World Stamps

The man who proposed U.S. postage stamps seven years before they were first produced

By Wayne L. Youngblood

The devil is in the details, as the old adage goes.

Such is the case with the first government-sanctioned reproduction of a postage stamp and Daniel Webster’s forward-thinking, but failed, resolution for uniform and prepaid postage.

Ironically (for those familiar with The Devil and Daniel Webster, Stephen Vincent Benet’s fictional story involving the famous lawyer), it would take an additional seven years for Webster’s proposal to be adopted.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

It is easy for us today to simply take for granted the relatively low cost and swift movement of the mails, as well as the high-quality reproduction of postage stamps in philatelic journals and other publications. But these were not things to be taken for granted during the mid-19th century.

Both intersected briefly in 1840, during the infancy of postage stamps, when the first session of the 26th Congress was convening. Among the political heavy-hitters in the Senate at the time were Henry Clay (Whig-Ky.), Daniel Webster (W-Mass.), Thomas Hart Benton (D-Mo.), Franklin Pierce (D-N.H.), James Buchanan (D-Pa.), and John C. Calhoun (D-S.C.).

Just weeks after the May 1, 1840, issuance of Great Britain’s Penny Black adhesive stamp and Mulready envelope (both became valid for postal use May 6), the very first government-sanctioned reproduction appeared in the United States, but had nothing to do with the release of the stamps themselves.

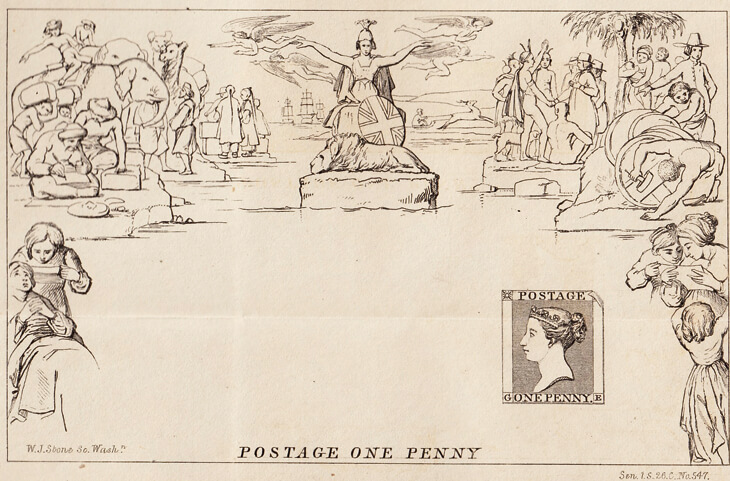

The full-sized facsimile, a gorgeous copperplate engraving, is shown in the first illustration. It features the design of the Mulready envelope, with an unfinished Penny Black inset at lower right.

The facsimile was published in the Senate Resolutions (26th Congress, First Session, June 10, 1840) as part of Webster’s resolution.

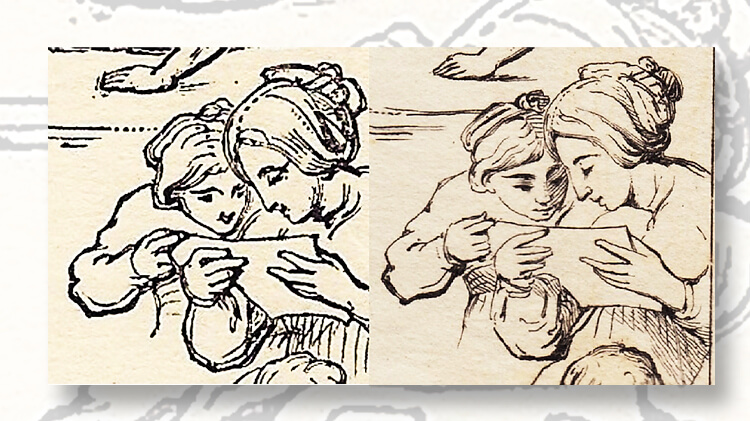

The detailed copperplate engraving was created by William J. Stone of Washington, D.C. It is arguably better than the original Mulready envelope, as can be seen from the same detail taken from the envelope, left, and the engraving, right, in the nearby illustration.

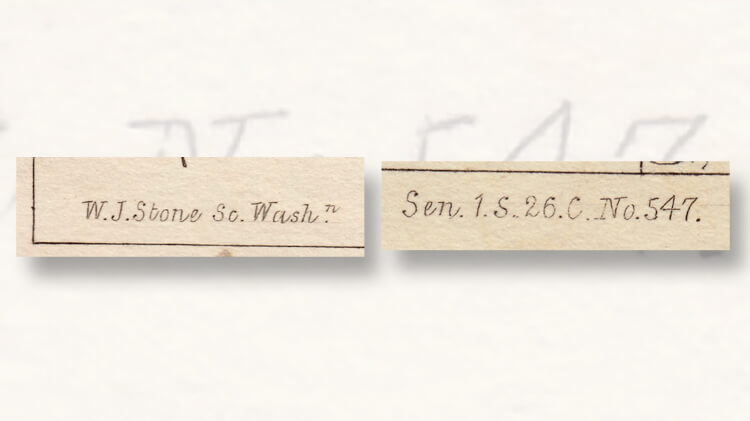

Stone, whose imprint details from the bottom-left and bottom-right corners of the reproduction are shown enlarged in the third photo, had distinguished himself for having engraved a full-sized facsimile of the Declaration of Independence for John Quincy Adams in 1820-23.

Adams, wishing to preserve the then-aging document for posterity, commissioned Stone, and 200 copies were printed on parchment. The Declaration copperplate, which took him three years to complete, is on permanent display in the National Archives rotunda in Washington, D.C.

By commissioning such a high-quality engraving of the Mulready envelope on very short notice for the Senate resolution, Webster obviously believed in his proposal.

Engaging the services of Stone was likely a fairly simple matter for Webster, because the two (along with John Quincy Adams and Peter Force) were among the 12 co-founders of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science in May 1840, which later became a part of the Smithsonian Institution.

At the time, the U.S. Post Office Department was plagued by steep and mounting annual deficits that were beginning to threaten its existence.

Chief among the reasons for these deficits was the complex and expensive system of postage rates, as well as the practice of accepting unpaid letters for delivery.

These items, processed and carried extremely long distances in some cases, were frequently refused by the recipient and returned to Washington, D.C., as undeliverable, with the Post Office Department assuming all related costs.

In some cases, recipients couldn’t afford the postage; in others, it was a way to hear that a loved one was safe without having to pay.

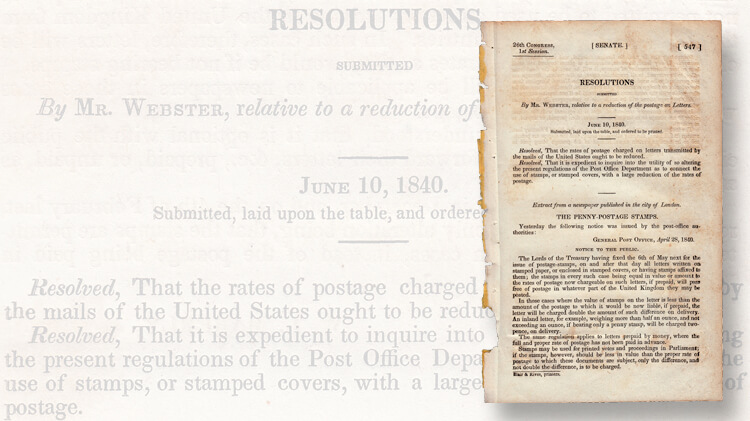

Webster’s specific resolution, the first page of which is shown in the last photo, read: “Resolved, That the rates of postage charged on letters transmitted by the mails of the United States ought to be reduced.

“Resolved, That it is expedient to inquire into the utility of so altering the present regulations of the Post Office Department as to connect the use of stamps, or stamped covers, with a large reduction in the rates of postage.”

By literally illustrating his point, Webster used the special engraving by Stone that accompanied the resolution.

Webster’s resolution ultimately died without action, as many of those in Congress at the time feared that lowering postage rates would further increase the department’s revenue shortfalls.

In 1845, with the Postal Act of 1845, postage rates were simplified and reduced tremendously to the basic 5¢ (for mail sent fewer than 300 miles) and 10¢ (for longer distances), rates in effect two years later, when the first United States postage stamps were released.

The finely engraved Penny Black and Mulready facsimilies remain as the only tangible evidence of Webster’s progressive proposal.

An example of the proposal and facsimile, part of the Royal Philatelic Collection, were exhibited by the National Postal Museum in 2004. It is reported that only a couple of examples are known in private hands.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers