World Stamps

The dual purpose of Geneva’s first cantonal stamp

Unveiling Classic Stamps — By Sergio Sismondo

For the past 15 or more centuries, Geneva has attracted streams of visitors and prospective residents. Many have settled there. Some might think the most pleasant lake and propitious weather in the valley were important inducements. This was probably part of the attraction, but when looking at the mix of migrants, it is possible to discern another set of factors.

Lake Geneva is surrounded by mountains and hills; it might have been more effectively defended against attackers than other, more open spaces. Geneva attracted moneyed folk seeking peace and security, for their property and for themselves. It attracted intellectuals, of all kinds — philosophers, playwrights, historians, mathematicians — seeking protection from thought police in other European countries.

Geneva also attracted religious leaders seeking freedom of speech, freedom of worship, and safety from those who would impose their brand by violent means. Geneva became a place of great prestige. To be a citizen of Geneva was something special. Economists and geographers would describe its principal characteristic to be its centrality — an intellectual and economic crossroads.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

The formal title of this city and its surroundings says that it is both a republic and a canton. It was proclaimed a republic in 1541, under the leadership of John Calvin, and was given a republican constitution (the “Edits civils”) two years later.

For a long time Geneva was seen as a partner and military ally of the Swiss Confederation, although it did not have the status of a canton. In 1815, having suffered the disasters of a French conquest and French revolutionary government, it chose to definitively become a canton, the 22nd in the Swiss Confederation, assuring the permanence of its ties to the others. Joining the confederation was Geneva’s proclamation of “never again.” Thus, its name continues to this date to be “The Republic and Canton of Geneva.”

Postal Reform

Great Britain was the first nation to introduce postage stamps for prepayment and to legislate the lowest possible rate of postage, uniformly applied to as many letters as possible, regardless of distance traveled.

The main foci of the British reforms were to aid businesses, to increase the number of letters written and posted, to eliminate certain frauds bothersome to the treasury, and to reduce the workload of postal employees.

Zurich was the second jurisdiction to introduce similar measures for essentially the same purposes. Postage stamps were issued March 1, 1843, as discussed in this Linn’s column posted online March 3.

Geneva, the most important and most advanced city in Switzerland, did not wish to lag behind its confreres of Zurich. Less than three months after Zurich stamps were issued to the public, a voice from Geneva was heard in the Grand Council speaking for postal reform, postage stamps, and prepayment of postage.

Professor Alphonse le Candolle had been a visitor in London in 1839 and had followed, of his own interest, the details of the government’s efforts to reduce the rate of postage, introduce the prepayment, and simplify the system for the benefit of the public and the administration. He was most impressed by the commitment of the British authorities to go the distance for the benefit of small and large businesses.

On May 22 ,1843, le Candolle addressed the council with lengthy remarks regarding the functioning of the postal system in Geneva, as contrasted to the new postal system of Great Britain. His address is fully recorded in the annals.

Le Candolle made essentially three recommedations: (1) to grant selected businesses the franchise for selling postage; (2) to introduce postage stamps; (3) to do everything possible to simplify collection and delivery so as to make the mail system more convenient to the general public. In his estimation, these three measures would lead to a great increase in the volume of mail of the Geneva canton.

He concluded his lengthy remarks with the following summarizing paragraph, which conveys the motivation behind his suggestions, and some of the “spirit of the time” in Geneva.

The “Petite Poste” or Cantonal Post seems to me to be destined to receive twice or three times as many letters as at present; but in order to reach that probable increase, the reduction of the rates, which are already moderate, does not appear to me to be the chief means. The aim will be more certainly attained by accelerating the delivery of letters, and by enabling everybody to prepay them without going out of his way for the purpose. I hope the Administration will consider the suggestions I have had the honour of submitting. To facilitate their examination, I deposit specimens of the labels and envelopes in use in England. For these I have to thank Judge Prevost and his brother, Mr. L. Prevost, Swiss Consul in London. The last named gentleman is so placed that he can give all such information that may be desired, and this he would no doubt furnish with the enlightened zeal he brings to bear upon the business affairs of his own country.”

The honorable member then deposited on the table two letter envelopes with the stamps used in England.

From there on, things moved rapidly. Within a day or two, the minutes of the meeting were forwarded to the Finance Department for their views.

On June 13, the Finance Department responded in detail with a document, still extant, that stated they disagreed with the granting franchises for selling stamps, but agreed wholeheartedly with the other objectives and the suggestions put forth for their achievement. Regarding issuing stamps for prepayment, they went so far as to say:

“The Department, without judging it necessary to state the reasons for its opinion, sees nothing that is not most beneficial in this measure which is already in vogue in England and at Zurich.”

On June 19, less than a week later, the Council of State held a meeting and issued the following orders:

(1) Recommends to the Grand Council to proceed with the production of postage stamps for prepayment of postage.

(2) That no changes of postal rates be made at this time.

(3) Recommends the Grand Council to commission the Administration to provide a detailed proposal for the production of stamps.

(4) It does not recommend the franchising for the distribution of postage stamps.

Accordingly, a contract for the printing of stamps was awarded to the firm Schmidt Lithographers, local printers in Geneva. The project moved rapidly.

On Sept. 26, the Council of State held a meeting and advised the Grand Council that the stamps for 5 centimes and 10c were ready and would be distributed through the post offices of Geneva and Carouge, and would be available to the public beginning Oct. 1, 1843.

On Wednesday, Sept. 27, posters were affixed in various locations throughout the city to inform the public of the new system of prepayment.

With characteristic Swiss efficiency, on Oct. 1, 1843, Geneva became the fourth nation-state in the world to issue postage stamps, after Great Britain, Zurich, and Brazil.

The Double Geneva

The first stamp issued by the canton was peculiar. It can be described as a 10-centime stamp that could be split to be used as two 5c stamps, or it can be described as two 5c stamps joined together so they could be readily used as a 10c stamp.

It made complete sense to create such a dual stamp because the postage rates remained unchanged by the executive edict: 5c for city letters and 10c for cantonal mail between towns or cities. The stamp (Scott 2L1) quickly became known as the “Double Geneva,” a name that it still has today.

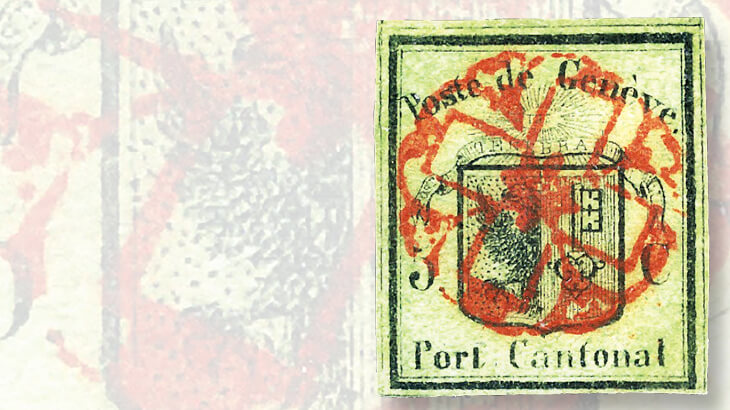

The double function of the stamps is reflected in the design. Each stamp bears the value “5.C,” and the pair is crowned by a cartouche with the insciption “10. PORT CANTONAL. Cent.” Thus both functions are clearly stated.

Each stamp has in the center the city’s shield divided into two halves. At right is the “key,” a symbol of the independence and security of the city; and at left is a large part of an eagle, which is awkwardly crowned.

Over the escutcheon is a ribbon with the inscription “POST TENEBRAS LUX,” which is a motto of the postal service (roughly: the post brings light to darkness). Above that is a tiny sunburst with the letters “JHS,” which is a reference to the Lord Jesus. Above and below are the inscriptions “Poste de Geneve” and “Port Cantonal.”

It was stated in the council’s edict of September that 60,000 Double Geneva stamps were to be printed. Each sheet would contain 100 stamps arranged in 10 rows of 10. Thus 600 sheets were printed. It was stated by expert philatelists that approximately 90 percent of the stamps were split, for local use. If that is correct, only 6,000 pairs were used or remained in unused condition at the time.

We can assume that a 10 percent survival rate, calculated for many other classic stamps, also holds for this stamp. We can accordingly estimate that no more than 600 pairs of Double Geneva stamps exist today, including, unused, used, fine, and damaged examples. The author has seen examples utterly destroyed by the passage of time and carelessness of handling.

Four months later, the Finance Department considered the sale of stamps to be insufficient. The public was apathetic regarding the innovations implemented. Sending letters unpaid was a habit hard to shake.

This reluctance to adopt the new method also was found in Great Britain, and later in France. The solution favored by those countries was to impose higher rates of postage due for letters sent unpaid.

Geneva’s Finance Department, however, suggested a more conciliatory method: the reduction of the price of the stamps. A resolution of Feb. 6,1844, stated that the 10c stamps would be sold for 8c, and the 5c stamps would be sold for 4c. The rates for unpaid letters would continue to be 10c and 5c, respectively.

Sales improved. In 1844, a total of 5,383 letters were mailed bearing the double stamp of 8c. Numbers were pointing in the right direction. After the price reduction took place in March, the number of prepaid letters in the 8c category was 427; in September 1844, the number of prepaid letters had reached 647. Still, the proportion of letters that were prepaid was only about 7 percent, from a total of about 77,000 for the whole canton for the year.

The Small Eagle

The postal reform implemented in 1843 was moving along in the right direction but more slowly than thought. Still, progress made during 1844 was encouraging, and the Grand Council, Finance Department, and the post office were all three of one mind: full steam ahead, this needs to be done, and the sooner the better.

Pressure was mounting from the public to reduce postal rates. On March 6, 1845, the Finance Department decided to respond to the public sentiment and proposed to the Grand Council a new schedule of reduced postal rates, as follows:

Article I called for letters below 1 ounce to be charged 5c for the whole canton; letters between 1 ounce and 3 ounces to be charged 10c for the whole canton. The rate for each additional ounce was 10c.

Article II stated that stamps would be sold singly for 5c each and 4 francs for 100.

The Grand Council met again March 14, 1845, and accepted Article I, with modification of the second article.

Article II read: “The Finance Department is authorized to order that 5 centimes stamps for the interior be sold at 4 centimes each.”

Within the next two or three days, a second contract was signed with the printers. The same firm was chosen. Schmidt began work on a new stamp, following instructions from the postmaster and introducing a few artistic improvements of his own.

He worked feverishly: artwork, master die, intermediary transfers, making the stone, acquiring the paper, the inks, the gum, and printing. Before April 1, Schmidt was able to tell Postmaster Pasteur the stamps were ready and could be distributed to the public on April 1, 1845. A more dizzying speed of production cannot be found in the annals of classical stamp production.

The stamps (Scott 2L2) were printed by lithography in sheets of 100, 10 rows of 10 stamps each. There were a few differences in the design from the previous Double Geneva.

The denomination was “5 C,” and there was no dot after the “C.” The inscription “Poste de Geneve,” instead of being placed at angles over the shield, was placed in a more seemly arch. The inscription “JHC” was replaced by “IHC,” which meant the same. The inscription below the shield now read “Port Cantonal” because the stamp was valid equally for city mail and cantonal mail. The eagle was drawn with more detail, and its wing did not touch the escutcheon’s border; more obvious yet, the bird was not crowned.

One more detail is important. This stamp’s layout on the stone left very little space between stamps. The average distance between stamps, both vertically and horizontally was about ½ millimeter; that means that a stamp with clear margins of about ¼mm on all sides may be considered to be a very fine example. The only other classic stamps that come to mind with such narrow space between subjects are those of the first issues of Thurn and Taxis.

Schmidt printed 120,000 examples of this stamp. Because the Double Geneva was still available, the post office encouraged its use, in singles, of course, as the basic rate was now 5c.

Business was picking up for the post office. In December 1846, another order was placed with the lithographers. In about 21 months, the stock of 120,000 stamps was depleted. That means about 5,700 stamps, on average, were sold each month. Compare that with 500 to 700 stamps sold in late 1844.

There is little question that the Geneva experiment worked very well. The number of letters posted had increased steadily, and the number of letters bearing postage paid had increased tenfold in less than two years. The public paid less for their postage, and businesses were entirely satisfied with their post office and its workings.

There were two more stamps printed by Schmidt Lithographers in 1846 and 1848 (Scott 2L3 and 2L4). They differ in details from the two dealt with here, and I will discuss their history and characteristics in a future column.

Images are from the archive of Sergio and Liane Sismondo.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers