2), is extraordinary. The other one was altered to resemble Scott 314A by the more typical forger’s method that Belasco described.

In the May 9, 1932, Mekeel’s, Warren L. Babcock described an unusual fake made from a Scott 303 perforated sheet stamp that simulated a fully imperforate stamp without Schermack perforations added. Besides being the wrong shade of brown, he wrote:

It is on a piece of manila wrapper with Memphis [postmark]. … While the stamp had gloriously large margins, it undoubtedly was trimmed on three sides with the fourth a straight edge. The cancellation was partially redrawn. The stamp had obviously replaced another on the piece of wrapper. The stamp is said to have come from one of the largest U.S. specialized collections now being dispersed.

A philatelic forger who is known to have created at least one fake Scott 314A was 1960s Massachusetts stamp dealer and writer Richard A. Kiusalas. He invented the United States Specialist Gauge and a counterpart perforation gauge for expert identification of Canadian stamps, but he also deceptively altered stamps and added counterfeit overprints to genuine stamps. Kiusalas was notorious for reperforations that were difficult to detect, and he possessed a steel punch that simulated Schermack type III hyphen-hole perforations.

LATER OFFICIAL DOCUMENTATION

A December 1916 report prepared by the BEP for Third Assistant Postmaster General Alexander M. Dockery provided the dates of issue for every United States stamp issued since 1901, including the imperforates. That document reconfirmed May 12, 1908, as the date of issue for the imperforate 4¢ Grant stamp.

That report became the reference for most 1901 through 1916 stamp issue dates published by Johl in his book and by the Scott catalog. As recently as 1994 the original report was in the Third Assistant Postmaster General files at the Smithsonian Institution, but a recent search by the National Postal Museum staff has failed to locate it. Fortunately, the essential details appeared in a front-page article, “Chronology of Adhesive Postal Issues of the U.S. During the Twentieth Century” by C. Edward Wright in the Jan. 20, 1917, issue of Mekeel’s.

Karl Koslowski died in 1954 at age 76, and Fred Schmalzriedt died in 1960 at age 80. Both men regarded the 4¢ Grant stamp with Schermack perforations as their great philatelic adventure, and both considered it an outstanding rarity. Neither man lived long enough to see the stamp achieve four-figure realizations except for one item — the mint strip of five that Koslowski had sold to Schmalzriedt for $300 in 1910, which has not survived intact.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When I first studied and wrote the story of Scott 314A in 1994, Gini Horn, Susan Dixon, and Kathleen Wunderly located and retrieved many published references at the American Philatelic Research Library. Cecilia Wertheimer, curator of the Historical Resource Center at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and her assistant Rochelle D. Edmonds provided copies of BEP Postage Stamps order book pages from Sept. 21, 1906, to May 26, 1909. Kurt and Joann Lenz verified historical information in Detroit. Herbert Trenchard guided me to pertinent auction sale records. Mercer Bristow supplied information from the records of the American Philatelic Expertizing Service, and William T. Crowe did likewise from the Philatelic Foundation.

Edward J. Siskin shared his documentation on the earliest and other uses on cover, and Roger S. Brody sent material he had gathered as chairman of the Second Bureau Issue Committee of the Bureau Issues Association (since renamed the United States Stamp Society).

This article has built on that foundation. In 1997 Wertheimer sent copies of additional pages from BEP Postage Stamp order books, up to Sept. 14, 1910. Her successor, Hallie P. Brooker, assisted me more recently. I have also benefited from assistance provided by APRL staff members Tara Murray, Scott Tiffney, Krystal Harter, and Fred Baumann, and APRL volunteer Ellen S. Peachey; Philatelic Foundation consultant curator Lewis Kaufman; Scott R. Trepel, president of Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries; National Postal Museum curator of philately Daniel A. Piazza; U.S. Postal Service historian Jennifer M. Lynch; Melvin Getlan, chairman of the United States Stamp Society’s Vending and Affixing Machine Perforations Committee; Steven R. Belasco, former chairman of that committee, who died in 2012; and from provenance records compiled by Robert L. Markovits, who died in 2015.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers