World Stamps

Who was Milan Stefanik and why is he on stamps of three nations?

By Rick Miller

Shown in the first slide above are three stamps commemorating astronomer, philosopher, soldier, and statesman Gen. Milan Stefanik.

The 50-halleru green stamp perforated gauge 10, left, was issued May 19, 1935. The 60h dull violet stamp in the center is perforated gauge 12½ and was issued in 1936. Issued March 30, 1939, the 60-halierov dark blue stamp at right is also perforated gauge 12½.

All three stamps are inscribed “Ceskoslovensko,” but the stamps at left and center are Czechoslovakia stamps (Scott 208 and 217), while the stamp at right is from Slovakia (23A).

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

The Czechs and Slovaks are Western Slavic people who began moving into Central Europe from the Black Sea area in the sixth century.

The Czech language and the Slovak language form a dialect continuum in which most dialects are mutually intelligible.

Culturally, the Czechs have been a more urban people with a fairly strong tradition of religious nonconformity, while the Slovaks have been more rural and agrarian and more conservatively loyal to the Roman Catholic Church.

As part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918, the Czech lands were governed by Austria, while Hungary ruled in the Slovak lands. Before independence, the Czech lands were known as Bohemia and Moravia.

In 1918, it became obvious that the Dual Monarchy was losing World War I, which was likely to result in the fall of the Habsburg Empire. Czech and Slovak nationalists united in the Czechoslovak National Council to work for independence.

The council, which would evolve into the provisional government of independent Czechoslovakia, was primarily led by two Czechs, Thomas Garrigue Masaryk and Edward Benes; and one Slovak, Gen. Stefanik.

Milan Rastislav Stefanik was born July 21, 1880, in Kosariska, Slovakia. Atypically for a Slovak, he was a protestant and his father was a Lutheran pastor.

Educated in Slovakia through secondary school, he went to Prague in the Czech lands for his university education. At Charles University, he studied philosophy, astronomy, optics, mathematics, and physics. He received a doctorate in philosophy in 1904.

In 1904, Stefanik traveled to Paris and found employment at the Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, the leading observatory in the world at the time.

Through hard work and talent, he became acknowledged as one of the premier astronomers of his day. He traveled the world to view eclipses and other astronomical phenomenon, visiting South America, Central Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Tonga, Fiji, and Tahiti.

To observe astronomical phenomena without being obstructed by the thick sea level atmosphere, he became an accomplished mountain climber to view the heavens from the tops of mountains.

After accepting French citizenship in 1912, in his travels he served as an unofficial diplomat, working closely with French and foreign diplomatic personnel.

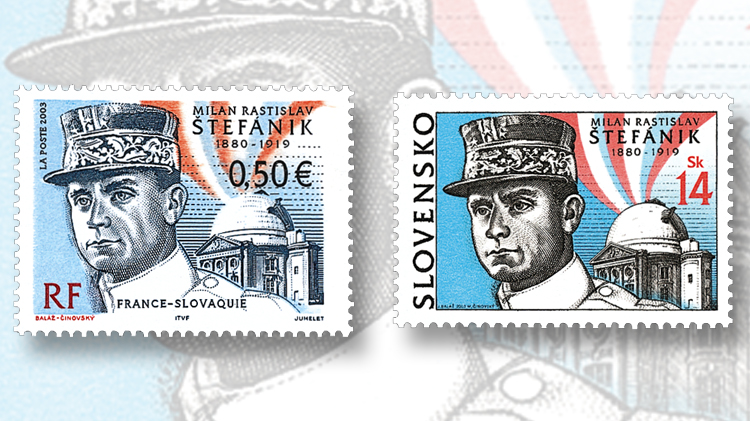

On May 3, 2003, France and Slovakia participated in a joint issue honoring Stefanik’s achievements as an astronomer. The French €0.50 stamp (Scott 2942), perforated 13¼, and the Slovakian 14-koruna stamp (Scott 428), perforated 11¾, are shown in the slider above.

The main building of the Observatoire de Paris-Meudon can be seen in the background. The red, white, and blue colors above the observatory represent both the French and Slovakian flags, as well as Stefanik’s work in spectral analysis of the sun’s corona.

World War I started in August 1914 with Austro-Hungary allied with Germany and the Central Powers. Stefanik saw the defeat of Austro-Hungary as a catalyst for Czechoslovakian independence.

Accepting a commission in the French army, he took aviation training and became a military pilot. He flew Farman reconnaissance aircraft on the Western Front and later, in 1915, on the Serbian Front.

He was a founding member of the Czechoslovak National Council in 1916 and served as its vice president. His diplomatic contacts from his time as an astronomer greatly aided the council’s work for Czechoslovak independence. He was promoted to the rank of general, and in 1917 was named a Grand Officier de Odre national de la Legion d’honneur.

In 1917, Stefanik began organizing Czech and Slovak prisoners of war in Italy and Russia who had been fighting for Austro-Hungary into pro-Allied Czechoslovak Legion troops.

This greatly enhanced the Czechoslovak National Council’s standing with the Allies and led directly to its recognition as the provisional government of independent Czechoslovakia.

The Bolshevik coup in Russia in November 1917 left the Czechoslovak Legion troops in Russia trapped behind Bolshevik lines. Stefanik worked for and organized their withdrawal eastward across Russia and Siberia to the Pacific coast for evacuation via Vladivostok.

While in Russia, the Czechoslovak Legion organized a postal system and even issued its own stamps. A Czechoslovak Legion Post 50-koruna Armored Railroad Car stamp (Scott 2) is also pictured above.

After independence was established, Stefanik served as minister of war in the Czechoslovakian government. He worked closely with the French and Italian military missions present in Czechoslovakia to help restore order and establish the country’s boundaries.

On May 4, 1919, he was flying home to Slovakia from Italy in an Italian military plane. The plane crashed while attempting to land near Bratislava, Slovakia, killing all four Italian crewmen and Stefanik.

The cause of the crash was never officially determined, but it could have been shot down by hostile Hungarian Communist forces or caused by pilot error or mechanical failure.

In May 1939, Slovakia issued a set of four Gen. Stefanik and Tomb stamps (Scott 34-37) to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his death.

The 40h stamp from the set (Scott 34) is illustrated in the slider above. The shooting star above the tomb represents both his career as an astronomer and his meteoric rise and fall.

In his lifetime, Stefanik was firmly committed to Czech and Slovak unity. He failed to foresee the inherent tensions in the union that would lead ultimately to its breakup in 1939 and again in 1993.

The Czechs were generally more urban, better educated, and less religious than the Slovaks. The Slovaks tended to resent what they saw as Czech domination of the government and other institutions in the republic.

When Nazi Germany liquidated what remained of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Slovakia became a nominally independent republic allied to the Germans.

The 60h dark blue Gen. Stefanik stamp shown in the first illustration had been prepared but not issued by the Czechoslovak postal authorities.

The Slovak government took possession of the stamps and issued them for use in the Slovakian postal system.

After Germany was defeated in 1945, the Czech and Slovak lands were reunited as Czechoslovakia, albeit under Soviet occupation. Under pressure from the Western Allies, the Soviets briefly tolerated a coalition unity government in Czechoslovakia.

Six Czechoslovakian definitive stamps in a set of 16 (Scott 293-304) issued during this period featured Stefanik. The 30h stamp from this set (Scott 293) is shown above.

On Feb. 25, 1948, the Soviet Union forced the resignation of President Edward Benes and the non-Communist members of his government, and Czechoslovakia became a one-party Communist dictatorship.

Communist rule in Czechoslovakia collapsed in 1989, once again exposing the fault lines between Czech and Slovak nationalism.

Attempts to reconcile differences were unsuccessful, and the republic was peacefully dissolved into its constituent parts effective Jan. 1, 1993.

Today, Stefanik is revered as a patriot and a pioneering astronomer in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and France.

The 1945 Czechoslovakian 30h Gen. Stefanik stamp (Scott 293) that is the last in the above slider was issued during the period when the Soviet Union tolerated a coalition unity government in Czechoslovakia.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers